nLab lens (in computer science)

Context

Computation

constructive mathematics, realizability, computability

propositions as types, proofs as programs, computational trinitarianism

Constructive mathematics

Realizability

Computability

Contents

Idea

In computer science, originally in database theory, a data structure-type now called (lawful) lenses [Bohannon, Pierce & Vaughan (2006, §3), Foster, Greenwald, Moore, Pierce & Schmitt (2007, §3), but considered under different names already by Oles 1982, 1986 and Hofmann & Pierce 1996] is used to encode data(-base) types equipped with a read/write functionality (only) for a specified view-type .

In particular, “very well-behaved” or “lawful” lenses (see Def. below) – those for which updates of the “view” completely overwrite any previous such changes – turn out to equivalently be data base types of product form with “view” given by projecting onto the -factor. As such, lawful lenses are equivalent to (cf. monads in computer science):

-

the modales over the -possibility-monad

(Johnson, Rosebrugh & Wood 2010, Prop. 9, see Prop. below)

-

the comodales over the costate comonad,

(O’Connor (2010), (2011), see Prop. below).

Thus, lawful lenses may be thought of as encoding read/write functionality (only) at a certain address in a data base (compare the RAM-model given by the state monad which encodes read/write of the entire data base type at once).

More generally, there are two different approaches to lenses:

-

Lawful lenses (as above) are an algebraic structure which axiomatize product projections. The laws govern the ways views and updates relate. These are generalized into Delta lenses, which are more flexible lawful lenses.

-

Lawless lenses, and in particular bi-directional or polymorphic lenses, separate the two directions of view and update so that the laws no longer type-check. These lawless lenses are used to organize bi-directional flow of data, and are generalized into optics in the functional programming literature.

An alternate generalization of lawless lenses is put forward in Spivak 19 as the Grothendieck construction of the fiberwise dual of an indexed category. This notion of lawless lens has been adopted in the context of categorical systems theory because they represent a bidirectional stateful computation which describes the way some systems expose and update their internal state. For instance, see Myers, Spivak & Niu or Hedges (2021).

In this sense, lawless lenses are applications of two mathematical frameworks which are interesting in their own right: fibrations and optics (thus Tambara modules).

Definition

Definition

(lenses)

Given a category with finite products, a lens in is:

-

-

(“source”)

-

(“view”)

-

-

a pair of morphisms of the form

-

(“view”, “read-out”, “forward operation”)

-

(“update”, “write”, “backward operation”)

-

The lens is called well-behaved if this data satisfies:

-

(PutGet) “what has just been written is read out as such”:

and

-

(GetPut) “writing what has just been read out means no change”:

and it is called very well-behaved or lawful if in addition it satisfies:

-

(PutPut) “writing means to over-write previous edits”:

Definition appears, under no particular name, in Hofmann & Pierce 1996, p. 12, where it is thought of as providing aspects of object-oriented programming: Here one thinks of as a “class” which inherits functionality from the class . And indeed, for lawful lenses it follows (see below) that is a “record” which inherits all fields present in but may add some more).

The terminology “lens” for Def. is due to Bohannon, Pierce & Vaughan 2006, Def. 3.2.

The category of lenses

Lenses (regardless of their lawfulness) organize in a category whose objects are the same as and whose morphisms are lenses with states and views . The identity lens is given by . Composition of and is given by:

The morphism is probably easier to describe using generalized elements:

Remark

Crucially, associativity of this composition relies on naturality of the diagonals, which is a given in cartesian categories but not in more general monoidal categories. Optics are a sweeping generalization of lenses which overcomes this obstacle.

Moreover, the cartesian product of endows of a monoidal product.

Properties

Monadicity over Possibility monad

Proposition

(lawful lenses are possibility modales)

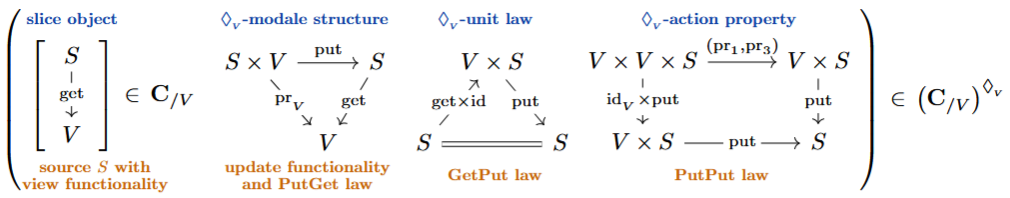

Lawful lenses in with view (Def. ) are equivalently the modules (modales) of the left base change monad on the slice category over (the -possibility-modality ):

where

-

is identified with the slicing morphism,

-

is identified with the module action .

