nLab interpretation of quantum mechanics

Context

Physics

physics, mathematical physics, philosophy of physics

Surveys, textbooks and lecture notes

theory (physics), model (physics)

experiment, measurement, computable physics

-

-

-

Axiomatizations

-

Tools

-

Structural phenomena

-

Types of quantum field thories

-

Philosophy

Schools

Of mathematics

Of physics

when it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry. [Bohr, 1920]

Contents

Idea

In the words of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Quantum mechanics is, at least at first glance and at least in part, a mathematical machine for predicting the behaviors of microscopic particles — or, at least, of the measuring instruments we use to explore those behaviors — and in that capacity, it is spectacularly successful: in terms of power and precision, head and shoulders above any theory we have ever had. Mathematically, the theory is well understood; we know what its parts are, how they are put together, and why, in the mechanical sense (i.e., in a sense that can be answered by describing the internal grinding of gear against gear), the whole thing performs the way it does, how the information that gets fed in at one end is converted into what comes out the other. The question of what kind of a world it describes, however, is controversial; there is very little agreement, among physicists and among philosophers, about what the world is like according to quantum mechanics. Minimally interpreted, the theory describes a set of facts about the way the microscopic world impinges on the macroscopic one, how it affects our measuring instruments, described in everyday language or the language of classical mechanics. Disagreement centers on the question of what a microscopic world, which affects our apparatuses in the prescribed manner, is, or even could be, like intrinsically; or how those apparatuses could themselves be built out of microscopic parts of the sort the theory describes.

That is what an interpretation of the theory would provide: a proper account of what the world is like according to quantum mechanics, intrinsically and from the bottom up.

The need for and proper nature of such an interpretation may be subtle and is the subject of much debate. Generally it is maybe worthwhile to keep in mind that all physical theory, well-confirmed as it may be, may usefully be subjected to deeper inspection. This point is well made by Richard Feynman in The character of physical law (1967):

For those people who insist that the only thing that is important is that the theory agrees with experiment, I would like to imagine a discussion between a Mayan astronomer and his student. The Mayans were able to calculate with great precision predictions, for example, for eclipses and for the position of the moon in the sky, the position of Venus, etc. It was all done by arithmetic. They counted a certain number, and subtracted some numbers, and so on. There was no discussion of what the moon was. There was no discussion even of the idea that it went around. They just calculated the time when there would be an eclipse, or when the moon would rise at the full, and so on. Suppose that a young man went to the astronomer and said ‘I have an idea. Maybe those things are going around, and there are balls of something like rocks out there, and we could calculate how they move in a completely different way from just calculating what time they appear in the sky’, ‘Yes’, says the astronomer, ‘and how accurately can you predict eclipses?’ He says, ‘I haven’t developed the thing very far yet’, Then says the astronomer, ‘Well, we can calculate eclipses more accurately than you can with your model, so you must not pay any attention to your idea because obviously the mathematical scheme is better’. There is a very strong tendency, when someone comes up with an idea and says, ‘Let’s suppose that the world is this way’, for people to say to him, ‘What would you get for the answer to such and such a problem?’ And he says ‘I haven’t developed it far enough’. And they say, ‘Well, we have already developed it much further, and we can get the answers very accurately’. So it is a problem whether or not to worry about philosophies behind ideas.

Examples

-

SEP: qm:collapse theories,

Bohr’s standpoint

In (Bohr 49) it is argued that

however far the phenomena transcend the scope of classical physical explanation, the account of all evidence must be expressed in classical terms . The argument is simply that by the word ‘experiment’ we refer to a situation where we can tell others what we have done and what we have learned and that, therefore, the account of the experimental arrangement and the results of the observations must be expressed in unambiguous language with suitable application of the terminology of classical physics.

A proposal for a formalization of this point of view is the concept of the Bohr topos associated with the kinematics of a quantum mechanical system. For more arguments for this see also at order-theoretic structure in quantum mechanics.

As (Peres 97) highlights:

Bohr was very careful and never claimed that there were in nature two different types of physical systems. All he said was that we had to use two different (classical or quantum) languages in order to describe different parts of the world.

and continues:

The peculiar property of the quantum measuring process is that we have to use both descriptions for the same object: namely, the measuring apparatus obeys quantum dynamics while it interacts with the quantum system under study, and at a later stage the same apparatus is considered as a classical object, when it becomes the permanent depositary of information. This dichotomy is the root of the quantum measurement dilemma: there can be no unambiguous classical-quantum dictionary.

Theorems

Related entries

-

quantum measurement, decoherence, consistent histories approach to quantum mechanics

References

Historical arguments

Discussion by the founders of quantum mechanics includes the following.

