nLab Frobenius algebra

Context

Algebra

Algebraic theories

Algebras and modules

Higher algebras

-

symmetric monoidal (∞,1)-category of spectra

Model category presentations

Geometry on formal duals of algebras

Theorems

Frobenius algebra

- Idea

- Definition

- As associative algebra with coalgebra structure

- As associative algebra with linear form

- Further definitions

- Types of Frobenius algebras

- Commutative Frobenius algebras

- Symmetric Frobenius algebras

- Special Frobenius algebras

- †-Frobenius algebras

- Examples

- Properties

- General

- PROPs for Frobenius algebras

- Classification of 2d TQFT

- Normal form and “Spider theorem”

- Frobenius algebras in polycategories

- Related concepts

- References

Idea

A Frobenius algebra is a vector space equipped with the structures both of an algebra and of an a coalgebra in a compatible way, where the compatibility is different from (more “topological” than) that in a bialgebra/Hopf algebra:

The Frobenius property on an algebra/coalgebra states that all ways of using product operations and coproduct operations to map are equal.

More generally, Frobenius algebras can be defined internal to any monoidal category (and even in any polycategory) in which case they are sometimes called Frobenius monoids. (For example a Frobenius monoid in an endo-functor category is a Frobenius monad.)

After their original introduction in pure algebra in the 1930s, Frobenius algebras later attracted much attention for the role they play in quantum physics, in fact for two rather different roles they play there:

-

in topological quantum field theory Frobenius algebras encode the structure of 2-dimensional TQFTs:

Her the underlying vector space of the Frobenius algebra is identified (cf. functorial field theory) with the space of quantum states over a connected 1-manifold (a circle for the “closed string” states or a closed interval for the “open string” states), the product and coproduct operations are the correlators on a trinion cobordism (“pair of pants”) read in either direction, and the Frobenius property reflects the diffeomorphisms between cobordisms obtained by gluing trinions along their boundary components.

Beware that this is similar to but subtly different from the “non-compact” 2d TQFTs commonly known as the “topological string” (the A-model and the B-model of mirror symmetry-fame) which are not described by Frobenius algebras (because here one ex-cludes the “cap” cobordism and thus the trace-operation hence the finite-dimensionality on the algebra of states) but by “Calabi-Yau objects” (for more see here at TCFT.)

On the other hand, the FRS-theorem shows that all rational 2d conformal field theories – hence the compact-target-space sectors of the physical string (such as WZW models and Gepner models) – are described by Frobenius monoids internal to modular tensor categories (MTCs): Here the ambient MTC encodes the local non-topological (“chiral”) component of the conformal field theory (its spaces of conformal blocks) while the internal Frobenius monoid encodes the remaining topological “sewing constraints”.

Later

-

in quantum information theory (such as now in the ZX-calculus) Frobenius algebras encode aspects of the quantum measurement-process, including its associated wavefunction collapse (see here at quantum information theory via dagger-compact categories).

One way to understand how this comes about (not the original way, though) is to observe that in the linear type theory which is relevant for quantum information theory the reader monad and coreader comonad for a given finite set of possible measurement outcomes merge to a single Frobenius monad (the quantum reader monad, see there for more) which is in turn identified with the writer monad/cowriter comonad for a canonical Frobenius algebra structure on the linear span of .

Curiously, these two different roles that Frobenius algebras play in quantum physics are not closely related, in fact they seem somewhat orthogonal to each other.

Definition

There are a number of equivalent definitions of the concept of Frobenius algebra.

The original definition is an associative algebra with a suitable linear form on it.

In the context of 2d TQFT what crucially matters is that this is equivalent to an associative algebra structure with a compatible coalgebra structure

There are

As associative algebra with coalgebra structure

Definition

A Frobenius algebra in a monoidal category (for instance Vect with the usual tensor product of vector spaces) is

-

an object

-

-

(unit) ,

-

(counit) ,

-

(multiplication) .

-

(comultiplication) ,

-

such that:

-

is a monoid (an associative algebra when ),

-

is a comonoid (a coassociative coalgebra when ),

-

the Frobenius laws hold: .

