nLab energy

this entry needs attention

Context

Physics

physics, mathematical physics, philosophy of physics

Surveys, textbooks and lecture notes

theory (physics), model (physics)

experiment, measurement, computable physics

-

-

-

Axiomatizations

-

Tools

-

Structural phenomena

-

Types of quantum field thories

-

Energy

Idea

In physics, the energy of a physical system is one of its most basic observable properties, an extensive quantity roughly measuring how much stuff is in the system.

In experiment it is often measured in units of electronvolt.

The term ‘energy’ is also used in Riemannian geometry and statistics in vague analogy with the concept from physics.

Conservation

As a system evolves? without interacting with its environment, its energy remains constant. If different systems interact, then they may exchange energy, but the total energy remains constant; equivalently, we may combine the interacting systems into a supersystem whose energy is the sum of the energies of its parts, and this supersystem’s energy is conserved.

Through Noether's theorem, conservation of energy corresponds to time invariance. If a system's equations of motion are not invariant with time, then the system will not exhibit energy conservation, and physically we conclude that the system must be interacting with something else.

In continuum physics, conservation of energy may be treated locally: the change in energy in any region over a period of time must equal the total flux of energy through the region's boundary over that time. In general relativity, this makes sense (in general) only as a differential equation involving both the stress-energy tensor and the Levi-Civita connection.

Relationship to mass

Energy is distinguished from mass in various ways:

-

Relativistic mass is the same as energy, although conventionally measured in different units. We have in conventional units, or simply in units where the speed of light is .

-

Rest mass (the usual meaning of ‘mass’ in modern physics) is the minimum energy inherent in a system; whereas energy is relative, rest mass is absolute. Here we have

(1)in conventional units, or

(2)if .

-

In the non-relativistic limit, energy splits into two independently conserved quantities: mass (relativistic or rest, it makes no difference) and energy proper. That is, expanding (1) as a power series in , we have

as , this splits into the quantities , , , etc. The first of these is the non-relativistic mass, the second is the kinetic energy , the next is simply , and all subsequent terms are also determined by and .

However, the kinetic energy is not the total energy in non-relativistic physics. Any entities with a rest mass of (or approaching zero in the limit) will still have energy and so must be treated separately from kinetic energy (which is proportional to mass). Non-relativistically, these may be viewed as fields with energy of their own, or (if the field strengths are derived entirely from interacting massive bodies) this energy may be attributed to the massive bodies in the system as potential energy. Thus the total energy of the system is , where is total kinetic energy and is total potential or field energy.

In special relativity

In relativistic physics, energy is relative, the timelike part of a 4-vector? quantity whose spacelike parts comprise linear momentum. If we also take into account the distribution of energy and momentum across space, this give a symmetric second-rank tensor, the stress-energy tensor.

Even in non-relativistic physics, there is an analogy between energy and linear momentum. In Hamiltonian mechanics, both energy and linear momentum are examples of generalised momenta; energy corresponds to time while linear momentum corresponds to position in space?. However, the special treatment accorded to time and energy in the usual formulation of Hamiltonian mechanics obscures this; we also have (oddly) that the precise generalised momentum corresponding to the time variable is not the total energy but instead.

This analogy from classical mechanics also applies to quantum mechanics and is particularly evident in Schrödinger’s original formulation of his quantum theory.

plane waves on Minkowski spacetime

In general relativity

In general relativity, the concept of total energy of a system does not make sense, except in certain special cases. General relativity is a field theory in which energy appears only as one of (or in dimensions of spacetime) independent components of the stress-energy tensor. Mathematically, it makes no sense to integrate just this component over a region of space to determine a total energy in that region. This makes it difficult to interpret general relativity in frameworks such as Hamiltonian mechanics and thermodynamics where energy is a primary concept. This is called the problem of time? (since energy and time are conjugate observables and the problem occurs with both).

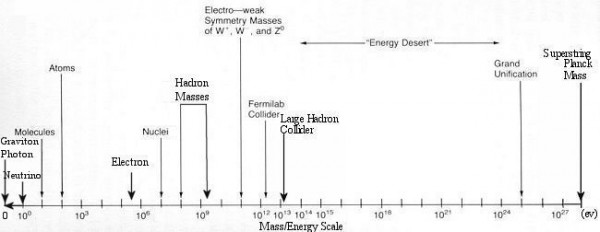

Energy scales

graphics grabbed from here

Related concepts

References

Serious references discussing energy in general relativity include

- Edward Witten, A new proof of the positive energy theorem, Comm. Math. Phys. 80 (1981), no. 3, 381–402, MR83e:83035, euclid

- A. Trautman, Conservation laws in general relativity. In: Gravitation: an introduction to current research, Witten, L. (ed.). New York: Wiley 1962;

- Misner, C., Thome, K.S., Wheeler, J.A.: Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman 1973;

- S. Weinberg, Gravitation and cosmology, New York: Wiley 1972

- R. Schoen, S. T. Yau, Comm. Math. Phys. 65 (1979), no. 1, 45–76; MR80j:83024

Last revised on September 20, 2022 at 11:41:31. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.