nLab homotopy theory

Context

Homotopy theory

homotopy theory, (∞,1)-category theory, homotopy type theory

flavors: stable, equivariant, rational, p-adic, proper, geometric, cohesive, directed…

models: topological, simplicial, localic, …

see also algebraic topology

Introductions

Definitions

Paths and cylinders

Homotopy groups

Basic facts

Theorems

Contents

Idea

General idea

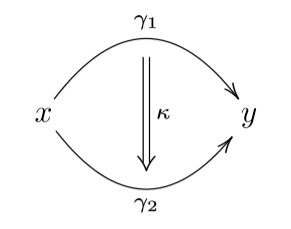

In generality, homotopy theory is the study of mathematical contexts in which functions or rather (homo-)morphisms are equipped with a concept of homotopy between them, hence with a concept of “equivalent deformations” of morphisms,

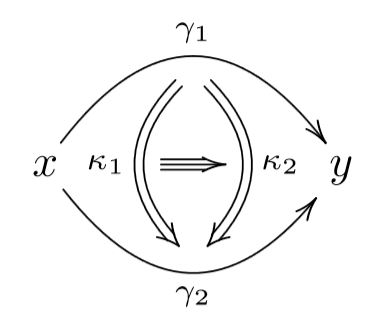

and then iteratively with homotopies of homotopies between those:

and so forth.

A key aspect here is that in such homotopy theoretic contexts the concept of isomorphism is relaxed to that of homotopy equivalence: Where a morphism is regarded as invertible if there is a reverse function such that both composites are equal to the identity morphism, for a homotopy equivalence one only requires the composites to be homotopic to the identity. Regarding objects in a homotopical context up to homotopy equivalence this way is to regard them as homotopy types.

It is not wrong to summarize this by saying that:

Homotopy theory embodies the gauge principle in mathematics.

Namely, in physics, the gauge principle says that it is wrong to ask for any two things to be equal, instead one always has to ask whether there is a gauge transformation relating them, and then a gauge-of-gauge transformation relating these, etc. Similarly in homotopy theory it is wrong to ask whether any two objects are equal, instead one has to ask whether there is a homotopy equivalence between them and then higher homotopies between these, etc.

For more exposition on the general idea of homotopy theory see:

Topological homotopy theory

The archetypical example of a homotopy theory is the classical homotopy theory of topological spaces, where one considers topological spaces with continuous functions between them, and with the original concept of topological homotopies between these continuous functions.

The category whose objects are topological spaces and whose morphisms are homotopy equivalence-classes of continuous functions is also called the classical homotopy category.

Classical constructions in topological homotopy theory are homotopy groups, Toda brackets, long exact sequences of homotopy groups, …

This classical homotopy theory of topological spaces has many applications, for example to covering space theory, to classifying space theory, to Whitehead-generalized cohomology theory and many more. (See also at shape theory.) Accordingly, homotopy theory has a large overlap with algebraic topology.

For more exposition of topological homotopy theory see:

Abstract homotopy theory

The basic structures seen in classical homotopy theory of topological spaces may be abstracted to yield an “abstract homotopy theory” that applies to a large variety of contexts. There are several more or less equivalent formalizations of the concept of “abstract homotopy theory”, including

The terminology model category is short for “category of models of homotopy types”. The idea here is to consider categories equipped with suitable extra structure and properties that encodes the existence of homotopies between all morphisms and convenient means to handle and control these, in particular a means to construct the corresponding homotopy category.

For a detailed introduction to abstract homotopy theory via model cateories see:

The approach of (∞,1)-categories to homotopy theory is meant to be more truthful to the intrinsic nature of homotopy theory. Instead of equipping an ordinary category with a extra concept of homotopy between its morphisms, here one regards the resulting structure as a higher category where the homotopies themselves appear as a kind of higher order morphisms, called 2-morphisms and where higher homotopies of homotopies are regarded as k-morphisms for all .

The terminology “(∞,1)-category” signifies that homotopy theory is but one special case of general higher category theory, namely (∞,1)-categories (hence homotopy theories) are those infinity-categories in which all k-morphisms for are invertible up to homotopy. If one drops this constraint, so that homotopies become “directed” then one might still speak of “directed homotopy theory”.