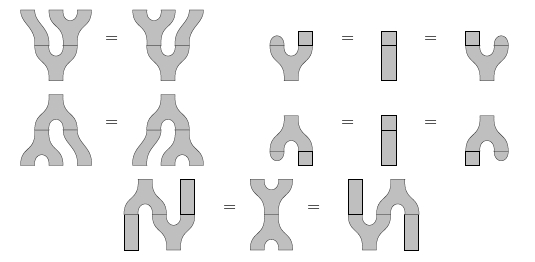

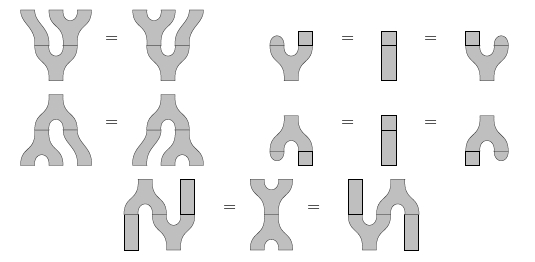

In terms of string diagrams, Def. says:

The first line here shows the associative law and left/right unit laws for a monoid. The second line shows the coassociative law and left/right counit laws for a comonoid. The third line shows the Frobenius laws.

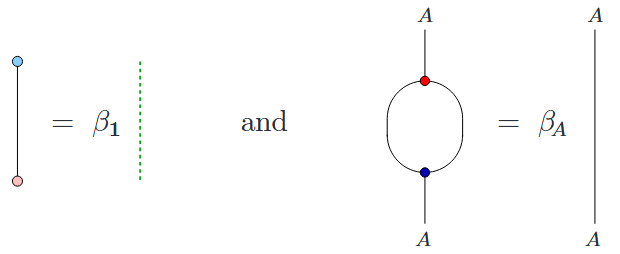

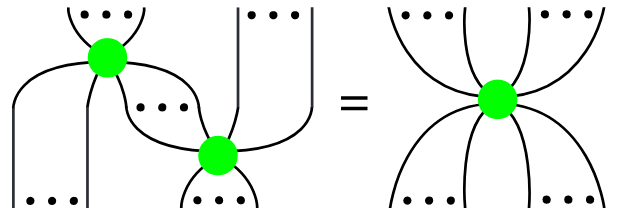

In fact, although this seems rarely to be remarked, the two Frobenius laws can be replaced by the single axiom . Here is a proof in string diagram notation that this axiom implies (taken from Pastro-Street 2008):

Here the first and fifth steps use the counitality property of the comonoid structure, the second and fourth steps use the assumed axiom (once in each direction), and the third step uses coassociativity.

As associative algebra with linear form

Frobenius algebras were originally formulated in the category Vect of vector spaces with the following equivalent definition:

Definition

A Frobenius algebra is a unital, associative algebra equipped with a linear form – to becalled a Frobenius form – such that is a non-degenerate inner product. I.e. the induced morphism

is an isomorphism of with its dual space .

From this definition it is easy to see that every Frobenius algebra in Vect is necessarily finite-dimensional.

Further definitions

There are about a dozen equivalent definitions of a Frobenius algebra. Ross Street (2004) lists most of them.

Types of Frobenius algebras

Commutative Frobenius algebras

We can define ‘commutative’ Frobenius algebras in any symmetric monoidal category. Namely, a Frobenius algebra is commutative if its associated monoid is commutative — or equivalently, if its associated comonoid is cocommutative.

Symmetric Frobenius algebras

We can define ‘commutative’ or ‘symmetric’ Frobenius algebras in any symmetric monoidal category. A Frobenius algebra is symmetric if

where is the symmetry, and is the nondegenerate pairing induced as above from the multiplication and the counit. Any commutative Frobenius algebra is symmetric, but not conversely: for example the algebra of matrices with entries in a field, with its usual trace as , is symmetric but not commutative when .

A theorem of Eilenberg & Nakayama (1955) says that in the category Vect of vector spaces over a field , an algebra can be equipped with the structure of a symmetric Frobenius algebra if (but not only if) it is separable, meaning that for any field extending , is a semisimple algebra over .

Special Frobenius algebras

Definition

The term “special Frobenius algebra” is not used consistently in the literature, but the main point is to require that the product is the left inverse to the coproduct, possibly up to a non-vanishing element in the ground field:

This condition removes the genus-contribution in normal forms of “connected maps”, up to rescaling, see below.

But then it is natural to also require the counit to be left inverse to the unit, up to (another) non-vanishing ground field element :

which also removes the disconnected “vaccum”-contribution, up to scaling.