Proof

By direct unwinding of the definitions:

Proposition

If the ambient category is a topos (such as Sets) and the view is inhabited, then the adjunction (1) is monadic.

Proof

The monadicity theorem (here) readily gives that the above adjunction (1) is monadic functor: preserves all colimits (cf. universal colimits) hence in particular the relevant coequalizers, and it is conservative by the assumption that is inhabited (this is clear by inspection in Sets – which is what JRW10 observe on their p. 13 – for the general case use Johnstone 2002, vol 1, Lem. 1.3.2).

Remark

(relation to monadic descent)

In (algebraic) geometry, the statement of Prop. is known as monadic descent. In this context one would say that:

-

the epimorphism (reflecting that is inhabited, necessarily an effective epimorphism given that is assumed to be a topos) is the morphism of effective descent, representing a covering,

-

-modale-structure is descent data on the underlying object in ,

-

the EM-category is the category of descent data along ,

and so the monadicity theorem in Prop. states that objects over which are equipped with such descent data are equivalent to objects over , hence “do descend” along .

Remark

(relation to epistemic logic)

Prop. says that the category of -modales among objects in is equivalent to . This makes good sense when viewing as the possibility-modality, see the discussion of potentiality there.

Monadicity over the CoState comonad

Alternatively:

Proposition

(lawful lenses are the costate coalgebras)

For a cartesian closed category, the lawful -lenses in (Def. ) are equivalently the coalgebras of the -CoState comonad, i.e. that induced by the internal hom-adjunction:

A proof is spelled out here at store comonad.

Generalizations

There are many generalizations of lenses which have been proposed, however they can be broadly classified into those which satisfy analogues of the lens laws, and those without any axioms or laws.

Lenses without laws

- One generalization considers the lenses from the previous section as monomorphic by contrast to polymorphic lens which go between pairs of types, , consisting of a view function, , and an update function . Without further conditions, these are known as bimorphic lenses. To impose conditions comparable to the lens laws above requires that the types be related.

These sorts of lenses are generalized by Spivak 19. For a quick explanation of how these sorts of generalized lenses are of use in systems theory, see Myers20; for a longer explanation, see Chapter 2 of Myers.

- An optic generalizes the way lenses ‘remember’ state from the forward part to the backward part, avoiding the necessity of a cartesian structure by swapping it with a sufficiently rich actegorical context.

Lenses with laws

-

Delta lenses are a generalization which does satisfy laws. Here we have categories and called the source and view, together with a Get functor and a function which takes a pair to a morphism

in where is the Put function. The function must also satisfy three lens laws. When and are codiscrete categories, delta lenses are equivalent to a lens in Set; see (Johnson-Rosebrugh 2016, Proposition 4).

-

A morphism between directed containers is another kind of generalised lens satisfying laws called update-update lenses; see (Ahman-Uustalu 2017, Section 5). These are equivalent to cofunctors.

Related entries

References

General

The definition of what are now called (lawful) lenses is already in

-

Frank J. Oles, A category-theoretic approach to the semantics of programming languages, Syracuse University (1982) [pdf]

-

Frank J. Oles, Type algebras, functor categories and block structure, Algebraic methods in semantics (1986) 543–573, Daimi Report No. 156 (1983): [doi:10.7146/dpb.v12i156.7430, pdf]

-

Martin Hofmann, Benjamin Pierce, p. 12 in: Positive Subtyping, Information and Computation 126 1 (1996) 11-33 [doi:10.1006/inco.1996.0031]

(motivated by object-oriented programming)

but gained wider attention only with:

-

Aaron Bohannon, Benjamin C. Pierce, Jeffrey A. Vaughan, Relational lenses: a language for updatable views, Proceedings of Principles of Database Systems (PODS) (2006) 338-347 [doi:10.1145/1142351.1142399, pdf]

