nLab manifold diagram

Contents

Idea

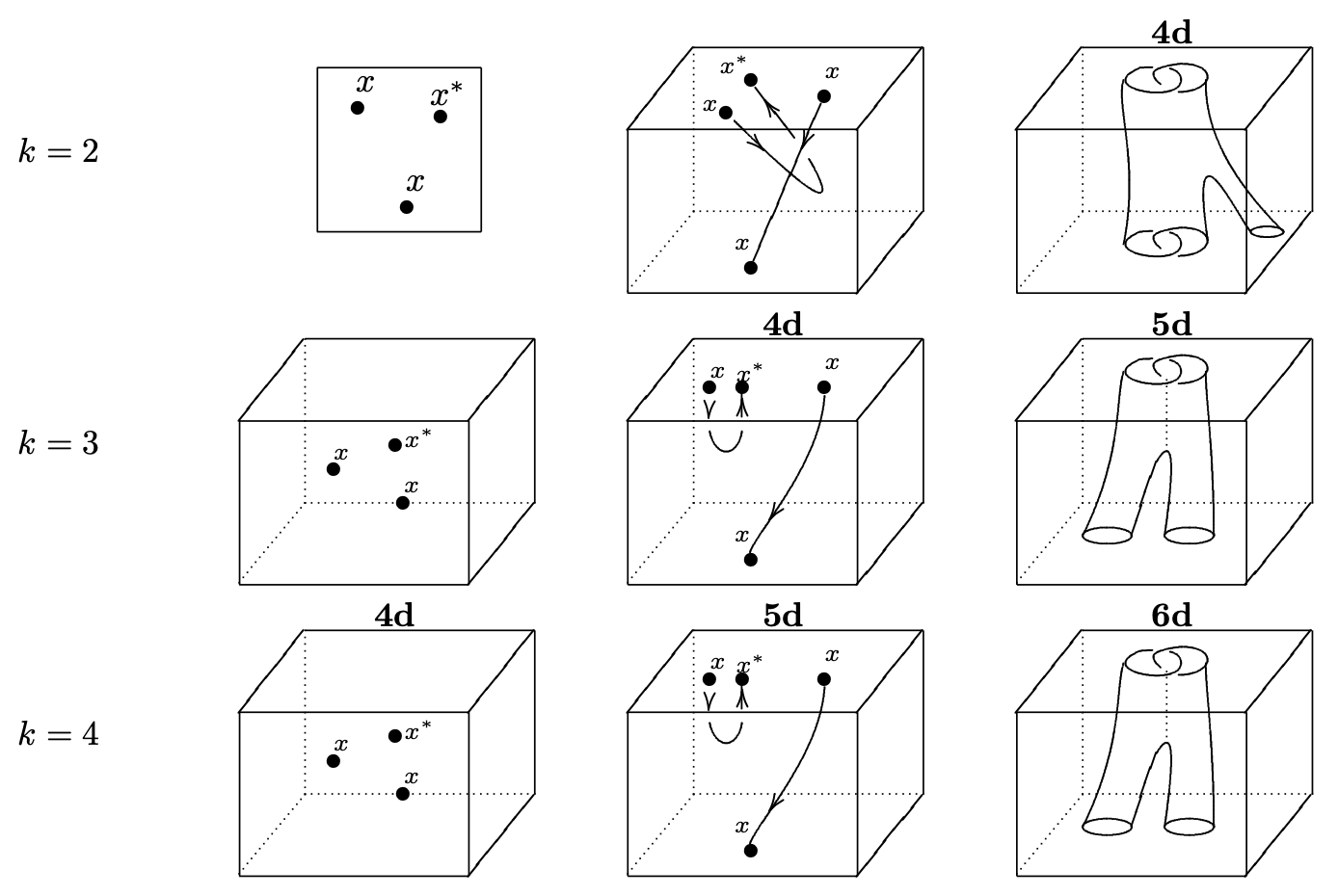

Manifold -diagrams generalize string diagrams to higher dimensions—they recover string diagrams in dimension . For , they specialize to the notion of surface diagrams.

