nLab Kan extension

Context

Category theory

Concepts

Universal constructions

Theorems

Extensions

Applications

2-Category theory

Definitions

Transfors between 2-categories

Morphisms in 2-categories

Structures in 2-categories

Limits in 2-categories

Structures on 2-categories

Enriched category theory

Background

Basic concepts

Universal constructions

Extra stuff, structure, property

Homotopical enrichment

Limits and colimits

1-Categorical

2-Categorical

(∞,1)-Categorical

Model-categorical

Contents

- Idea

- Definitions

- Ordinary or weak Kan extensions

- Preservation of Kan extensions

- Pointwise Kan extensions

- In terms of weighted (co)limits

- In terms of (co)ends

- In terms of conical (co)limits

- Comparing the definitions

- Absolute Kan extensions

- Of -functors

- In a general 2-category

- Existence

- Properties

- Left Kan extension on representables / fully faithfulness

- Left Kan extensions preserving certain limits

- Kan extension along (op)fibration

- Examples

- Remark on terminology: pushforward vs. pullback

- Related concepts

- References

Idea

The Kan extension of a functor with respect to a functor

is, if it exists, a kind of best approximation to the problem of finding a functor such that

hence to extending the domain of through from to .

More generally, this notion makes sense not only in Cat but in any 2-category.

Similarly, a Kan lift is the best approximation to lifting a morphism through a morphism

to a morphism

Kan extensions are ubiquitous. See the discussion at Examples below.

Definitions

There are various slight variants of the definition of Kan extension. In good cases they all exist and all coincide, but in some cases only some of these will actually exist.

We (have to) distinguish the following cases:

-

“ordinary” or “weak” Kan extensions

These define the extension of an entire functor, by an adjointness relation.

Here we (have to) distinguish further between

-

which define extensions of all possible functors of given domain and codomain (if all of them indeed exist);

-

which define extensions of single functors only, which may exist even if not every functor has an extension.

-

-

These define the value of an extended functor on each object (each “point”) by a weighted (co)limit.

Furthermore, a pointwise Kan extension can be “absolute”.

If the pointwise version exists, then it coincides with the “ordinary” or “weak” version, but the former may exist without the pointwise version existing. See below for more.

Some authors (such as Kelly) assert that only pointwise Kan extensions deserve the name “Kan extension,” and use the term as “weak Kan extension” for a functor equipped with a universal natural transformation. It is certainly true that most Kan extensions which arise in practice are pointwise. This distinction is even more important in enriched category theory.

Ordinary or weak Kan extensions

Global Kan extensions

Let

be a functor. For any other category, write

for the induced functor on the functor categories: this sends a functor to the composite functor .

Definition

If has a left adjoint, typically denoted

or

then this left adjoint is called the ( ordinary or weak ) left Kan extension operation along . For we call the left Kan extension of along .

Similarly, if has a right adjoint, this right adjoint is called the right Kan extension operation along . It is typically denoted

or

The analogous definition clearly makes sense as stated in other contexts, such as in enriched category theory.

Proposition

If is the terminal category, then

Proof

The functor in this case sends objects of to the constant functor on . Notice that for any functor,

-

a natural transformation is the same as a cone over ;

-

a natural transformation is the same as a cocone under .

Therefore the natural hom-isomorphisms of the adjoint functors and

and

assert that

Local Kan extension

There is also a local definition of “the Kan extension of a given functor along ” which can exist even if the entire functor defined above does not. This is a generalization of the fact that a particular diagram of shape can have a limit even if not every such diagram does. It is also a special case of the fact discussed at adjoint functor that an adjoint functor can fail to exist completely, but may still be partially defined. If the local Kan extension of every single functor exists for some given and , then these local Kan extensions fit together to define a functor which is the global Kan extension.

Thus, by the general notion of “partial adjoints”; we say

Definition

The local left Kan extension of a functor along is, if it exists, a functor

equipped with a natural isomorphism

hence a (co)representation of the functor .

The local definition of right Kan extensions along is dual.

As for adjoints and limits, by the usual logic of representable functors this can equivalently be rephrased in terms of universal morphisms:

Definition

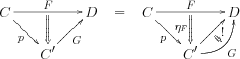

The left Kan extension of along is a functor equipped with a natural transformation .

with the property that every other natural transformation factors uniquely through as

Similarly for the right Kan extension, with the direction of the natural transformations reversed:

By the usual reasoning (see e.g. Categories Work, chapter IV, theorem 2), if these representations exist for every then they can be organised into a left (right) adjoint () to .

