nLab adjunction

This page is about adjunctions in general 2-categories. Specifically for the common case of adjunctions in Cat see at adjoint functors. For the notion of “adjunction of a set to a field” in field theory, see field extension.

Context

2-Category theory

Definitions

Transfors between 2-categories

Morphisms in 2-categories

Structures in 2-categories

Limits in 2-categories

Structures on 2-categories

Contents

Idea

A pair of 1-morphisms in a 2-category form an adjunction if they are dual to each other (Lambek (1982), cf. here) in a precise sense.

There are two archetypical classes of examples:

-

If is a monoidal category and denotes the one-object 2-category whose single hom-category is (the delooping of ), then the notion of adjoint morphisms in coincides precisely with the notion of dual objects in , subsuming, in turn, classical examples such as dual vector spaces in the case that FinDimVect.

-

Adjunctions in the 2-category Cat of categories are adjoint functors.

-

Notice that essentially everything that makes category theory nontrivial and interesting, beyond groupoid-theory, is governed by the concept of adjoint functors. In particular universal constructions such as limits and colimits, Kan extensions, (co)ends are examples of adjunctions in Cat.

-

Similarly, for any cosmos for enrichment, adjunctions in the 2-category VCat of -enriched categories are equivalently enriched adjoint functors. Already in simple cases such truth values this subsumes classical concepts such as that of Galois connections.

-

Remarkably, even adjunctions in the homotopy 2-category of -categories are equivalent to adjoint -functors, see the examples below.

These classes of examples make adjunctions a key notion in formal category theory.

-

Finally, the notion of adjunction may usefully be thought of as a generalization of the notion of equivalence in a 2-category: an adjoint 1-morphism need not be invertible (even up to 2-isomorphism) but it does have, in a precise sense, a left inverse from below or a right inverse from above.

If an adjoint 1-morphisms happens to be a genuine equivalence in a 2-category, then the adjunction is called an adjoint equivalence.

Definition

Definition

An adjunction in a 2-category is

-

a pair of 1-morphisms

(the left adjoint)

(the right adjoint)

-

a pair of 2-morphisms

(the adjunction unit)

(the adjunction counit)

such that the following equivalent conditions hold:

- triangle identity the following diagrams commute in the hom-categories (where “” denotes whiskering):

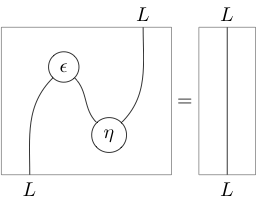

- zig-zag law the following equality of 2-morphisms:

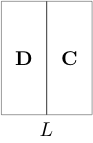

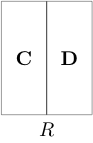

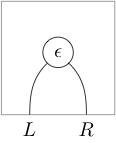

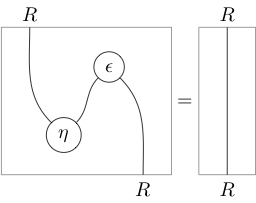

In terms of string diagrams the above data entering the definition looks like

(where 1-cells read from right to left and 2-cells from bottom to top), and the zig-zag identities appear as moves “pulling zigzags straight” (hence the name):

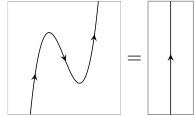

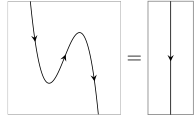

Often, arrows on strings are used to distinguish and , and most or all other labels are left implicit; so the zigzag identities, for instance, become:

Properties

Relation to monads

See at monad – Relation between adjunctions and monads.

Examples

Adjoint functors

Proposition

An adjunction in the 2-category Cat of categories, functors and natural transformations is equivalently a pair of adjoint functors.

Proof

Suppose given functors , and the structure of a pair of adjoint functors in the form of a natural isomorphism of hom-sets (here)

Now the idea is that, in the spirit of the (proof of the) Yoneda lemma, we would like to be determined by what it does to identity morphisms. With that in mind, define the adjunction unit by the formula . Dually, define the counit by the formula

Then given , the claim is that

This may be left as an exercise in the yoga of the Yoneda lemma, applied to . By formal duality, given ,

(We spell out the Yoneda-lemma proof of this dual form below.)

Finally, these operations should obviously be mutually inverse, but that can again be entirely encapsulated Yoneda-wise in terms of the effect on identity maps. Thus, if , via the recipe just given for we recover

and this is one of the famous triangle identities: . Here, juxtaposition of functors and natural transformations denotes neither functor application, nor vertical composition, nor horizontal composition, but whiskering. By duality, we have the other triangle identity . These two triangular equations are enough to guarantee that the recipes for and indeed yield mutual inverses.

In conclusion it is perfectly sufficient to define an adjoint pair of functors in as given by unit and counit transformations , , satisfying the triangle identities above.