The idea of manifold diagrams has its roots in the relation between stratified manifolds and higher categories. One way to think about this relation is by noting that stratified manifolds arise after dualizing (in the sense of Poincaré duality) pasting diagrams of directed cells in higher categories.

A well-known instance of this relation materializes in the generalized tangle hypothesis: indeed, tangles can (in a canonical way) be regarded as examples of manifold diagrams.

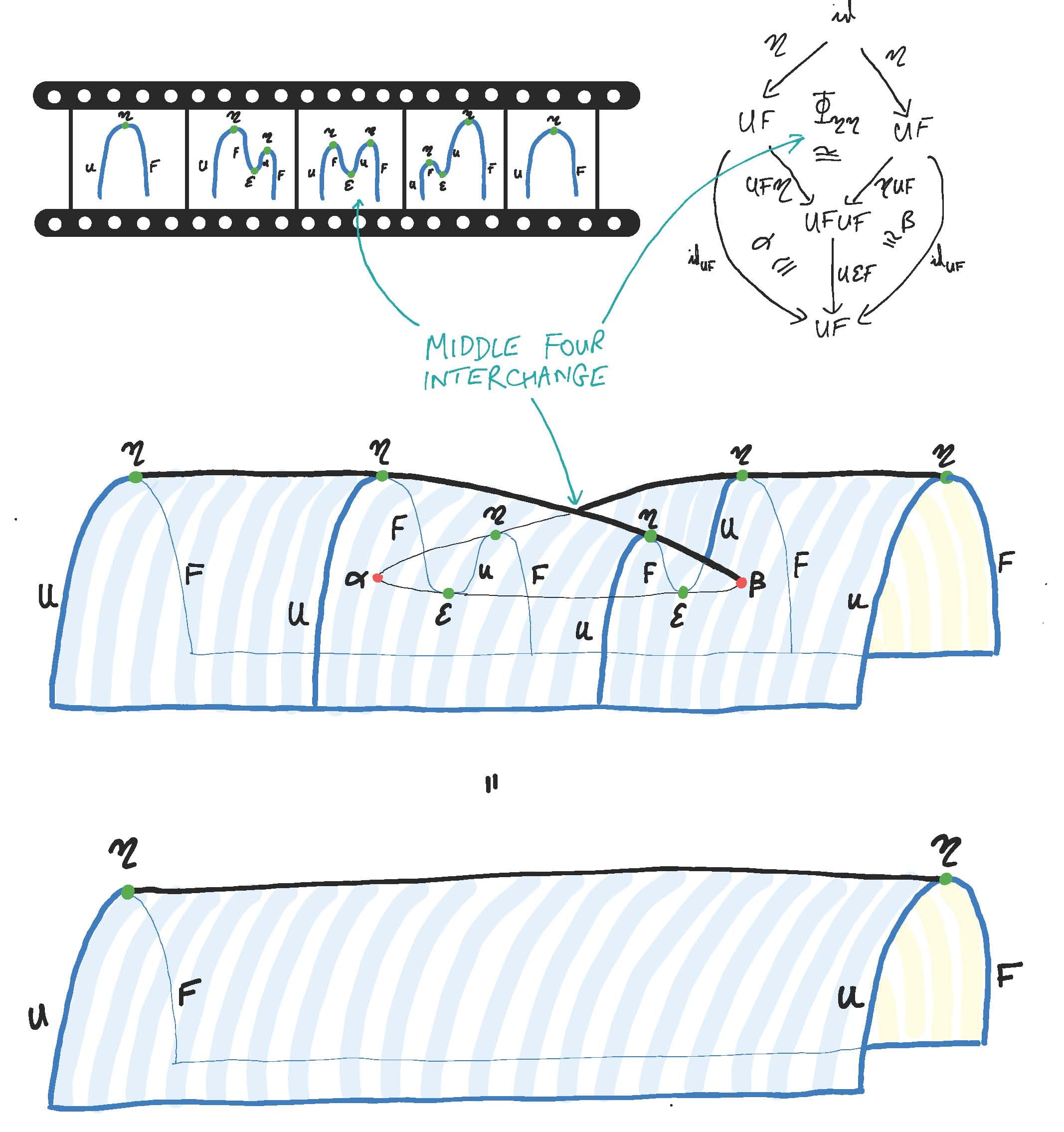

From the perspective of the tangle hypothesis, manifold diagrams can be used to express the structure of coherently dualizable objects. More precisely, this translates between “manifold singularities” and relations satisfied by the higher