-

J. N. Foster, M. B. Greenwald, J. T. Moore, Benjamin C. Pierce, A. Schmitt, Combinators for bidirectional tree transformations: A linguistic approach to the view-update problem, ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems 29 3 (2007) 17-es [doi:x10.1145/1232420.1232424]

Further discussion:

-

Michael Johnson, Robert Rosebrugh, Richard Wood, Algebras and Update Strategies, Journal of Universal Computer Science 16 (2010) [doi:10.3217/jucs-016-05-0729]

-

Michael Johnson, Robert Rosebrugh, and Richard J. Wood, Lenses, fibrations and universal translations Math. Structures Comput. Sci. 22 1 (2012) 25–42 [doi:10.1017/S0960129511000442]

-

Michael Johnson, Robert Rosebrugh, Unifying Set-Based, Delta-Based and Edit-Based Lenses, CEUR Workshop Proceedings 1571 (2016) [pdf]

-

Danel Ahman, Tarmo Uustalu, Taking updates seriously, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 1827, 2017 (pdf)

-

Mitchell Riley, Categories of optics [arXiv:1809.00738, video:YT]

-

David Spivak, Generalized Lens Categories via functors (arXiv:1908.02202)

-

David Jaz Myers, Double Categories of Dynamical Systems (Extended Abstract) (arXiv:2005.05956)

-

Michael Johnson, Robert Rosebrugh, The more legs the merrier: A new composition for symmetric (multi-)lenses, EPTCS 333 (2021) 92-107 [arXiv:2101.10482, doi:10.4204/EPTCS.333.7]

-

Bryce Clarke, Internal lenses as functors and cofunctors, EPTCS, 323, 2020 (doi:10.4204/EPTCS.323.13)

-

Bryce Clarke, A diagrammatic approach to symmetric lenses, EPTCS, 333, 2021 (arXiv:2101.10481)

-

Bryce Clarke, Derek Elkins, Jeremy Gibbons, Fosco Loregian, Bartosz Milewski, Emily Pillmore, Mario Román, Profunctor optics, a categorical update, (arXiv:2001.07488)

-

Matthew Di Meglio, The category of asymmetric lenses and its proxy pullbacks, Master’s Thesis, Macquarie University, (2021) [doi:10.25949/20236449.v1]

-

Matthew Di Meglio, Coequalisers under the Lens, EPTCS 372, (2022) 149-163. [doi:10.4204/EPTCS.372.11]

-

Bryce Clarke and Matthew Di Meglio, An introduction to enriched cofunctors, (2022) [arXiv:2209.01144]

-

Matthew Di Meglio, Universal Properties of Lens Proxy Pullbacks, EPTCS 380 (2023) 400-416 [doi:10.4204/EPTCS.380.23]

Relation to the costate comonad

The observation that lenses are equivalently nothing but the coalgebras of the costate comonad (cf. monads in computer science) is due to:

-

Russell O’Connor, Lenses Are Exactly the Coalgebras for the Store Comonad (30th Nov 2010) [r6research:23705]

-

Russell O'Connor, Functor is to Lens as Applicative is to Biplate: Introducing Multiplate, contribution to ICFP ‘11: ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Functional Programming (2011) [arXiv:1103.2841]

Early review:

Further details:

- Jeremy Gibbons, Michael Johnson, Relating Algebraic and Coalgebraic Descriptions of Lenses, Electronic Communications of the EASST 49 (2012) [doi:10.14279/tuj.eceasst.49.726, pdf]

Further review:

-

Bartosz Milewski, pp 240 in: The Dao of Functional Programming (2023) [pdf, github]

Relation to produoidal categories

- Craig Pastro?, Ross Street, Doubles for monoidal categories (2007)

Blog posts, talk slides, and other material

-

Jules Hedges, Lenses for philosophers (2018) [blog post]

-

David Spivak, Lenses: applications and generalizations, talk at ACT 19 (slides, pdf)

-

David Jaz Myers, Categorical systems theory, [github, pdf]

-

David Spivak, Nelson Niu, Polynomial Functors: A General Theory of Interaction [webpage, pdf]

-

Jules Hedges, Lenses as a foundation for cybernetics, CyberCat seminar, youtube

Last revised on March 23, 2024 at 10:43:04. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.