Remark

The definition in this form makes sense not just in Cat but in every 2-category. In slightly different terminology, the left Kan extension of a 1-cell along a 1-cell in a 2-category is a pair where is a 2-cell which reflects the object along the functor . Equivalently, it is such a pair such that for every , the function

is a bijection.

In this form, the definition generalizes easily to any n-category for any . If is an -category, we say that the left Kan extension of a 1-morphism along a 1-morphism is a pair , where is a 1-morphism and is a 2-morphism, with the property that for any 1-morphism , the induced functor

is an equivalence of -categories.

Preservation of Kan extensions

We say that a Kan extension is preserved by a functor if the composite is a Kan extension of along , and moreover the universal natural transformation is the composite of with the universal transformation .

Pointwise Kan extensions

If the codomain category admits certain (co)limits, then left and right Kan extensions can be constructed, over each object (“point”) of the domain category out of these: Kan extensions that admit this form are called pointwise. (Reviews include (Riehl, I 1.3)).

The notion of pointwise Kan extensions deserves to be discussed in the general context of enriched category theory, which we do below. The reader may want to skip ahead to the section

which discusses the situation in ordinary (Set-enriched) category theory in terms of ordinary limits (“conical” limits, defined in terms of cones, to be distinguished from the more general weighted limits). While the formulas in that case are classical and fundamentally useful in practice, they do rely heavily on special properties of the enriching category Set.

The general formulation of pointwise Kan extensions in general enriched contexts is

In the case that the codomain category is (co)powered these may be expressed equivalently

First, here is a characterization that doesn’t rely on any computational framework:

Definition

A Kan extension, def. , is called pointwise if and only if it is preserved by all representable functors.

(Categories Work, theorem X.5.3)

In terms of weighted (co)limits

Suppose given and such that for every , the weighted limit

exists. Then these objects fit together into a functor which is a right Kan extension of along . Dually, if the weighted colimit

exists for all , then they fit together into a left Kan extension . These definitions evidently make sense in the generality of -enriched category theory for a closed symmetric monoidal category. (In fact, they can be modified slightly to make sense in the full generality of a 2-category equipped with proarrows.)

In particular, this means that if is small and is complete (resp. cocomplete), then all right (resp. left) Kan extensions of functors exist along any functor .

One can prove that any Kan extension constructed in this way must be pointwise, in the sense of being preserved by all representables as above. Moreover, conversely, if a Kan extension is pointwise, then one can prove that must be in fact a -weighted colimit of , and dually; thus the two notions are equivalent.

Unfolding the definitions of weighted (co)limits, these can be defined as representing objects

Similarly, for -enriched categories, replace Set here with the cosmos for enrichment .

In terms of (co)ends

If the -enriched category is powered over , then the above weighted limit may be re-expressed in terms of an end as

(where again and ).

So in particular when this is

Similarly, if is copowered over , then the left Kan extension is given by a coend.

Example

(coend formula for left Kan extension of presheaves)

The coend formula for the left Kan extension is nicely understood when thinking of and above as opposite categories and for , so that it takes presheaves on along to presheaves on , by the formula

Using the Yoneda lemma to rewrite , this is

In this form one sees that the coend produces the set whose elements are equivalence classes of pairs of morphisms

where two such are regarded as equivalent whenever there is such that

This is particularly suggestive in cases when we may think of the objects of and on the same footing, notably when is a full subcategory inclusion. For in that case we may imagine that a representative pair is a stand-in for the actual pullback of elements of via forming the composite “”, only that this composite is not defined. But the above equivalence relation is precisely that under which this composite would be invariant.

In terms of conical (co)limits

In the case of functors between ordinary locally small categories, hence in the special case of -enriched category theory for Set, there is an expression of a weighted (co)limit and hence a pointwise Kan extension as an ordinary (“conical”, meaning: in terms of cones) (co)limit over a comma category:

Proposition

Let

-

be a small category;

-

have all small limits.

Then the right Kan extension of a functor of locally small categories along a functor exists and its value on an object is given by the limit

where

-

is the comma category;

-

is the canonical forgetful functor.

Likewise, if admits small colimits, the left Kan extension of a functor exists and is pointwise given by the colimit

This appears for instance as (Borceux, I, thm 3.7.2). Discussion in the context of enriched category theory is in (Kelly, section 3.4).