morphisms associated to a coherently dualizable objects. For instance, the manifold diagram in Figure 2 expresses the “swallowtail identity” satisfied by coherent biadjunctions (this is a manifold 4-diagram: think about the two surfaces as embedded in 3-dimensional space, and in the 4th spatial dimension we deform the top surface into the bottom one). The terminology derives from Thom’s classification of classical singularities (cf. this picture).

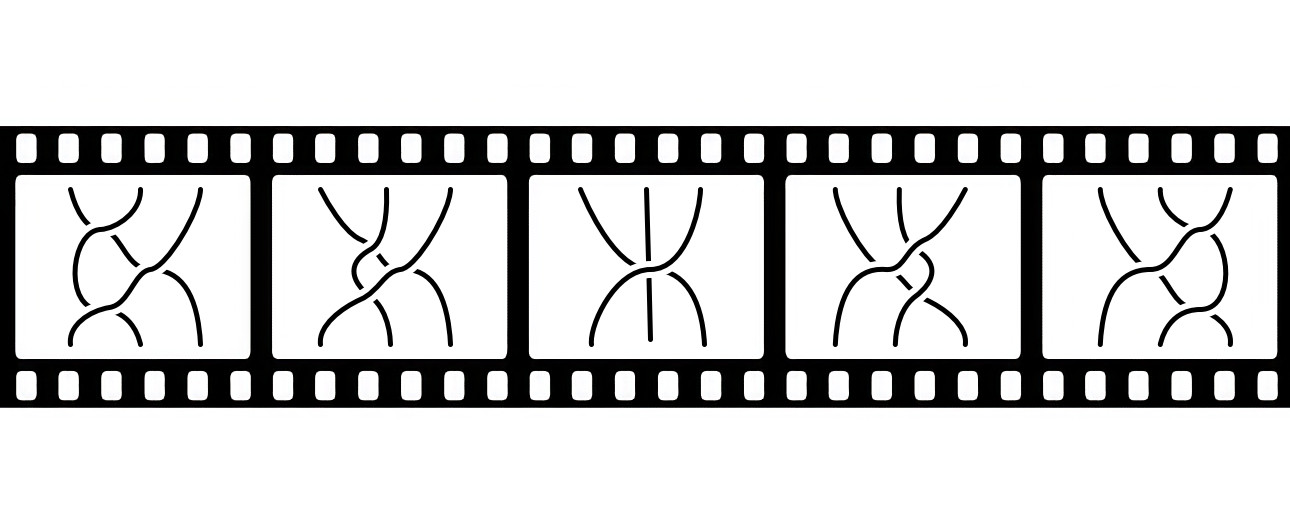

Many other interesting categorical and higher-algebraic identities can be expressed in manifold diagrams in a similar way. As an example, the Yang–Baxter equation (or, relatedly, the Reidemeister moves) can be expressed in manifold 4-diagrams as well, see Figure 3.