The archetypical example of an (∞,1)-category is the -category ∞Grpd of ∞-groupoids, just as Set is the archetypical 1-category.

This turns out to be equivalent, as homotopy theories, to the classical homotopy theory of topological spaces if restricted to those that admit the structure of CW-complexes.

Relation between topological and abstract homotopy theory: Cohesion.

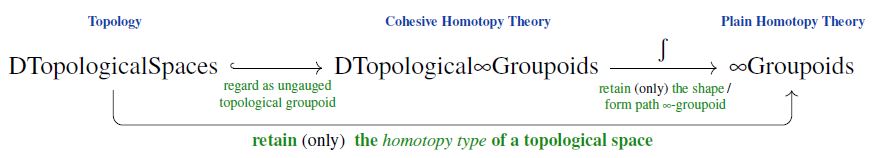

The case of the homotopy theory of topological spaces (above) is so classical that often the distinction between topology and homotopy theory has been (certainly so in the early literature) and still is often blurred (for instance in textbook titles or lecture notes). A transparent conceptual way to understand how topology and homotopy theory are closely related and yet different is provided by the notion of cohesion:

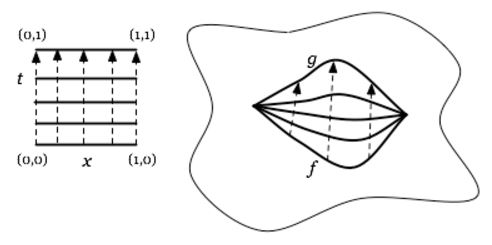

A topological space has (or presents) a homotopy type through the data that is retained in its path ∞-groupoid, conveniently modeled by its singular simplicial set (which is a Kan complex and as such an ∞-groupoid). But the topological space contains more information than that retained in its path ∞-groupoid – the latter is just a shadow of it, called the shape of the topological space.

The extra information in a topological space is the cohesion on its underlying set of points: The geometric information of how these points stick together within open subsets. This information is lost when one regards topological spaces as stand-ins for their shapes (path ∞-groupoids) in plain homotopy theory.

More formally:

The category of D-topological spaces is a full subcategory of the cohesive -topos of D-topological -groupoids (also of smooth -groupoids). These carry a qualitative aspect called their shape, which is a generalization of the fundamental ∞-groupoid-construction. Now, regarding a topological space as an object in (plain) homotopy theory, as traditionally done, really means to first regard it as a topological groupoid in cohesive homotopy theory and then, as such, to retain only its shape. The result is the homotopy type which is “presented” by the topological space:

Simplicial homotopy theory

The most immediate way to model an ∞-groupoid is as a simplicial set which is a Kan complex. Accordingly, another homotopy theory equivalent to archetypical homotopy theory of ∞-groupoids is the classical homotopy theory of simplicial sets, typically referred to as simplicial homotopy theory.

Flavors of homotopy theory

But there are many other homotopy theories besides (the various incarnations of) this classical one. Important sub-classes of homotopy theories include:

-

stable homotopy theory modeled by stable model categories and stable (∞,1)-categories, where the operations of looping and delooping are an equivalence. This includes the stable (∞,1)-category of spectra as well as those of sheaves of spectra.

-

geometric homotopy theory modeled by model toposes and (∞,1)-toposes, which are the homotopy theoretic analogs of ordinary toposes. This includes the homotopy theoretic analog of categories of sheaves, called (∞,1)-categories of (∞,1)-sheaves or of ∞-stacks, but it potentially also contains “elementary (∞,1)-toposes”.

The geometric homotopy theory of (∞,1)-toposes in particular serves as the foundation for higher geometry/derived geometry. This is relevant notably in the physics of gauge theory, where gauge transformations are identified with homotopies in geometric homotopy theory. For more on this see at geometry of physics – homotopy types.