A cartoon picture of the forgetful functor out of the comma category , useful to keep in mind, is

The comma category here is equivalently the category of elements of the functor

Proof

Consider the case of the left Kan extension, the other case works analogously, but dually.

First notice that the above pointwise definition of values of a functor canonically extends to an actual functor:

for any morphism in we get a functor

of comma categories, by postcomposition. This morphism of diagrams induces canonically a corresponding morphism of colimits

Now for the universal property of the functor defined this way. For denote the components of the colimiting cocone by , as in

We now construct in components a natural transformation

for defined as above, and show that it satisfies the required universal property. The components of over are morphisms

Take these to be given by

(this is similar to what happens in the proof of the Yoneda lemma, all of these arguments are variants of the argument for the Yoneda lemma, and vice versa). It is straightforward, if somewhat tedious, to check that these are natural, and that the natural transformation defined this way has the required universal property.

Comparing the definitions

We have seen that if has enough limits or colimits, then a pointwise Kan extension can be defined in terms of these limits, and will necessarily satisfy the universal property described first. However, not all Kan extensions are pointwise: that is, having a universal transformation does not necessarily imply that the individual values of are limits or colimits in its codomain. Non-pointwise Kan extensions can exist even when does not admit very many limits.

It should be noted, though, that pointwise Kan extensions can still exist, and hence the particular requisite limits/colimits exist, even if is not (co)complete. For instance, the Kan extensions that arise in the study of derived functors are pointwise, and in fact absolute (preserved by all functors), even though their codomains are homotopy categories which generally do not admit all limits and colimits.

Non-pointwise Kan extensions seem to be very rare in practice. However, the abstract notion of Kan extension (sometimes called simply “extension”) in a 2-category, and its dual notion of lifting, can be useful in 2-category theory. For instance, bicategories such as Prof admit all right extensions and right liftings; a bicategory with this property may be considered a horizontal categorification of a closed monoidal category.

Absolute Kan extensions

An absolute Kan extension is one which is preserved by all functors out of the codomain of :

(same for right Kan extensions).

The most prominent example of absolute Kan extensions is given by adjoint functors; in fact they can be defined as certain absolute Kan extensions. See there for the precise statement.

Remark

(absolute vs pointwise)

Absolute Kan extensions are always pointwise, as the latter can be defined as those preserved by representables; there are (lots of) examples of pointwise Kan extensions which are not absolute.

Note that in a general 2-category, absolute Kan extensions make perfect sense, while for defining pointwise ones more structure is needed: comma objects and/or some structure which would let us work with (co)limits inside that 2-category (such as a (co)Yoneda structure or a proarrow equipment).

Of -functors

The global definition of Kan extensions for functors in terms of left/right adjoints to pullbacks may be interpreted essentially verbatim in the context of (∞,1)-categories

See at (∞,1)-Kan extension.

In a general 2-category

The Kan extension of a functor may be regarded more abstractly as an extension-problem in the 2-category Cat of categories. The same extension problem can be stated verbatim in any 2-category and hence there is a corresponding more general notion of Kan extensions of 1-morphisms in 2-categories. This is discussed in (Lack 09, section 2.2).

The question of defining a pointwise Kan extension in a general 2-category is more subtle, and there are at least two distinct approaches. If the 2-category has comma objects, then we can define a Kan extension to be pointwise if it remains a Kan extension upon pasting with any comma object; this is an “internalization” of the above definition in terms of conical colimits. On the other hand, in a 2-category equipped with proarrows we can define pointwise Kan extensions as particular weighted (co)limits using a representable weight; this generalizes the above definition as a weighted (co)limit.

In some 2-categories such as , both definitions agree; but in others they do not, and in general in this case it is the equipment-theoretic version that is “correct”. For instance, in the equipment-theoretic version gives the right notion of pointwise Kan extension, whereas the comma-object one is too strong.

As a concrete example, let , so that ; then comma objects are not informative enough because they “don’t see the 2-cells”. In even more specificity, let be the walking 2-cell and the walking pair of parallel 1-morphisms, with and the inclusions of the common domain of the parallel 1-morphisms; then the equipment-theoretic-pointwise is constant at the domain object, whereas the comma-object-pointwise does not exist. See (Koudenburg, Example 2.24) for details.

Existence

The following reproduces a MathOverflow answer by Ivan Di Liberti:

Lemma

(Kan). Let be a span where is small and is (small) cocomplete. Then the left Kan extension exists.