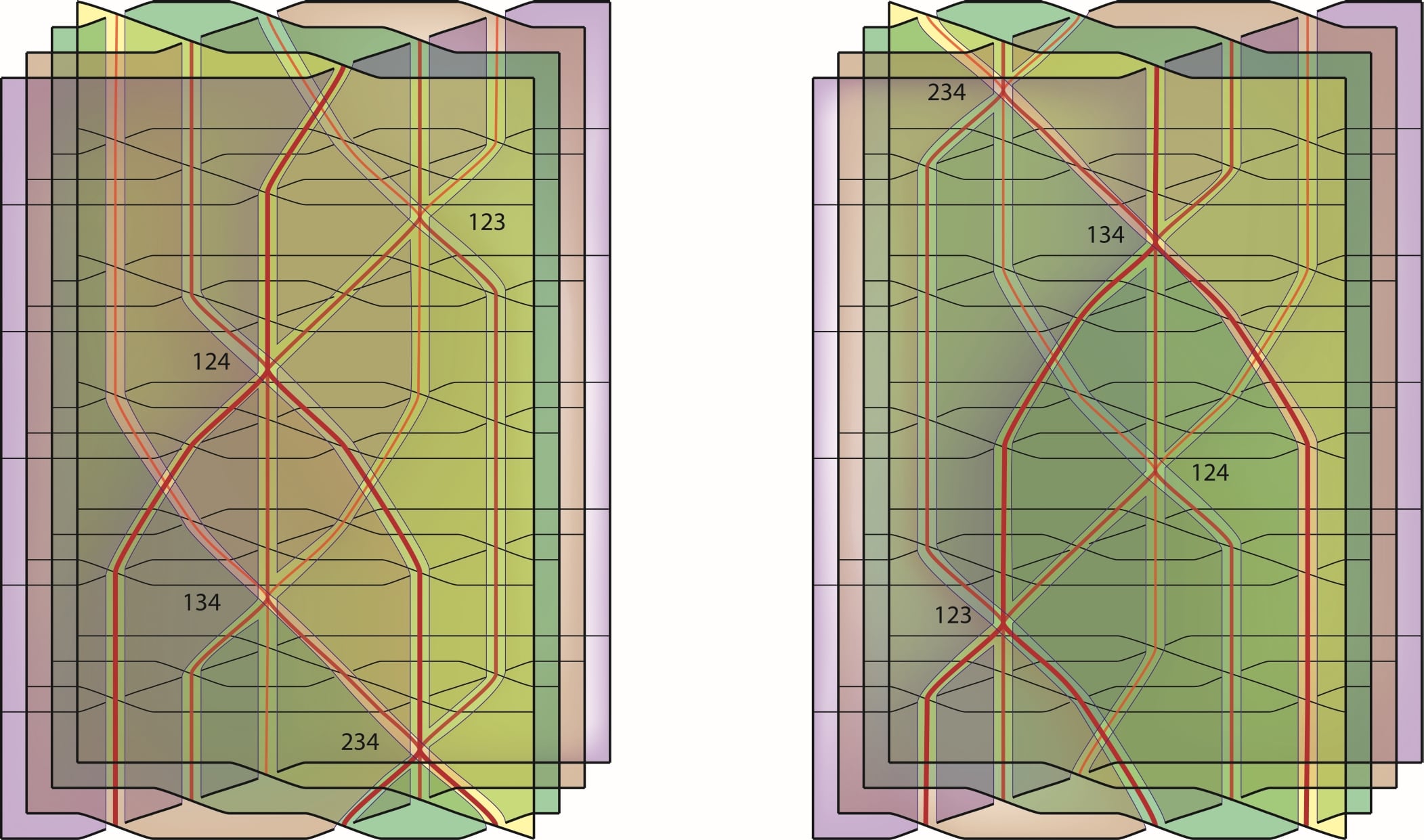

In higher dimensions the types of identites become more and more complicated: Figure 4 shows a manifold 5-diagram representing the Zamolodchikov tetrahedron equation). Much diagrammatic algebra of surfaces along these lines as been developed by Carter and collaborators.

Manifold diagrams are meant to provide a definitional framework for higher algebraic laws such as those above in all dimensions. Moreover, while the above examples only illustrate such laws for tangles (i.e. for embedded ordinary manifolds), in full generality manifold diagrams are diagrams of stratified manifolds.

Definition

Outline

Several definitional variants exist in dimensions (see also at surface diagrams). In general dimensions, manifold diagrams (introduced in Dorn-Douglas 2022) can be defined as conical, compactly triangulable stratifications of directed euclidean space.