On the other hand, the incarnation of homotopy theory as homotopy type theory exhibits the remarkably foundational nature of homotopy theory. Contrary to its original appearance as a fairly complicated-looking theory built on top of classical set theory and classical topology, homotopy theory turns out to be intrinsically simple: it arises from plain dependent type theory just by adopting a fully constructive attitude towards the concept of identity/equality, see at identity type for more on this. For exposition of this perspective see (Shulman 17).

Presentations

A convenient, powerful, and traditional way to deal with (∞,1)-categories is to “present” them by 1-categories with specified classes of morphisms called weak equivalences : a category with weak equivalences or homotopical category. The idea is as follows. Given a category with a class of weak equivalences, we can form its homotopy category or category of fractions by adjoining formal inverses to all the morphisms in . The (∞,1)-category presented by “ can be thought of as the result of regarding as an -category with only identity -cells for , then adjoining formal inverses to morphisms in in the -categorical sense; that is, making them into equivalences rather than isomorphisms. It is remarkable that most -categories that arise in mathematics can be presented in this way.

As with presentations of groups and other algebraic structures, very different presentations can give rise to equivalent -categories. For example, several different presentations of the -category of -groupoids are:

- CW-complexes, homotopy equivalences - see Quillen model structure on topological spaces

- topological spaces, weak homotopy equivalences

- Kan complexes, simplicial homotopy equivalences

- simplicial sets, weak homotopy equivalences - see Quillen model structure on simplicial sets

- small categories, functors whose nerves are weak homotopy equivalences – see Thomason model structure.

The latter three can hence be regarded as providing “combinatorial models” for the homotopy theory of topological spaces.

Model Categories

The value of working with presentations of -categories rather than the -categories themselves is that the presentations are ordinary 1-categories, and thus much simpler to work with. For instance, ordinary limits and colimits are easy to construct in the category of topological spaces, or of simplicial sets, and we can then use these to get a handle on -categorical limits and colimits in the -category of -groupoids. However, we always have to make sure that we use only 1-categorical constructions that are homotopically meaningful, which essentially means that they induce -categorical meaningful constructions in the presented -category. In particular, they must be invariant under weak equivalence.

Most presentations of -categories come with additional classes of morphisms, called fibrations and cofibrations, that are very useful in performing constructions in a homotopically meaningful way. Quillen defined a model category to be a 1-category together with classes of morphisms called weak equivalences, cofibrations, and fibrations that fit together in a very precise way (the term is meant to suggest “a category of models for a homotopy theory”). Many, perhaps most, presentations of -categories are model categories. Moreover, even when we do not have a model category, we often have classes of cofibrations and fibrations with many of the properties possessed by cofibrations and fibrations in a model category, and even when we do have a model category, there may be classes of cofibrations and fibrations, different from those in the model structure, that are useful for some purposes.

Unlike the weak equivalences, which determine the “homotopy theory” and the -category that it presents, fibrations and cofibrations should be regarded as technical tools which make working directly with the presentation easier (or possible). Whether a morphism is a fibration or cofibration has no meaning after we pass to the presented -category. In fact, every morphism is weakly equivalent to a fibration and to a cofibration. In particular, despite the common use of double-headed arrows for fibrations and hooked arrows for cofibrations, they do not correspond to -categorical epimorphisms and monomorphisms.

In a model category, a morphism which is both a fibration and a weak equivalence is called an acyclic fibration or a trivial fibration. Dually we have acyclic or trivial cofibrations. An object is called cofibrant if the map from the initial object to is a cofibration, and fibrant if the map to the terminal# object is a fibration. The axioms of a model category ensure that for every object there is an acyclic fibration where is cofibrant and an acyclic cofibration where is fibrant.

Examples

-

topological homotopy theory, classical model structure on topological spaces,

-

simplicial homotopy theory, classical model structure on simplicial sets

For a (higher) category theorist, the following examples of model categories are perhaps the most useful to keep in mind:

- sets, isomorphisms. All morphisms are both fibrations and cofibrations. The -category presented is again the 1-category .

- categories, equivalences of categories. The cofibrations are the functors which are injective on objects, and the fibrations are the isofibrations. The acyclic fibrations are the equivalences of categories which are literally surjective on objects. Every object is both fibrant and cofibrant. The -category presented is the 2-category . This is often called the folk model structure.