The two conditions (1) and (2) on a Frobenius algebra are taken to be the definition of “special Frobenius” in Fuchs, Runkel & Schweigert 2002, Def. 3.4 (i):

However, other authors take the condition for “special Frobenius” to be the single constraint that

(eg. Coecke & Pavlović 2008, p. 17, Fauser 2012, Def. 3.7)

and may instead call (1) the condition to be trivially connected.

Beware that both of these conventions are adhered to by no small number of authors.

In the category of vector spaces, any element of an associative unital algebra gives a left multiplication map

which in turn gives a bilinear pairing defined by

One can show that the algebra can be equipped with the structure of a special Frobenius algebra if and only if is nondegenerate, i.e., if there is an isomorphism given by

In this case, there is just one way to make into a special Frobenius algebra, namely by taking the counit to be

(In any Frobenius algebra, the unit, multiplication and counit determine the comultiplication.)

In fact, all the results of the previous paragraph generalize to Frobenius algebras in any symmetric monoidal category, since the proofs can be done using string diagrams.

An associative unital algebra for which the bilinear pairing is nondegenerate is called strongly separable. So, any strongly separable algebra becomes a special Frobenius algebra in a unique way. For more details, see separable algebra and Aguiar (2000).

To get a feeling for some of the concepts we are discussing, an example is helpful. The group algebra of a finite group is always separable but strongly separable if and only if the order of is invertible in the field . By the results mentioned, this means that can always be made into a symmetric Frobenius algebra, but only into a special Frobenius algebra when is invertible in .

To see this, we can check that the group algebra becomes a symmetric Frobenius algebra if we define the counit to pick out the coefficient of :

But when is invertible in , we can check that becomes a special symmetric Frobenius algebra if we normalize the counit as follows:

We should warn the reader that Rosebrugh et al (2005) call a special Frobenius algebra ‘separable’. This usage conflicts with the standard definition of a separable algebra in the category of vector spaces over a field, so we suggest avoiding it.

†-Frobenius algebras

If a Frobenius algebra lives in a monoidal †-category, and , then it is said to be a †-Frobenius algebra. These crop up in the theory of 2d TQFTs, and also in the foundations of quantum theory.

Examples

Example

For FiniteSets, the -fold direct sum of the ground field – with its inherited direct sum-associative algebra-structure – becomes a Frobenius algebra by taking the

In components, if we choose the canonical linear basis

then on basis vectors these structure maps are expressed as follows (where “” is the Kronecker delta):

In these components, the Frobenius property is this equation:

Elementary as this example may be, it embdies some important principles:

For the complex numbers, the corresponding Frobenius monad (or rather ) has been proposed [Coecke & Pavlović 2008] to reflect aspects of quantum measurement in the context of quantum information via dagger-compact categories and is used as such in the zxCalculus (where the Frobenius property is embodied by “spider diagrams”). Various authors discuss the Frobenius algebras in this context, see the references there.

From another perspective on the same phenomenon (discussed at quantum circuits via dependent linear types): The -writer monad underlying the Frobenius monad is a linear version of the reader monad, as such discussed at quantum reader monad. Regarded as a computational effect its Kleisli morphisms encode quantum gates with an “indefiniteness”-effect (in the sense of quantum modal logic) whose “handling” is the process of quantum measurement.

In particular, the algebras (hence also the corresponding coalgebras) over the -dependent -linear types, namely the -vector bundles over , hence the -indexed sets of -vector spaces, understood as residual spaces of quantum states after collapse following the measurement result .

Properties

General

Proposition

A Frobenius algebra in a monoidal category is an object dual to itself.

Proof

Let be the monoidal unit. To say is dual to itself means there are maps and such that the triangle identities hold. The maps are defined by

and one of the triangle identities uses one of the Frobenius laws and unit and counit axioms to derive the following commutative diagram:

The other triangle identity uses the other Frobenius law and unit and counit axioms.

As a result, we see that in the monoidal category of modules over a commutative ring , Frobenius algebras considered as modules over are finitely generated and projective. This is because , being adjoint to itself, is a left adjoint and therefore preserves all colimits. That preserves arbitrary small coproducts means is finitely generated over , and that preserves coequalizers means is projective over .

-

Every Frobenius algebra is a quasi-Frobenius algebra: projective and injective left (right) modules over coincide.

-

Every Frobenius algebra is a pseudo-Frobenius algebra?: is an injective cogenerator in the category of left (right) -modules.