Kan extensions are a useful tool in everyday practice, with applications in many different topics of category theory. In this lemma (which is one of the most used in this topic) the set-theoretic issue is far from being hidden: needs to be small (with respect to ! There is no chance that the lemma is true when is a large category. Indeed since colimits can be computed via Kan extensions, the lemma would imply that every (small) cocomplete category is large cocomplete, which is not allowed because cocomplete small categories are posets. Also, there is no chance to solve the problem by saying: well, let’s just consider to be large-cocomplete, again because cocomplete small categories are posets.

This problem is hard to avoid because the size of the categories of our interest is as a fact always larger than the size of their inhabitants (this just means that most of the time Ob is a proper class, as big as the size of the enrichment).

Notice that the Kan extension problem recovers the adjoint functor theorem one, because adjoints are computed via Kan extensions of identities of large categories. Indeed, in that case, the solution set condition is precisely what is needed in order to cut down the size of some colimits that otherwise would be too large to compute, as can be synthesized by the sharp version of the Kan lemma.

Lemma

Sharp Kan lemma. Let be a span where is a small presheaf for every and is (small) cocomplete. Then the left Kan extension exists.

Indeed this lemma allows to be large, but we must pay a tribute to its presheaf category: needs to be somehow locally small (with respect to Ob).

Lemma

Kan lemma Fortissimo. Let be a functor. The following are equivalent:

- for every where is a small-cocomplete category, exists.

- exists, where is the Yoneda embedding in the category of small presheaves .

- is a is small presheaf for every .

Even unconsciously, the previous discussion is one of the reasons of the popularity of locally presentable categories. Indeed, having a dense generator is a good compromise between generality and tameness. As an evidence of this, in the context of accessible categories the sharp Kan lemma can be simplified.

Lemma

Tame Kan lemma. Let be a span of accessible categories, where is an accessible functor and is (small) cocomplete. Then the left Kan extension exists.

References for Sharp. I am not aware of a reference for this result. It can follow from a careful analysis of Prop. A.7 in my paper Codensity: Isbell duality, pro-objects, compactness and accessibility. The structure of the proof remains the same, presheaves must be replaced by small presheaves.

References for Tame. This is an exercise, it can follow directly from the sharp Kan lemma, but it’s enough to properly combine the usual Kan lemma, Prop A.1&2 of the above-mentioned paper, and the fact that accessible functors have arity.

Properties

Left Kan extension on representables / fully faithfulness

Let be a suitable enriching category (a cosmos). Notably may be Set.

Proposition

For a -enriched functor between small -enriched categories we have

-

the left Kan extension along takes representable presheaves to their image under :

for all .

-

if is a full and faithful functor then and in fact the -unit of an adjunction is a natural isomorphism

whence it follows (by this property of adjoint functors) that is itself a full and faithful functor.

The second statement appears for instance as (Kelly, prop. 4.23).

Proof

For the first statement, using the coend formula for the left Kan extension above we have naturally in the expression

Here the last step is called sometimes the co-Yoneda lemma. It follows for instance by observing that is equivalently dually the expression for the left Kan extension of the non-representable along the identity functor.

Similarly for the second, if is any -enriched functor with copowered over , then its left Kan extension evaluated on the image of is

Left Kan extensions preserving certain limits

The following statement says that left exact functors into toposes have left exact left Kan extension along the Yoneda embedding (Yoneda extension) and that this is the inverse image of a geometric morphism of sheaf toposes if the original functor preserves covers.

(We state this in (∞,1)-category theory, the same statement holds true in plain category theory by just disregarding all occurrences of “”.)

Proposition

Let be an (∞,1)-topos and let be an (∞,1)-site with (∞,1)-sheaf (∞,1)-category . Then the (∞,1)-functor

given by precomposition with ∞-stackification/sheafification and with the (∞,1)-Yoneda embedding is a full and faithful (∞,1)-functor. Moreover, its essential image consisist of those (∞,1)-functors which are left exact and which preserve covers in that for a covering in , then is an effective epimorphism in .

This appears as Lurie, HTT, prop. 6.2.3.20.

Remark

Prop. is a central statement in the theory of classifying toposes. See there for more.

For more discussion of left exactness properties preserved by left Kan extension see also (Borceux-Day, Karazeris-Protsonis).

Kan extension along (op)fibration

Proposition

Let be a small opfibration of categories, and let be a category with all small colimits. Then for each the inclusion

of the fiber over into the comma category given by

has a left adjoint. given by

where is a coCartesian lift of .