- (strict) 2-categories and (strict) 2-functors, 2-functors which are equivalences of bicategories. The fibrations are the 2-functors which are isofibrations on hom-categories and have an equivalence-lifting property. Every object is fibrant; the cofibrant 2-categories are those whose underlying 1-category is freely generated by some directed graph. The -category presented is the (weak) 3-category . This model structure is due to Steve Lack.

Generalized Morphisms

The morphisms from to in the -category presented by are zigzags ; these are sometimes called generalized morphisms. Many presentations (including every model category) have the property that any such morphism is equivalent to one with a single zag, as in . In a model category, a canonical form for such a zigzag is where is cofibrant and is fibrant. In this case we can moreover take to be an acyclic fibration and to be an acyclic cofibration.

Often it suffices to consider even shorter zigzags of the form or . In particular, this is the case if every object is fibrant or every object is cofibrant. For example:

- If and are strict 2-categories, then pseudofunctors are equivalent to strict 2-functors , where is a cofibrant replacement for .

- anafunctors are zigzags in the folk model structure on 1-categories whose first factor is an acyclic (i.e. surjective) fibration.

- Morita morphisms in the theory of Lie groupoids are generalized morphisms of length one where both maps are acyclic fibrations.

If is cofibrant and is fibrant, then every generalized morphism from to is equivalent to an ordinary morphism. For example, if is a cofibrant 2-category, then every pseudofunctor is equivalent to a strict 2-functor

Quillen Equivalences

Quillen also introduced a highly structured notion of equivalence between model categories, now called a Quillen equivalence, which among other things ensures that they present the same -category. Quillen equivalences are now being used to compare different definitions of higher categories.

Related entries

General

Flavors of homotopy theory

Basic concepts in homotopy theory

Categorical homotopy theory

(…)

-

Hurewicz fibration, Hurewicz connection, Hurewicz cofibration

-

model structure on simplicial sets, model structure on dendroidal sets

References

The following lists basic references on homotopy theory, algebraic topology and some -category theory and homotopy type theory, but see these entries for more pointers.

Pre-history

Historical article at the origin of all these subjects:

- Henri Poincaré, Analysis Situs, Journal de l’École Polytechnique. (2). 1: 1–123 (1895) (gallica:12148/bpt6k4337198/f7, Engl: pdf, pdf)

On early developments from there, such as the eventual understanding of the notion of higher homotopy groups:

- Peter Hilton, Subjective History of Homology and Homotopy Theory, Mathematics Magazine 61 5 (1988) 282-291 doi:10.2307/2689545

Topological homotopy theory

Textbook accounts of homotopy theory of topological spaces (i.e. via “point-set topology”):

-

Peter J. Hilton, An introduction to homotopy theory, Cambridge University Press 1953 (doi:10.1017/CBO9780511666278)

-

Sze-Tsen Hu, Homotopy Theory, Academic Press 1959 (pdf)

-

Robert E. Mosher, Martin C. Tangora, Cohomology operations and applications in homotopy theory, Harper & Row, 1968, reprinted by Dover 2008 GoogleBooks

-

Tammo tom Dieck, Klaus Heiner Kamps, Dieter Puppe, Homotopietheorie, Lecture Notes in Mathematics 157 Springer 1970 (doi:10.1007/BFb0059721)

-

Brayton Gray, Homotopy Theory: An Introduction to Algebraic Topology, Academic Press (1975) 978-0-12-296050-5, pdf

-

George W. Whitehead, Elements of Homotopy Theory, Springer 1978 (doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-6318-0)

-

Ioan Mackenzie James, General Topology and Homotopy Theory, Springer 1984 (doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8283-6)

-

Renzo A. Piccinini, Lectures on Homotopy Theory, Mathematics Studies 171, North Holland 1992 (ISBN:978-0-444-89238-6)

-

Glen Bredon, Chapter VII of: Topology and Geometry, Graduate texts in mathematics 139, Springer 1993 (doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-6848-0, pdf)

