nLab Cauchy principal value

Context

Integration theory

Analytic integration

Riemann integration, Lebesgue integration

line integral/contour integration

integration of differential forms

integration over supermanifolds, Berezin integral, fermionic path integral

Kontsevich integral, Selberg integral, elliptic Selberg integral

Cohomological integration

integration in ordinary differential cohomology

integration in differential K-theory

Variants

Functional analysis

Overview diagrams

Basic concepts

Theorems

Topics in Functional Analysis

Contents

Idea

The Cauchy principal value of a function which is integrable on the complement of one point is, if it exists, the limit of the integrals of the function over subsets in the complement of this point as these integration domains tend to that point symmetrically from all sides.

One also subsumes the case that the “point” is “at infinity”, hence that the function is integrable over every bounded domain. In this case the Cauchy principal value is the limit, if it exists, of the integrals of the function over bounded domains, as their bounds tend symmetrically to infinity.

The operation of sending a compactly supported smooth function (bump function) to Cauchy principal value of its pointwise product with a function that may be singular at the origin defines a distribution, usually denoted .

When the Cauchy principal value exists but the full integral does not (hence when the full integral “diverges”) one may think of the Cauchy principal value as “exracting a finite value from a diverging quantity”. This is similar to the intuition of the early days of renormalization in perturbative quantum field theory (Schwinger-Tomonaga-Feynman-Dyson), but one has to be careful not to carry this analogy too far.

One point where the Cauchy principal value really does play a key role in perturbative quantum field theory is in the computation of Green functions (propagators) for the Klein-Gordon operator and the Dirac operator. See remark below and see at Feynman propagator for more on this.

Definition

As an integral

Definition

(Cauchy principal value of an integral over the real line)

Let be a function on the real line such that for every positive real number its restriction to is integrable. Then the Cauchy principal value of is, if it exists, the limit

As a distribution

Definition

(Cauchy principal value as distribution on the real line)

Let be a function on the real line such that for all bump functions the Cauchy principal value of the pointwise product function exists, in the sense of def. . Then this assignment

defines a distribution .

Examples

The principal value of

Example

Let be an integrable function which is symmetric, in that for all . Then the principal value integral (def. ) of exists and is zero:

This is because, by the symmetry of and the skew-symmetry of , the two contributions to the integral are equal up to a sign:

Example

The principal value distribution (def. ) solves the distributional equation

Since the delta distribution solves the equation

we have that more generally every linear combination of the form

for , is a distributional solution to .

The wave front set of these solutions is

Proof

The first statement is immediate from the definition: For any bump function we have that

Regarding the second statement: One computes that the Fourier transforms (with oscillation factor and normalization factor 1) of and are given by and , respectively. From this the statement immediately follows.

This follows by the characterization of extension of distributions to a point, see there at this prop. (Hörmander 90, thm. 3.2.4)

Definition

(integration against inverse variable with imaginary offset)

Write

for the distribution which is the limit in of the non-singular distributions which are given by the smooth functions as the positive real number tends to zero:

hence the distribution which sends to

Proposition

(Cauchy principal value equals integration with imaginary offset plus delta distribution)

The Cauchy principal value distribution (def. ) is equal to the sum of the integration over with imaginary offset (def. ) and a delta distribution.

(Plemelj-Sochocki formula)

In particular, by prop. this means that solves the distributional equation

Proof

Using that

we have for every bump function

Since

it is plausible that , and similarly that . In detail:

and

where we used that the derivative of the arctan function is and that is proportional to the sign function.

Example

(Fourier integral formula for step function)

The Heaviside distribution is equivalently the following Cauchy principal value:

where the limit is taken over sequences of positive real numbers tending to zero.

Proof

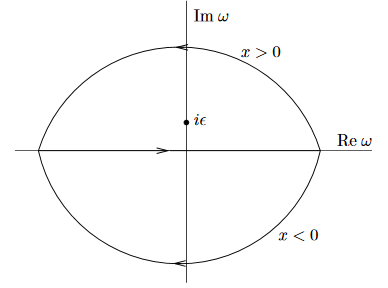

We may think of the integrand uniquely extended to a holomorphic function on the complex plane and consider computing the given real line integral for fixed as a contour integral in the complex plane.

If is positive, then the exponent

has negative real part for positive imaginary part of . This means that the line integral equals the complex contour integral over a contour closing in the upper half plane. Since has positive imaginary part by construction, this contour does encircle the pole of the integrand at . Hence by the Cauchy integral formula in the case one gets

Conversely, for the real part of the integrand decays as the negative imaginary part increases, and hence in this case the given line integral equals the contour integral for a contour closing in the lower half plane. Since the integrand has no pole in the lower half plane, in this case the Cauchy integral formula says that this integral is zero.

Conversely, by the Fourier inversion theorem, the Fourier transform of the Heaviside distribution is the Cauchy principal value as in prop. :

Example

(relation to Fourier transform of Heaviside distribution / Schwinger parameterization)

Here the second equality is also known as complex Schwinger parameterization.

Proof

As generalized functions consider the limit with a decaying component:

The principal value of

Let be a non-degenerate real quadratic form analytically continued to a real quadratic form

Write for the determinant of

Write for the induced quadratic form on dual vector space. Notice that (and hence ) are assumed non-degenerate but need not necessarily be positive or negative definite.

Proposition

(Fourier transform of principal value of power of quadratic form)

Let be any real number, and any complex number. Then the Fourier transform of distributions of is

where

-

deotes the Gamma function

-

denotes the modified Bessel function.

Notice that diverges for as (DLMF 10.30.2).

(Gel’fand-Shilov 66, III 2.8 (8) and (9), p 289)

Example

Let be the dual Minkowski metric in dimension . Then

is the Feynman propagator for the Klein-Gordon equation on Minkowski spacetime. In this case prop. implies that its singular support is the light cone .

The Fourier transform of

Let be a non-degenerate real quadratic form analytically continued to a real quadratic form

Write for the determinant of . Write for the number of negative eigenvalues.

Write for the induced quadratic form on dual vector space. Notice that (and hence ) are assumed non-degenerate but need not necessarily be positive or negative definite.

Proposition

(Fourier transform of delta distribution applied to mass shell)

Let , then the Fourier transform of distributions of the delta distribution applied to the “mass shell” is

where denotes the modified Bessel function of order .

Notice that diverges for as (DLMF 10.30.2).

(Gel’fand-Shilov 66, III 2.11 (7), p 294)

Example

Let be the dual Minkowski metric in dimension . Then

is the causal propagator for the Klein-Gordon equation on Minkowski spacetime. In this case prop. implies that its singular support is the light cone .

Related concepts

References

Named after Augustin Cauchy

- Ram Kanwal, section 8.3 of Linear Integral Equations Birkhäuser 1997

Detailed discussion of relation to Bessel functions is in

- I. M. Gel'fand, G. E. Shilov, Generalized functions, 1–5 , Acad. Press (1966–1968) transl. from И. М. Гельфанд, Г. Е. Шилов Обобщенные функции, вып. 1-3, М.:Физматгиз, 1958; 1: Обобщенные функции и действия над ними, 2: Пространства основных обобщенных функций, 3: Некоторые вопросы теории дифференциальных уравнений

References on homogeneous distributions

- Lars Hörmander, The Analysis of Linear Partial Differential Operators I (Springer, 1990, 2nd ed.)

See also

-

Wikipedia, Cauchy principal value

-

Wikipedia, Hadamard principal value

Last revised on September 29, 2023 at 06:20:24. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.