nLab deferred measurement principle

Context

Quantum systems

-

quantum algorithms:

Contents

Idea

In quantum physics and specifically in quantum information theory, the principle of deferred measurement is a theorem which says that

- any quantum circuit involving quantum measurement of some of the qbits followed by quantum gates controlled by the respective measurement outcomes

is equivalent (equal as a function from given input to output data types) to

- a quantum circuit in which all quantum measurement happens “at the end”, i.e. where no quantum gates are classically controlled by previous measurement results, but all quantumly controlled by coherent control qbits.

The principle can be useful in practice for optimizing quantum circuits. It also clearly relates to the issue of interpretations of quantum mechanics: Since it is the collapse of the wavefunction upon quantum measurement which makes the interpretation of quantum mechanics subtle, it is interesting to note that this collapse may be (arbitrarily) deferred, in a precise sense.

Formalizations

One way to formalize the deferred measurement principle is briefly mentioned in Staton (2015), Axiom B (p. 6 of 12), there proposed as an axiom to be satisfied by quantum programming languages.

Another formalization and proof was proposed by Gurevich & Blass 2021.

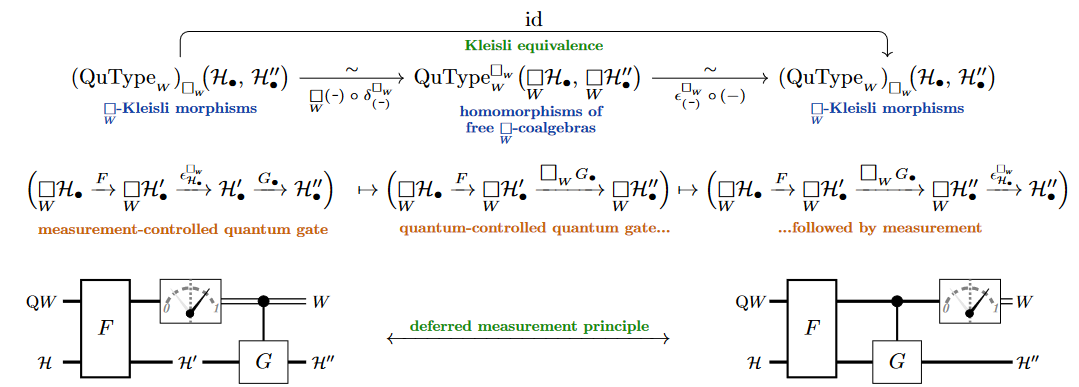

A quick proof of essentially the formulation of Staton (2015) exists in the quantum modal logic of SS23 (cf. quantum circuits via dependent linear types): Here the deferred measurement principle is essentially the Kleisli equivalence for the necessity comonad on dependent linear types, like this (SS23, Prop. 2.38):

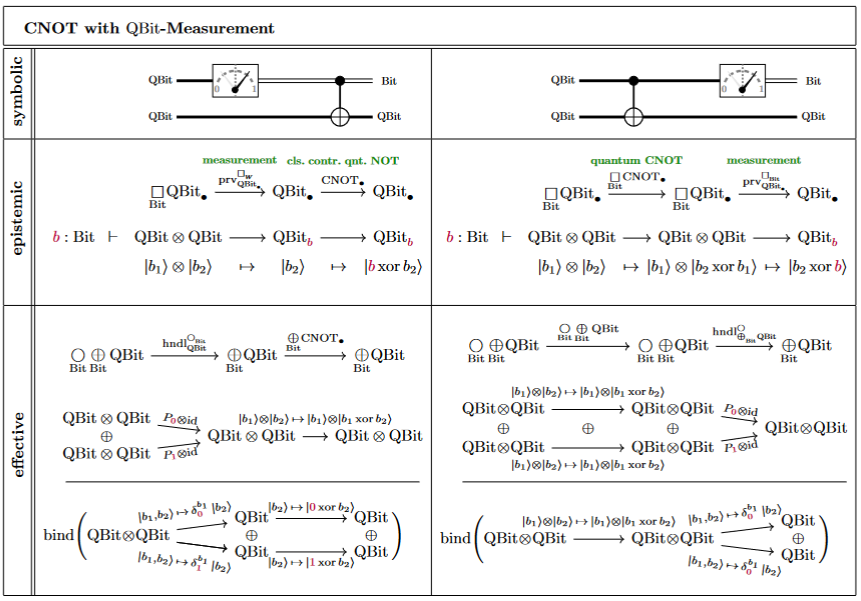

For the example of a CNOT gate:

Interpretation of Deferred measurement

The folklore of quantum physics knows paradoxical-sounding stories under the title of

-

Schrödinger’s cat (1935)

-

Everett’s observers (1957)

-

Wigner’s friend (1961)

The author of these paragraphs asserts that:

-

These are all the same story, recast with different actors: Schrödinger’s cat plays the same role as Everett’s observer A and the same role as Wigner’s friend. The point in any case is that this first observer makes a quantum measurement and (only) ofterwards is himself observed by a second observer.