-

Hans-Joachim Baues, Homotopy types, in Ioan Mackenzie James (ed.) Handbook of Algebraic Topology, North Holland, 1995 (ISBN:9780080532981, doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-81779-2.X5000-7)

-

Nicolas Bourbaki, Topologie Algébrique, Chapitres 1 à 4, Springer (1998, 2016) [ISBN 978-3-662-49361-8, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-49361-8]

-

Marcelo Aguilar, Samuel Gitler, Carlos Prieto, Algebraic topology from a homotopical viewpoint, Springer (2008) (doi:10.1007/b97586)

-

Jeffrey Strom, Modern classical homotopy theory, Graduate Studies in Mathematics 127, American Mathematical Society (2011) [ams:gsm/127]

-

Martin Arkowitz, Introduction to Homotopy Theory, Springer (2011) [doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7329-0]

-

Anatoly Fomenko, Dmitry Fuchs: Homotopical Topology, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 273, Springer (2016) [doi:10.1007/978-3-319-23488-5, pdf]

-

Dai Tamaki, Fiber Bundles and Homotopy, World Scientific (2021) [doi:10.1142/12308]

(motivated from classifying spaces for principal bundles/fiber bundles)

Algebraic topology

Monographs:

-

Samuel Eilenberg, Norman Steenrod, Foundations of Algebraic Topology, Princeton University Press 1952 (pdf, ISBN:9780691653297)

-

Roger Godement, Topologie algébrique et theorie des faisceaux, Actualités Sci. Ind. 1252, Hermann, Paris (1958) webpage, pdf

-

Edwin Spanier, Algebraic topology, McGraw Hill (1966), Springer (1982) (doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-9322-1)

-

William S. Massey, Algebraic Topology: An Introduction, Harcourt Brace & World 1967, reprinted in: Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer 1977 (ISBN:978-0-387-90271-5)

-

Klaus Lamotke: Semisimpliziale Algebraische Topologie, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften 147, Springer (1968) [doi:10.1007/978-3-662-12988-3]

(via semisimplicial sets)

-

C. R. F. Maunder, Algebraic Topology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1970, 1980) pdf]

-

Robert Switzer, Algebraic Topology - Homotopy and Homology, Die Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften in Einzeldarstellungen, Vol. 212, Springer-Verlag, New York, N. Y., 1975 (doi:10.1007/978-3-642-61923-6)

-

P. J. Giblin: Graphs, Surfaces and Homology – An Introduction to Algebraic Topology, Chapman and Hall (1977) [doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5953-8]

-

Raoul Bott, Loring Tu, Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 82, Springer (1982) [doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-3951-0]

(focus on differential forms, differential topology)

-

James Munkres: Elements of Algebraic Topology, Addison-Wesley (1984) [ISBN:9780367091415, pdf]

-

Joseph J. Rotman, An Introduction to Algebraic Topology, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 119 (1988) doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4576-6]

-

Glen Bredon, Topology and Geometry, Graduate texts in mathematics 139, Springer 1993 (doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-6848-0, pdf)

-

Albrecht Dold, Lectures on Algebraic Topology, Springer 1995 (doi:10.1007/978-3-642-67821-9, pdf)

-

William Fulton, Algebraic Topology – A First Course, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 153, Springer (1995) [doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4180-5]

-

Peter May, A concise course in algebraic topology, University of Chicago Press 1999 (ISBN: 9780226511832, pdf)

-

Tammo tom Dieck, Topologie, De Gruyter 2000 (doi:10.1515/9783110802542)

-

Allen Hatcher, Algebraic Topology, Cambridge University Press (2002) [ISBN:9780521795401, webpage]

-

Dai Tamaki, Akira Kono, Generalized Cohomology, Translations of Mathematical Monographs, American Mathematical Society, 2006 (ISBN: 978-0-8218-3514-2)

-

Tammo tom Dieck, Algebraic topology, European Mathematical Society, Zürich (2008) (doi:10.4171/048, pdf)

-

Garth Warner: Topics in Topology and Homotopy Theory, EPrint Collection, University of Washington (2005) [hdl:1773/2641, pdf, arXiv:2007.02467]