Frobenius algebras are closely connected with ambidextrous adjunctions. For example, a Frobenius monad on a category is by definition a Frobenius monoid in the monoidal category of endofunctors on (with monoidal product given by endofunctor composition), and if we have a pair of adjunctions and , then carries a monad structure and a comonad structure and the Frobenius laws are satisfied, a fact most easily seen by using string diagrams.

PROPs for Frobenius algebras

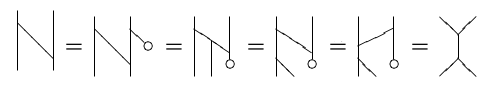

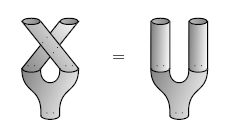

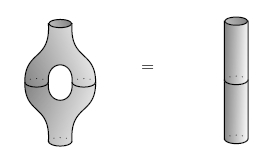

Certain kinds of Frobenius algebras have nice PROPs or PROs. The PRO for Frobenius algebras is the monoidal category of planar thick tangles, as noted by Lauda (2006) and illustrated here:

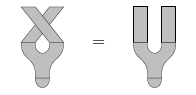

Lauda and Pfeiffer Lauda (2008) showed that the PROP for symmetric Frobenius algebras is the category of ‘topological open strings’, since it obeys this extra axiom:

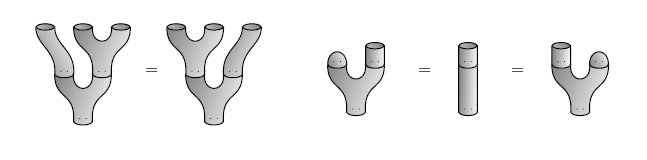

The PROP for commutative Frobenius algebras is 2Cob?, as noted by many people and formally proved in Abrams (1996). This means that any commutative Frobenius algebra gives a 2d TQFT. See Kock (2006) for a history of this subject and Kock (2004) for a detailed introduction. In 2Cob, the circle is a Frobenius algebra. The monoid laws look like this:

The comonoid laws look like this:

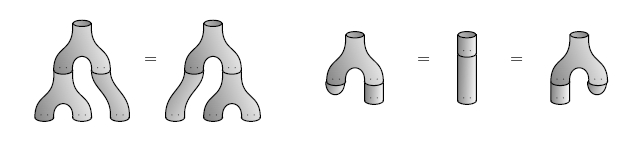

The Frobenius laws look like this:

and the commutative law looks like this:

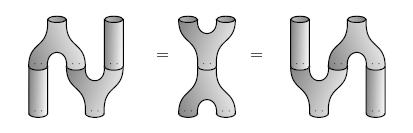

The PROP for special commutative Frobenius algebras is Cospan(FinSet), as proved by Rosebrugh, Sabadini and Walters. This is worth comparing to the PROP for commutative bialgebras, which is Span(FinSet). For details, see Rosebrugh et al (2005), and also Lack (2004).

A special commutative Frobenius algebra gives a 2d TQFT that is insensitive to the genus of a 2-manifold, since in terms of pictures, the ‘specialness’ axioms says that

Classification of 2d TQFT

| 2d TQFT (“TCFT”) | coefficients | algebra structure on space of quantum states | |

|---|---|---|---|

| open topological string | Vect | Frobenius algebra | folklore+(Abrams 96) |

| open topological string with closed string bulk theory | Vect | Frobenius algebra with trace map and Cardy condition | (Lazaroiu 00, Moore-Segal 02) |

| non-compact open topological string | Ch(Vect) | Calabi-Yau A-∞ algebra | (Kontsevich 95, Costello 04) |

| non-compact open topological string with various D-branes | Ch(Vect) | Calabi-Yau A-∞ category | “ |

| non-compact open topological string with various D-branes and with closed string bulk sector | Ch(Vect) | Calabi-Yau A-∞ category with Hochschild cohomology | “ |

| local closed topological string | 2Mod(Vect) over field | separable symmetric Frobenius algebras | (SchommerPries 11) |

| non-compact local closed topological string | 2Mod(Ch(Vect)) | Calabi-Yau A-∞ algebra | (Lurie 09, section 4.2) |

| non-compact local closed topological string | 2Mod for a symmetric monoidal (∞,1)-category | Calabi-Yau object in | (Lurie 09, section 4.2) |

Normal form and “Spider theorem”