In

- Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, Nathan Rosen, Can the Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete? Physical Review 47 10 (1935) 777-780 [doi:10.1103/PhysRev.47.777]

it was argued (see at EPR paradox) that quantum mechanics cannot be a complete description of fundamental physics. The contrary was argued in:

- Nils Bohr, Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete? Physical Review 48, 696–702 (1935) (publisher)

The famous assertion (pp. 209) by Bohr that all experiments in quantum mechanics must be possible to describe in “classical terms” (cf. Bohr topos):

- Nils Bohr, Discussion with Einstein on Epistemological Problems in Atomic Physics, in: P. A. Schilpp (ed.), Albert Einstein, Philosopher-Scientist, The Library of Living Philosophers VII Evanston (1949) 201-241, and Niels Bohr Collected Works 7 (1996) 339-381 [doi:10.1016/S1876-0503(08)70379-7]

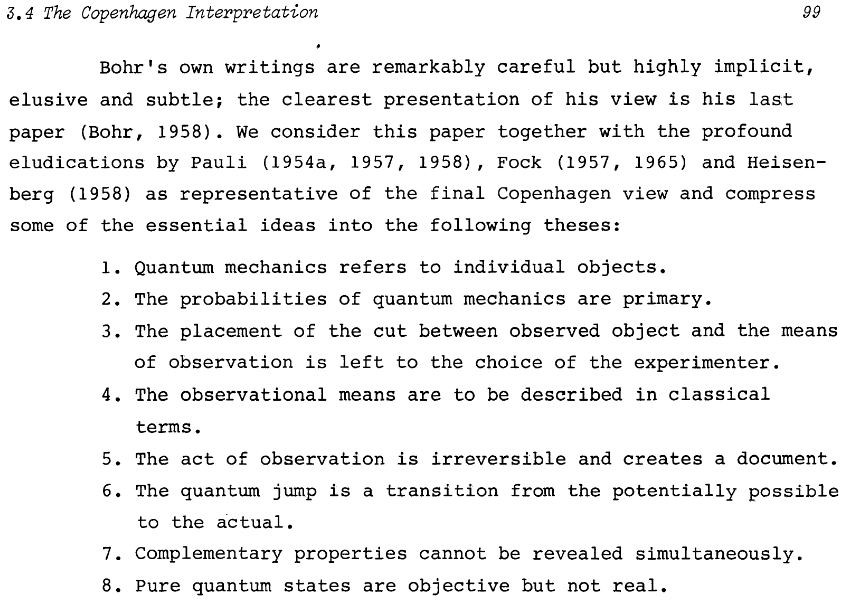

The first systematic statement of what should count as the Copenhagen interpretation (broadly attributed to Werner Heisenberg and Nils Bohr) may be due to Primas (1983) p. 99 (reproduced in Omnès (1994) p. 85):

The many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics:

-

Hugh Everett III, The Theory of the Universal Wavefunction PhD thesis, Princeton (1957) [pdf] reprinted in: De Witt & Graham 1973

(for discussion of the key argument here see at deferred measurement principle the section Deferred measurement and Interpretations)

-

Hugh Everett III, “Relative State” Formulation of Quantum Mechanics, Rev. Mod. Phys. 29 (1957) 454-462 [doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.29.454] (reprinted in De Witt & Graham 1973)

“This total lack of effect of one branch on another also implies that no observer will ever be aware of any ‘splitting’ process. Arguments that the world picture presented by this theory is contradicted by experience, because we are unaware of any branching process, are like the criticism of the Copernican theory that the mobility of the earth as a real physical fact is incompatible with the common sense interpretation of nature because we feel no such motion. In both cases the argument fails when it is shown that the theory itself predicts that our experience will be what it in fact is.”

-

Bryce S. DeWitt, Neill Graham (eds.), The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton Series in Physics, Princeton University Press (1973, 2016) [ISBN:9780691645926, jstor:j.ctt13x0wwk]

The catch-phrase “shut up and calculate” for the agnostic interpretation is due to

- N. David Mermin, What’s Wrong with this Pillow?, Physics Today 42 4 (1989) 9–11 [doi:10.1063/1.2810963]

even though often mis-attributed to Richard Feynman:

- N. David Mermin, Could Feynman Have Said This?, Physics Today 57 5 (2004) 10–11 [doi:10.1063/1.1768652]

Review and textbooks

-

Jagdish Mehra, The quantum principle: Its interpretation and epistemology, Dialectica 27 2 (1973) 75-157 [jstor:42968519]

-

Hans Primas, Pioneer Quantum Mechanics and its Interpretation, Ch. 3 in: Chemistry, Quantum Mechanics and Reductionism, Springer (1983) [doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69365-6]

-

Erhard Scheibe, The logical analysis of quantum mechanics, Pergamon Press (1973)

-

Eugene P. Wigner, Epistemology of Quantum Mechanics, Part I in: Jagdish Mehra (ed.), Philosophical Reflections and Syntheses Vol B.VI in: The Collected Works of Eugene Wigner, Springer (1973) [doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78374-6_5]