Definition

A manifold -diagram is a conical, compactly triangulable stratification of standard -dimensional directed space.

Here, “standard directed space” can be taken to mean standard with standard -framing. The term “conical” means a directed version of usual conicality; namely, in the context of directed spaces one requires tubular neighborhoods to interact nicely with the directions of the underlying directed space. “Compact triangulability” means, roughly, that up to isomorphism a description by finite data can be given.

Details

We provide details for the preceding definition.

Definition

The standard -framing of is the chain of oriented -fiber bundles () with defined to be the map that forgets the last coordinate of (and fibers carry the standard orientation of after identifying ).

When considering we tacitly always think of it as ‘standard framed ’ and, thus, we stop mentioning the standard framing as an explicit structure all-together. Indeed, more important than defining the standard -framing is to define the maps that preserve it.

Definition

A framed map is a map for which there exist (necessarily unique) maps () with such that with preserving orientations of fibers of (i.e. mapping fibers strictly monotously).

A framed stratified map is a stratified map whose underlying map is framed. Moreover, when working with products we will identitify in the standard way; and, when working with cone stratifications , we will standard embed and identify by mapping to .

Definition

A stratification is framed conical if each point it has a framed stratified neighborhood (framed) homeomorphic to with , where and is some stratification.

Definition

A compactly-described triangulation of is a finite stratification of by open disks whose closures are the images of linear embeddings (). This now translates to the framed stratified case as follows: a stratification is framed compactly triangulable if it admits a framed stratified subdivision of by a compactly-described triangulation .

We can now put these concepts together to obtain the following form definition of manifold diagrams.

Definition

(Formalization of earlier sketch). A manifold -diagram is a framed conical, framed compactly triangulable stratification of .

The natural ‘isomorphism’ relation of manifold diagrams is framed stratified homeomorphism.

Properties

The definition has several important consequences, which we list in this section. These consequences have been formally worked out in Dorn and Douglas 22. (Note the primary definition in the latter text differs from that given here, but a comparison is given.)

Combinatorialization theorem

While the compact triangulability condition requires the existence of some combinatorial representation, there is in fact a canonical combinatorial representation for isomorphism classes of manifold diagrams. This leads to a theory of combinatorial objects called trusses. The full ‘combinatorialization theorem’ is spelled out here.

Framed smooth structure of strata

Strata in manifold diagrams are, indeed, manifolds. Moreover, they have canonical smooth structures. This follows since manifold strata carry canonical PL structure, and are canonically framed, and since framed PL manifolds have unique compatible framed smooth structure.

Well-definedness of links

Links of tubular neighborhoods in manifold diagrams are in fact well-defined. That is, there is, up to isomorphism, a unique choice of link. This stands in contrast to classical topological conical stratifications, where non-homeomorphic choices of links exist.

Dual cellular theory of manifold diagrams

Manifold diagrams have canonical geometric duals (in the sense of Poincaré duality). This relates manifold diagrams to ‘diagrams of directed cells’ in the sense of classical pasting diagrams (but with cell shapes that generalize many common classes of shapes such as ‘globular’, ‘simplicial’, or ‘opetopic’ shapes). Details are spelled out in Dorn and Douglas 22, Sec. 2.4.

Related concepts

References

-

John Baez and James Dolan, Higher-dimensional Algebra and Topological Quantum Field Theory, 1995 (arXiv)

-

Scott Carter, An excursion in diagrammatic algebra, 2012, World Scientific (doi:10.1142/8315)

-

Christoph Dorn and Christopher Douglas, Manifold diagrams and tame tangles, 2022 (arXiv, latest)

-

Christoph Dorn, Nine short stories about geometric higher categories, 2023 (pdf)

Brief introductions:

-

From zero to manifold diagrams, TallCat Seminar Talk, (video)

-

An Invitation to Geometric Higher Categories, -Category Café post

-

Christoph Dorn, Manifold Diagrams – A Brief Report, talk at CQTS (15 Nov 2023) [pdf, YT]

Last revised on November 18, 2023 at 13:04:36. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.