Proposition

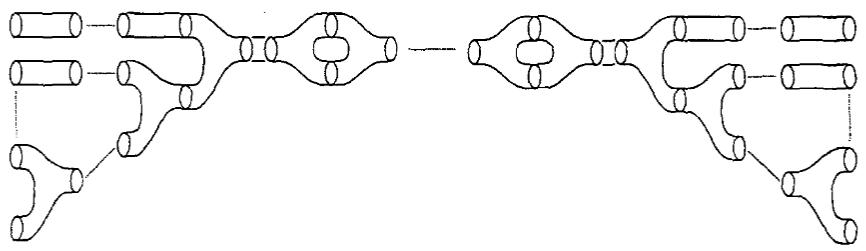

(normal form for 2d cobordisms)

Every connected cobordism with

-

ingoing boundary components

-

outgoing boundary components

is equivalent (diffeomorphic) to the composition of

as shown in the following example for

By the relation between 2d cobordism and Frobenius algebras this means equivalently that:

Corollary

(normal form for Frobenius maps)

Given a Frobenius algebra

then every linear map of the form

which is

-

entirely the composite of the algebra’s structure maps, ie. of the (co)unit and the (co)product,

-

connected, in that it does not decompose as a tensor product of such morphisms,

is equal to the composite, in this order, of

-

copies of

-

some number () of copies of

-

copies of .

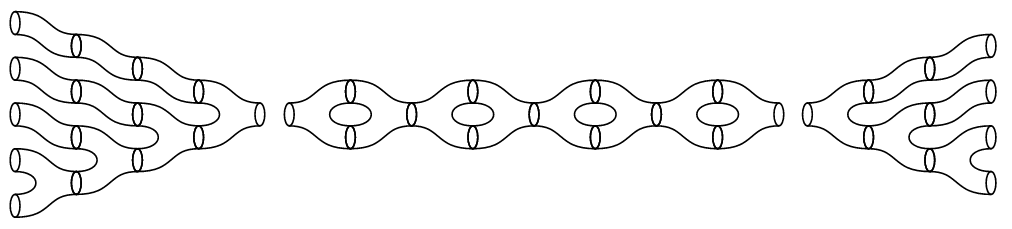

Corollary

(Spider theorem)

If the Frobenius algebra in Cor. is special in that (3) then every linear map of the form

which is

-

entirely the composite of the algebra’s structure maps, ie. of the (co)unit and the (co)product,

-

connected in that it does not decompose as a tensor product of such morphisms,

is equal to the composite, in this order, of

-

copies of

-

copies of .

The “spider theorem” (Cor. ) is called this way in Coecke & Duncan 2008, Thm. 1 (it appears unnamed also in Coecke & Paquette 2008, p. 6) and shares its name with the corresponding “spider diagrams” used in the ZX-calculus for quantum computation (where the Frobenius algebras that appear are those that realize the quantum reader monad as a Frobenius writer monad/cowriter comonad).

Frobenius algebras in polycategories

In fact, Frobenius algebras can be defined in any polycategory, and hence in any linearly distributive category. The essential point is that the monoidal structure used for the monoid structure could be different from the monoidal structure used for the comonoid structure, i.e. we could have but . The compatibility between and in a linearly distributive category (or between their “multicategorical” analogues in a polycategory) is precisely what is required to write down the composites involved in the Frobenius laws. For instance, we can have

and one of the Frobenius laws says that this composite is equal to

This is analogous to how a bimonoid can be defined in any duoidal category. In fact, it is a sort of microcosm principle; it is shown in (Egger2010) that Frobenius monoids in the linearly distributive category Sup are precisely *-autonomous cocomplete posets (and hence, in particular, linearly distributive).

In polycategorical language we can give another unbiased definition of a commutative Frobenius monoid: it is equipped with exactly one morphism of each possible (two-sided) arity, such that any (symmetric) polycategorical composite of two such morphisms is equal to another such. The monoid structure consists of the morphisms of arity and , while the comonoid structure is the morphisms of arity and , and the Frobenius relations say that three ways to compose these to produce a morphism of arity are equal. (The morphism of arity is the composite ; no axiom is required on it, because in a polycategory there is no other morphism to compare it to.) In other words, the free symmetric polycategory containing a commutative Frobenius monoid is the terminal symmetric polycategory. In this way Frobenius algebras are to polycategories in the same way that monoids are to multicategories.