Therefore (by the discussion here) it is a cofinal functor. Accordingly, the local formula for the left Kan extension

is equivalently given by taking the colimit over the fiber:

A similar result holds for -categories. See Lurie, HTT, prop. 4.3.3.10, set and .

Examples

The central point about examples of Kan extensions is:

Kan extensions are ubiquitous.

To a fair extent, category theory is all about Kan extensions and the other universal constructions: limits, adjoint functors, representable functors, which are all special cases of Kan extensions – and Kan extensions are special cases of these.

Listing examples of Kan extensions in category theory is much like listing examples of integrals in analysis: one can and does fill books with these. (In fact, that analogy has more to it than meets the casual eye: see coend for more).

Keeping that in mind, we do list some special cases and special classes of examples that are useful to know. But any list is necessarily wildly incomplete.

General

-

For the point, the right Kan extension of is the limit of , and the left Kan extension is the colimit .

-

For a morphism of sites coming from a functor of the underlying categories, the left Kan extension of functors along is the inverse image operation .

-

see also examples of Kan extensions

Non-pointwise Kan extensions

Examples of Kan extensions that are not point-wise are discussed in Borceux, exercise 3.9.7.

Restriction and extension of sheaves

For more on the following see also

The basic example for left Kan extensions using the above pointwise formula, is in the construction of the pullback of sheaves along a morphism of topological spaces. Let be a continuous map and a presheaf over . Then the formula clearly defines a presheaf on , which is in fact a sheaf if is. On the other hand, given a presheaf over we can not define pullback presheaf because might not be open in general (unless is an open map). For Grothendieck sites such would not make even sense. But one can consider approximating from above by for all which are open and take a colimit of this diagram of inclusions (all are bigger, so getting down to the lower bound means going reverse to the direction of inclusions). But inclusion implies . The latter identity involves only open sets. Thus we take a colimit over the comma category of . If is a sheaf, the colimit understood as a rule is still not a sheaf, we need to sheafify. The result is sheaf-theoretic pullback

which is a sheaf, and one can analyze this construction to show that is a left adjoint to . This usage of left Kan extension persists in the more general case of Grothendieck topologies.

Kan extension in physics

We list here some occurrences of Kan extensions in physics.

Notice that since, by the above discussion, Kan extensions are ubiquitous in category theory and are essentially equivalent to other standard universal constructions such as notably co/limits, to the extent that there is a relation between category theory and physics at all, it necessarily also involves Kan extensions, in some guise. But here is a list of some example where they appear rather explicitly.

-

In extended quantum field theory on open and closed manifolds, usually the theory “in the bulk” (on closed manifolds) is induced by “extending” that “on the boundary”, and in good cases this extension is explicitly a (homotopy)-Kan extension. This is the case notably for 2d TQFT in the form of TCFT (Costello 04), see at TCFT – Classification for details.

-

When path integral quantization is formalized in terms of fiber integration in generalized cohomology (as surveyed at motivic quantization) then the push-forward step, hence the path integral itself, is given by left homotopy Kan extension of parameterized spectra. For explicit details see (Nuiten 13, section 4.1), also (Schreiber 14, section 6.2). By example 6.3, a special case of this is the integration formulas via Kan extension in (Hopkins-Lurie 14, section 4).

Remark on terminology: pushforward vs. pullback

Generally, for a functor, the induced “precomposition” functor on functor categories

is spoken of as pulling back a functor on to a functor on , as this operation goes in the direction opposite to that of itself. For this reason, we have above denoted this functor by . Likewise, one might call the (left or right) Kan extensions along a push forward of functors from to functors on .

This notation also coincides with that for geometric morphisms in one case: any functor between small categories induces a geometric morphism of presheaf toposes, whose inverse image is the above and whose direct image is the right Kan extension functor. Note that preserves (finite) limits, as required of an inverse image functor, since it has a left adjoint, namely left Kan extension.

On the other hand, if is additionally a flat functor, then the above precomposition functor is also the direct image of a geometric morphism, whose inverse image is given by left Kan extension (which preserves finite limits when is flat). More generally, if and are sites and is flat and preserves covering families (i.e. it is a morphism of sites), then precomposition is the direct image of a geometric morphism between sheaf toposes.

For example, and might be the posets and of open subsets of topological spaces (or locales) and and inclusions, in which case

come from continuous maps of topological spaces going the other way

via the usual inverse image of open subsets.