Remark

The definition of adjunctions via units and counits is an “elementary” definition (so that by implication, the formulation in terms of hom-isomorphismsunctor#InTermsOfHomIsomorphism) is not elementary) in the sense that while the hom-functor formulation relies on some notion of hom-*set*, the formulation in terms of units and counits is purely in the first-order language of categories and makes no reference to a model of set theory. The definition via (co)units therefore gives us a definition of adjunctions even if an assumption of local smallness is not made.

Proof

(Yoneda-lemma argument)

We claim that can be defined by the formula

where . This is by appeal to the proof of the Yoneda lemma applied to the transformation

For the naturality of in the argument would imply that given , we have a commutative square

Chasing the element down and then across, we get and then . Chasing across and then down, we get and then . This completes the verification of the claim.

Corollary

An adjunction in its core 2-groupoid is an adjoint equivalence.

Enriched adjoint functors

Similarly one sees:

Example

For a cosmos for enrichment, an adjunction in the 2-category VCat of -enriched categories is equivalently a pair -enriched functors.

Example

Let from Grp to Set denote the usual forgetful functor from Grp to Set. When we say “ is the free group generated by a set ”, we mean there is a function which is universal among functions from to the underlying set of a group, which means in turn that given a function , there is a unique group homomorphism such that

Here is a component of what we call the unit of the adjunction , and the equation above is a recipe for the relationship between the map and the map in terms of the unit.

Adjoint -functors

Proposition

An adjunction in the homotopy 2-category of -categories is equivalently a pair of adjoint -functors.

Remark

In view of Prop. , the remarkable aspect of Prop. is that the homotopy 2-category of -categories is sufficient to detect adjointness of -functors, which would, a priori, be defined as a kind of higher homotopy-coherent adjointness in the full -category . For more on this reduction of homotopy-coherent adjunctions to plain adjunctions see Riehl & Verity 2016, Thm. 4.3.11, 4.4.11.

Related concepts

References

Adjunctions in 2-categories were introduced (together with the notion of strict 2-categories itself) in:

- Jean-Marie Maranda, pp. 762 in: Formal categories, Canadian Journal of Mathematics 17 (1965) 758-801 [doi:10.4153/CJM-1965-076-0, pdf]

Though see also the following, which uses more modern terminology:

- Max Kelly, §2 in: Adjunction for enriched categories, in: Reports of the Midwest Category Seminar III, Lecture Notes in Mathematics 106, Springer (1969) [doi:10.1007/BFb0059145]

A thorough 2-categorical account is contained in:

-

Claude Auderset: Adjonctions et monades au niveau des -catégories, Cahiers de topologie et géométrie différentielle 15 1 (1974) 3-20.

-

Stephen Schanuel, Ross Street: The free adjunction, Cahiers de topologie et géométrie différentielle catégoriques 27 1 (1986) 81-8

Review:

-

Saunders MacLane, §XII.4 of: Categories for the Working Mathematician, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 5 Springer (second ed. 1997) [doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4721-8]

-

Steve Lack, §2.1 in: A 2-categories companion, in: Towards Higher Categories, The IMA Volumes in Mathematics and its Applications 152 Springer (2010) [arXiv:math.CT/0702535, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1524-5_4]

-

Niles Johnson, Donald Yau, Chapter 6 of: 2-Dimensional Categories, Oxford University Press 2021 (arXiv:2002.06055, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198871378.001.0001)

Fr the special case of adjoint functors see any text on category theory (and see the references at adjoint functor), for instance:

-

Francis Borceux, Vol 1, Section 3 of Handbook of Categorical Algebra

For some early history and illustrative examples see

-

Joachim Lambek, The Influence of Heraclitus on Modern Mathematics, In Scientific Philosophy Today: Essays in Honor of Mario Bunge, edited by Joseph Agassi and Robert S Cohen, 111–21. Boston: D. Reidel Publishing Co. (1982) (doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8462-2_6)

(more along these lines at objective logic).

The fundamental role of adjoint functors in logic/type theory originates with the observaiton that substitution forms an adjoint triple with existential quantification and universal quantification:

-

William Lawvere, Adjointness in Foundations, (tac:16), Dialectica 23 (1969), 281-296

-

William Lawvere, Quantifiers and sheaves, Actes, Congrès intern, math., 1970. Tome 1, p. 329 à 334 (pdf)

Adjunctions in programming languages (though mainly again just adjoint functors):

-

Ralf Hinze, Generic Programming with Adjunctions, In: J. Gibbons (ed.) Generic and Indexed Programming Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 7470. Springer 2012 (pdf, slides doi:10.1007/978-3-642-32202-0_2)

-

Jeremy Gibbons, Fritz Henglein, Ralf Hinze, Nicolas Wu, Relational Algebra by Way of Adjunctions, Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages archive Volume 2 Issue ICFP, September 2018 Article No. 86 (pdf, doi:10.1145/3236781)

See also

-

Wikipedia, Adjoint Functors

-

Catsters, Adjunctions (YouTube)

Last revised on June 10, 2025 at 13:23:28. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.