Related concepts

| (co)monad name | underlying endofunctor | (co)monad structure induced by |

|---|---|---|

| reader monad | on cartesian types | unique comonoid structure on |

| coreader comonad | on cartesian types | unique comonoid structure on |

| writer monad | on monoidal types | chosen monoid structure on |

| cowriter comonad | on monoidal types | chosen monoid structure on chosen comonoid structure on |

| Frobenius (co)writer | on monoidal types | chosen Frobenius monoid structure |

References

Frobenius algebras were introduced by Brauer and Nesbitt and were named after Ferdinand Frobenius.

See for instance

-

Samuel Eilenberg, Tadasi Nakayama, On the dimension of modules and algebras. II. Frobenius algebras and quasi-Frobenius rings, Nagoya Math. J. 9 (1955) 1-16 [doi:10.1017/S0027763000023229]

-

Marcelo Aguiar (2000), A note on strongly separable algebras, Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias (Córdoba, Argentina), special issue in honor of Orlando Villamayor, 65, 51–60. (pdf)

- Andrew Baker, Frobenius algebras 2010 (pdf)

On the role of Frobenius algebras in 2d TQFT:

-

Lowell Abrams, Two-dimensional topological quantum field theories and Frobenius algebra, Jour. Knot. Theory and its Ramifications 5, 569-587 (1996) [doi:10.1142/S0218216596000333, ps]

-

John Baez, This Week’s Finds in Mathematical Physics, week268 and week299.

-

Joachim Kock, Frobenius Algebras and 2d Topological Quantum Field Theories, Cambridge U. Press (2004) [doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615443, webpage, course notes pdf, pdf]

-

Joachim Kock, Remarks on the history of the Frobenius equation (2006) [web]

-

Aaron Lauda: Frobenius algebras and ambidextrous adjunctions, Theory and Applications of Categories 16 4 (2006) 84-122 [tac:16-04, arXiv:math/0502550]

(relating to ambidextrous adjunctions and Frobenius monads)

-

Aaron Lauda, Hendryk Pfeiffer, Open-closed strings: two-dimensional extended TQFTs and Frobenius algebras, Topology Appl. 155 (2005) 623-666 [arXiv:0510664, doi:10.1016/j.topol.2007.11.005]

For applications in proof theory of classical and linear logic or linguistics:

-

Martin Hyland, Abstract Interpretation of Proofs: Classical Propositional Calculus, pp. 6-21 in Marcinkowski, Tarlecki (eds.), Computer Science Logic (CSL 2004), LNCS 3210 Springer Heidelberg 2004. (preprint)

-

Richard Garner, Three investigations into linear logic , PhD report Cambridge 2006. (pdf)

-

D. Kartsaklis, M. Sadrzadeh, S. Pulman, Bob Coecke, Reasoning about meaning in natural language with compact closed categories and Frobenius algebras (2014). (arXiv:1401.5980)

Frobenius algebras in linearly distributive categories:

- Jeff Egger: The Frobenius relations meet linear distributivity, Theory and Applications of Categories 242 (2010) [tac:24-2]

See also

-

Aurelio Carboni: Matrices, relations, and group representations, Journal of Algebra 136 2 (1991) 497–529 [doi:10.1016/0021-8693(91)90057-F]

-

Bertfried Fauser, Some Graphical Aspects of Frobenius Structures, preprint (2012). arXiv:1202.6380

-

Stephen Lack (2004), Composing PROPs, Theory and Applications of Categories 13, 147–163. (web)

-

F. W. Lawvere, Ordinal Sums and Equational Doctrines, pp. 141-155 in Eckmann (ed.), Seminar on Triples and Categorical Homology Theory, LNM 80 Springer Heidelberg 1969. (TAC Reprint of vol. 80)

-

Craig Pastro and Ross Street, Weak Hopf monoids in braided monoidal categories, 2008, arXiv:0801.4067

-

R. Rosebrugh, N. Sabadini and R.F.C. Walters (2005), Generic commutative separable algebras and cospans of graphs, Theory and Applications of Categories 15 (Proceedings of CT2004), 164–177. (web)

-

Ross Street (2004), Frobenius monads and pseudomonoids, J. Math. Phys. 45. (doi:10.1063/1.1788852)

-

R. F. C. Walters, R. J. Wood, Frobenius objects in Cartesian cicategories, TAC 20 no. 3 (2008) 25–47. (pdf)

Last revised on August 31, 2025 at 09:17:05. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.