-

Peter May, Kate Ponto, More concise algebraic topology, University of Chicago Press (2012) (ISBN:9780226511795, pdf)

-

Mahima Ranjan Adhikari: Basic Algebraic Topology and Its Applications, Springer (2016) [doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2843-1, pdf]

-

Clark Bray, Adrian Butcher, Simon Rubinstein-Salzedo: Algebraic Topology, Springer (2021) [doi:10.1007/978-3-030-70608-1, pdf]

-

Holger Kammeyer: Introduction to Algebraic Topology, Compact Textbooks in Mathematics, Birkhäuser (2022) [doi:10.1007/978-3-030-98313-0]

On constructive methods (constructive algebraic topology):

- Julio Rubio, Francis Sergeraert, Constructive Algebraic Topology, Bulletin des Sciences Mathématiques

126 5 (2002) 389-412 [doi:10.1016/S0007-4497(02)01119-3, arXiv:math/0111243]

Lecture notes:

-

Michael Hopkins (notes by Akhil Mathew), algebraic topology – Lectures (pdf)

-

Friedhelm Waldhausen, Algebraische Topologie I (pdf) , II (pdf), III (pdf) (web)

-

James F. Davis and Paul Kirk, Lecture notes in algebraic topology (pdf)

Survey of various subjects in algebraic topology:

Survey with relation to differential topology:

-

Sergei Novikov, Topology I – General survey, in: Encyclopedia of Mathematical Sciences Vol. 12, Springer 1986 (doi:10.1007/978-3-662-10579-5, pdf)

-

Jean Dieudonné, A History of Algebraic and Differential Topology, 1900 - 1960, Modern Birkhäuser Classics 2009 (ISBN:978-0-8176-4907-4)

With focus on ordinary homology, ordinary cohomology and abelian sheaf cohomology:

- Jean Gallier, Jocelyn Quaintance, Homology, Cohomology, and Sheaf Cohomology for Algebraic Topology, Algebraic Geometry, and Differential Geometry, World Scientific (2022) [doi:10.1142/12495, webpage]

Some interactive 3D demos:

- Neil Strickland, Interactive pages for Algebraic Topology, web site

Further pointers:

Abstract homotopy theory

On localization at weak equivalences to homotopy categories:

- Edgar Brown, Abstract homotopy theory, Trans. AMS 119 no. 1 (1965) (doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1965-0182970-6)

On localization via calculus of fractions:

- Pierre Gabriel, Michel Zisman, Calculus of fractions and homotopy theory, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 35. Springer, New York (1967)

On localization via model category-theory:

-

Daniel Quillen, Homotopical algebra, Lecture Notes in Mathematics 43, Berlin, New York, 1967

-

Mark Hovey, Model Categories, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, Volume 63, AMS (1999) (ISBN:978-0-8218-4361-1, doi:10.1090/surv/063, pdf, Google books)

-

Philip Hirschhorn, Model Categories and Their Localizations, AMS Math. Survey and Monographs Vol 99 (2002) (ISBN:978-0-8218-4917-0, pdf toc, pdf)

-

William G. Dwyer, Philip S. Hirschhorn, Daniel M. Kan, Jeffrey H. Smith, Homotopy Limit Functors on Model Categories and Homotopical Categories, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs 113 (2004) ISBN: 978-1-4704-1340-8, pdf

On localization (especially of categories of simplicial sheaves/simplicial presheaves) via categories of fibrant objects:

- Kenneth S. Brown, Abstract Homotopy Theory and Generalized Sheaf Cohomology, Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 186 (1973) 419-458 jstor:1996573.