-

Roland Omnès, The Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton University Press (1994) [ISBN:9780691036694]

-

Max Tegmark, The Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics: Many Worlds or Many Words?, Fortsch. Phys. 46 (1998) 855-862 [arXiv:quant-ph/9709032]

-

Asher Peres, Interpreting the Quantum World, Stud. History Philos. Modern Physics 29 (1998) 611 [arXiv:quant-ph/9711003]

-

Jeffrey Bub, Interpreting the quantum world, Cambridge University Press (1999) [ISBN:9780521653862]

(focus on the Bub-Clifton theorem)

-

Daniel Greenberger, Wolfgang L. Reiter, Anton Zeilinger, Epistemological and Experimental Perspectives on Quantum Physics, Vienna Circle Institute Yearbook (VCIY) 7 (1999) [doi:10.1007/978-94-017-1454-9]

-

Florian J. Boge, Quantum Mechanics Between Ontology and Epistemology, European Studies in Philosophy of Science (ESPS) 10, Springer (2008) [doi:10.1007/978-3-319-95765-4]

-

David Wallace, Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics, Part 2 in: Dean Rickles (ed.), The Ashgate Companion to Contemporary Philosophy of Physics (2008) 16-98 [ISBN:9780754655183, arXiv:0712.0149]

-

Maximilian Schlosshauer, Decoherence, the measurement problem, and interpretations of quantum mechanics, Rev. Mod. Phys. 76 (2004) 1267-1305 [arXiv;quant-ph/0312059, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.76.1267]

(in view of dynamical quantum decoherence)

-

Edward MacKinnon, Interpreting Physics – Language and the Classical/Quantum Divide, Springer (2012) [doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2369-6]

-

Robert Spekkens, Lectures on Foundations of quantum mechanics (2012) [web]

also: The Quantum Puzzle [web]

An approach to wave function collapse via macroscopic decoherence:

- Wojciech Zurek, Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical, Rev. Mod. Phys. 75 (2003) 715-775 [quant-ph/0105127, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.75.715]

See also:

- Arnold Neumaier, Coherent Quantum Physics: A Reinterpretation of the Tradition, 1st edition, De Gruyter (2019) [ISBN:9783110667295, doi:10.1515/9783110667387]

One quote above is taken from the first paragraphs of

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Quantum mechanics

See also

- Jürg Fröhlich, A Brief Review of the “ETH-Approach to Quantum Mechanics”, Frontiers in Analysis and Probability. Springer (2020) Cham. [arXiv:1905.06603, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-56409-4_2]

Possible-worlds vs. Many-worlds

References which consider, in one way or another, the notions of

in relation to each other:

-

Mario Bunge, Possibility and Probability, in: Foundations of Probability Theory, Statistical Interference, and Statistical Theories of Science, Reidel (1976) 17-34 doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1438-0_2

-

Brian Skyrms, Part III of: Possible Worlds, Physics and Metaphysics, Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition 30 5 (1976) 323-332 jstor:4319099

-

Paul Tappenden, p. 101 (4 of 17) in: Identity and Probability in Everett’s Multiverse, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 51 1 (2000) 99-114 jstor:3541750

-

Daniel Nolan, p. 22 of: Topics in the Philosophy of Possible Worlds, Routledge (2002) ISBN:9780415516303

-

Rod Girle, Ch. 8 of: Possible Worlds, McGill-Queen’s University Press (2003) jstor:j.cttq48cx

-

Simon Saunders, p. 196 in: Chance in the Everett Interpretation, in: Many Worlds?, Oxford University Press (2010) 181–205 doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199560561.003.0008

-

Nuriya Nurgalieva, Lídia del Rio, Inadequacy of Modal Logic in Quantum Settings, EPTCS 287 (2019) 267-297 arXiv:1804.01106, doi:10.4204/EPTCS.287.16

-

Alastair Wilson, p. 20 of: Modal Metaphysics and the Everett Interpretation (2006) philsci:2635, pdf

-

Vladislav Terekhovich, Modal Approaches in Metaphysics and Quantum Mechanics arXiv:1909.10046

-

Alastair Wilson, The Nature of Contingency: Quantum Physics as Modal Realism, Oxford University Press (2020) ISBN:9780198846215

-

Raoni W. Arroyo, Jonnas R. B. Arenhart, Whence deep realism for Everettian quantum mechanics?, Foundations of Physics 52 121 (2022) [arXiv:2210.16713, doi:10.1007/s10701-022-00643-0]

-

Hisham Sati, Urs Schreiber: The Quantum Monadology [arXiv:2310.15735]

Beware that there is also

- Bas C. van Fraassen, Modal interpretation of repeated measurement, Philosophy of Science 64 4 (1997) 669-676 doi:10.1086/392577, SEP review

which, even if some vocabulary is superficially alike, does not refer either to modal logic nor to the many-worlds interpretation.

Last revised on May 28, 2025 at 04:39:12. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.