-

This is just what is formalized by the set-up of the deferred measurement principle:

-

The first observer (called “cat” or “A” or “friend”) is the controlled quantum gate denoted “” above,

-

the quantum system observed by the first observer is above,

-

the state space of the first observer is (before) and (after the observation).

-

The second observer inspecting the scene at the end is the right hand side of the above setup, where the measurement is made at the end of the circuit execution. Before it is made, the first observer may have been in a superposition (in ).

-

But the deferred measurement principle says the outcome is indistinguishable from the situation where the first observer already collapses the original state in .

-

For the record, we recall Everett’s version of this story:

A key argument in the discussion of Everett (1957), which famously led its author to the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, is that intermediate state collapse caused by one observer seems paradoxical, since to a later observer the analogous state collapse occurs (only) at a later time. (This is really the same paradox as that of Schrödinger’s cat, if we grant the cat the role of the first observer).

Everett (1957) casts this into the following prose:

[pp 4:] Isolated somewhere out in space is a room containing an observer, , who is about to perform a measurement upon a system . After performing his measurement he will record the result in his notebook. We assume that he knows the state function of (perhaps as a result of previous measurement), and that it is not an eigenstate of the measurement he is about to perform. , being an orthodox quantum theorist, then believes that the outcome of his measurement is undetermined and that the process is correctly described by Process 1 [state collapse].

In the meantime, however, there is another observer, , outside the room, who is in possession of the state function of the entire room, including , the measuring apparatus, and , just prior to the measurement. is only interested in what will be found in the notebook one week hence, so he computes the state function of the room for one week in the future according to Process 2 [unitary time evolution]. One week passes, and we find still in possession of the state function of the room, which this equally orthodox quantum theorist believes to be a complete description of the room and its contents. If ‘s state function calculation tells beforehand exactly what is going to be in the notebook, then is incorrect in his belief about the indeterminacy of the outcome of his measurement. We therefore assume that ’s state function contains non-zero amplitudes over several of the notebook entries.

At this point, opens the door to the room and looks at the notebook (performs his observation). Having observed the notebook entry, he turns to and informs him in a patronizing manner that since his (‘s) wave function just prior to his entry into the room, which he knows to have been a complete description of the room and its contents, had non-zero amplitude over other than the present result of the measurement, the result must have been decided only when entered the room, so that , his notebook entry, and his memory about what occurred one week ago had no independent objective existence until the intervention by . In short, implies that owes his present objective existence to ’s generous nature which compelled him to intervene on his behalf. However, to ’s consternation, does not react with anything like the respect and gratitude he should exhibit towards , and at the end of a somewhat heated reply, in which conveys in a colorful manner his opinion of and his beliefs, he rudely punctures ’s ego by observing that if ’s view is correct, then he has no reason to feel complacent, since the whole present situation may have no objective existence, but may depend upon the future actions of yet another observer.

It is now clear that the interpretation of quantum mechanics with which we began [the Copenhagen interpretation] is untenable if we are to consider a universe containing more than one observer.

Related concepts

References

While the principle of deferred measurement is a classical statement in quantum information theory, it was not defined or proven in generality and with precision (hence has remained folklore) until Gurevich & Blass 2021 (see the critical discussion of the literature provided there).

Accounts of the informal statement:

- Michael A. Nielsen, Isaac L. Chuang, §4.4 of Quantum computation and quantum information, Cambridge University Press (2000) [doi:10.1017/CBO9780511976667, pdf, pdf]

As an axiom for quantum programming languages:

- Sam Staton, Axiom B (p. 6) in: Algebraic Effects, Linearity, and Quantum Programming Languages, POPL ‘15: Proceedings of the 42nd Annual ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages (2015) 395–40 [doi:10.1145/2676726.2676999, pdf]

See also:

- Wikipedia, Deferred Measurement Principle

General precise statement and proof:

-

Yuri Gurevich, Andreas Blass, Quantum circuits with classical channels and the principle of deferred measurements, Theoretical Computer Science 920 (2022) 21–32 [arXiv:2107.08324, doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2022.02.002]

-

Hisham Sati, Urs Schreiber, Prop. 2.38 in: The Quantum Monadology [arXiv:2310.15735]

Last revised on February 18, 2025 at 08:19:57. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.