See also:

-

Klaus Heiner Kamps, Tim Porter, Abstract Homotopy and Simple Homotopy Theory, World Scientific 1997 (doi:10.1142/2215, GoogleBooks)

-

Haynes Miller (ed.), Handbook of Homotopy Theory, 2019

Lecture notes:

-

William Dwyer, Homotopy theory and classifying spaces, Copenhagen, June 2008 (pdf, pdf)

-

Jesper Michael Møller, Homotopy theory for beginners, 2015 (pdf, pdf)

-

Yuri Ximenes Martins, Introduction to Abstract Homotopy Theory (arXiv:2008.05302)

Introduction, from category theory to (mostly abstract, simplicial) homotopy theory:

-

Emily Riehl, Categorical Homotopy Theory, Cambridge University Press, 2014 (pdf, doi:10.1017/CBO9781107261457)

-

Birgit Richter, From categories to homotopy theory, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics 188, Cambridge University Press 2020 (doi:10.1017/9781108855891, book webpage, pdf)

See also:

-

William Dwyer, Philip Hirschhorn, Daniel Kan, Jeff Smith, Homotopy Limit Functors on Model Categories and Homotopical Categories, volume 113 of Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, American Mathematical Society (2004) (there exists this pdf copy of what seems to be a preliminary version of this book)

-

Brian Munson, Ismar Volic, Cubical homotopy theory, Cambridge University Press, 2015 (pdf, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139343329)

(with emphasis on cubical objects such as in n-excisive functors and Goodwillie calculus)

Simplicial homotopy theory

On simplicial homotopy theory:

-

Peter May, Simplicial objects in algebraic topology, University of Chicago Press 1967 (ISBN:9780226511818, djvu, pdf)

-

Edward B. Curtis, Simplicial homotopy theory, Advances in Mathematics 6 (1971) 107–209 (doi:10.1016/0001-8708(71)90015-6, MR279808)

-

André Joyal, Myles Tierney Notes on simplicial homotopy theory, Lecture at Advanced Course on Simplicial Methods in Higher Categories, CRM 2008 (pdf)

-

André Joyal, Myles Tierney, An introduction to simplicial homotopy theory, 2009 (web, pdf)

-

Paul Goerss, Kirsten Schemmerhorn, Model categories and simplicial methods, Notes from lectures given at the University of Chicago, August 2004, in: Interactions between Homotopy Theory and Algebra, Contemporary Mathematics 436, AMS 2007 (arXiv:math.AT/0609537, doi:10.1090/conm/436)

-

Francis Sergeraert, Introduction to Combinatorial Homotopy Theory, 2008 (pdf, pdf)

-

Paul Goerss, J. F. Jardine, Section V.4 of: Simplicial homotopy theory, Progress in Mathematics, Birkhäuser (1999) Modern Birkhäuser Classics (2009) (doi:10.1007/978-3-0346-0189-4, webpage)

-

Garth Warner: Categorical Homotopy Theory, EPrint Collection, University of Washington (2012) [hdl:1773/19589, pdf, pdf]

Basic -category theory

On (∞,1)-category theory and (∞,1)-topos theory:

-

André Joyal, The theory of quasicategories and its applications lectures at Advanced Course on Simplicial Methods in Higher Categories, CRM 2008 (pdf, pdf)

-

André Joyal, Notes on Logoi, 2008 (pdf, pdf)

-

Denis-Charles Cisinski, Higher category theory and homotopical algebra (pdf)

Basic homotopy type theory

On synthetic homotopy theory in homotopy type theory:

Exposition:

-

Dan Licata: Homotopy theory in type theory (2013) pdf slides, pdf, blog entry 1, blog entry 2

-

Mike Shulman, The logic of space, in: Gabriel Catren, Mathieu Anel (eds.), New Spaces for Mathematics and Physics, Cambridge University Press (2021) 322-404 arXiv:1703.03007, doi:10.1017/9781108854429.009

Textbook accounts:

-

Univalent Foundations Project: Homotopy Type Theory – Univalent Foundations of Mathematics (2013) (webpage, pdf)

-

Egbert Rijke, Introduction to Homotopy Type Theory (2019) (web, pdf, GitHub)

For more see also at homotopy theory formalized in homotopy type theory.

Outlook

Indications of open questions and possible future directions in algebraic topology and (stable) homotopy theory:

-

Tyler Lawson, The future, Talbot lectures 2013 (pdf)

-

Problems in homotopy theory (wiki)

More regarding the sociology of the field (such as its folklore results):

- Clark Barwick, The future of homotopy theory, 2017 (pdf, pdf)

Last revised on February 1, 2024 at 07:37:46. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.