Thus, in such cases, the functor , which looks like a pullback of functors along , corresponds geometrically to a push-forward of (pre)sheaves along . Therefore, in presheaf literature (such as Categories and Sheaves) the precomposition functor induced by is usually denoted and not .

It is however noteworthy that also the opposite perspective does occur in geometrically motivated examples. For instance

-

if is the discrete category on smooth space and is the discrete category on the smooth space underlying the Lie group , then smooth functors (i.e. functors internal to smooth spaces) can be identified with smooth -valued functions on , and the functor on these functor categories induced by a smooth functor does correspond to the familiar notion of pullback of functions;

-

and similar in higher degrees: if is the smooth path groupoid of a smooth space and the smooth group regarded as a one-object Lie groupoid, then smooth functors correspond to smooth 1-forms on , and precomposition with a smooth functor corresponds to the familiar notion of pullback of 1-forms.

This means that whether or not Kan extensions correspond geometrically to pushforward or to pullback depends on the way (covariant or contravariant) in which the domain categories , are identified with geometric entities.

Related concepts

-

Kan extension, (∞,1)-Kan extension

References

The original definition is due to Daniel M. Kan, found in the paper that also defined adjoint functors and limits:

- Daniel M. Kan, Adjoint functors, Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 87:2 (1958), 294–294 (doi:10.1090/s0002-9947-1958-0131451-0).

Textbook sources include

-

Francis Borceux, section 3.7 of Handbook of Categorical Algebra I

-

Kashiwara and Shapira, section 2.3 in Categories and Sheaves

The book

has a famous treatment of Kan extensions with a statement: “The notion of Kan extensions subsumes all the other fundamental concepts in category theory”. Of course, many other fundamental concepts of category theory can also be regarded as subsuming all the others.

Lecture notes with an eye towards applications in homotopy theory include

- Emily Riehl, Chapter 1 in: Categorical Homotopy Theory, Cambridge University Press (2014) [doi:10.1017/CBO9781107261457, pdf]

For Kan extensions in the context of enriched category theory see

- Eduardo Dubuc, Kan extensions in enriched category theory, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Vol. 145 Springer-Verlag, Berlin-New York 1970 xvi+173 pp.

and chapter 4 of

- Max Kelly, Basic Concepts of Enriched Category Theory,

Cambridge University Press, Lecture Notes in Mathematics 64, 1982, Republished in: Reprints in Theory and Applications of Categories, No. 10 (2005) pp. 1-136 (tac:tr10, pdf)

The (∞,1)-category theory notion is discussed in section 4.3 of

For uses of Kan extension in the study of algebras over an algebraic theory see

- Paul-André Melliès and Nicholas Tabareau, Free models of T-algebraic theories computed as Kan extensions (web)

Preservation of certain limits by left Kan extended functors is discussed in

-

Francis Borceux, and Brian Day, On product-preserving Kan extension, Bulletin of the Australian Mathematical Society, Vol 17 (1977), 247-255 (pdf)

-

Panagis Karazeris, Grigoris Protsonis, Left Kan extensions preserving finite products, (pdf)

The general notion of extensions of 1-morphisms in 2-categories is discussed in

- John W. Gray, Quasi-Kan extensions for 2-categories, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 80:1 (1974) 142-147 pdf

- Steve Lack, A 2-categories companion, in John Baez, Peter May, Towards Higher Categories, Springer, (2009) (arXiv:math/0702535)

- Ross Street, Pointwise extensions and sketches in bicategories, arXiv:1409.6427

- Seerp Roald Koudenburg, Algebraic weighted colimits, arXiv

For the notion of (2-dimensional) (pointwise) bi-Kan extensions of pseudofunctors, see

-

Fernando Lucatelli Nunes, On biadjoint triangles, TAC 31-9

-

Fernando Lucatelli Nunes, Pseudo-Kan extensions and descent theory, TAC 33-15

and its applications to the theory of (2-dimensional) flat functors can be seen in

- M.E. Descotte, E.J. Dubuc, M. Szyld, On the notion of flat 2-functors, Adv. Math, arXiv:1610.09429

For a treatment of left Kan extensions as ‘partial colimits’, see

- Paolo Perrone, Walter Tholen, Kan extensions are partial colimits, Applied Categorical Structures, 2022. (arXiv:2101.04531)

Last revised on June 27, 2025 at 11:50:47. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.