nLab BHK interpretation

Context

Type theory

natural deduction metalanguage, practical foundations

type theory (dependent, intensional, observational type theory, homotopy type theory)

computational trinitarianism =

propositions as types +programs as proofs +relation type theory/category theory

Constructivism, Realizability, Computability

constructive mathematics, realizability, computability

propositions as types, proofs as programs, computational trinitarianism

Constructive mathematics

Realizability

Computability

Contents

Idea

In constructive mathematics (originally: intuitionistic logic), the BHK interpretation of logical connectives (due to Kolmogorov (1932, p. 59), Troelstra (1969, §2), see the comments on attribution below) is such that the resulting proposition is regarded as true only if it is possible to construct a proof of its assertion.

For instance, to assert a logical conjunction (“and”) or a universal quantification (“for all”) is taken to mean to provide a proof for all the instances. Dually, but more notably, to assert a logical disjunction (“or”) or an existential quantification (“exists”) is taken to mean to prove one of the instances, so that there is no intuitionistic existence statement without construction of an example (the “disjunction property”, see there).

This constructive interpretation of logical truth is the crux of the rejection of the principle of excluded middle in intuitionism/constructive mathematics, for it implies that to prove (which may superficially/classically seem tautologous) one must prove or one must prove — but neither proof may be known (e.g. if = Riemann hypothesis). (Here the classical mathematician is regarded as “idealistic” in their assumption that either case must hold, even if it is impossible to tell which one.)

In short this means that a proposition is regarded a true if there is an algorithm, hence a computable function, to realize its proof whence one also speaks of the realizability interpretation. Closely related to the point of being synonymous is the paradigm of propositions as types and proofs as programs, also known as the Curry-Howard correspondence in type theory.

Indeed, the fully formal version of the BHK interpretation may be understood as being the inference rules, specifically the term introduction rules, of intuitionistic type theory (as amplified in Girard (1989, §2) and Martin-Löf (1996, Lec 3)).

In mathematical foundations

Dependent type theory

In dependent type theory, propositions are usually defined as subsingletons, types in which given and one can construct an identification . Predicates on a type are families of subsingletons indexed by .

The BHK interpretation of predicate logic is defined using basic type theoretic operations: Given two propositions and , purely or is given by an element of the binary sum type

and the pure existential quantifier of a predicate on a type is given by an element of the dependent sum type

Also,

-

false is given by the empty type

-

true is given by any contractible type

-

implication is given by the function type

-

conjunction is given by the binary product type

-

and the universal quantification is given by the indexed Cartesian product

Set theory

The BHK interpretation of logic is also possible to express in set theory; in particular, in the internal logic of the resulting category of sets that arises from the set theory.

Propositions in the internal logic are given by the subsingletons, which are the sets in which for all and in , . Given any singleton , any external proposition can be turned into an subsingleton via the subset

This means that one can use the set-theoretic operations to define the BHK interpretation of predicate logic: Given two propositions and , purely or is given by an element of the binary disjoint union

and the pure existential quantifier of a predicate on a set is given by an element of the indexed disjoint union

Also,

-

false is given by the empty set, which is isomorphic to

-

true is given by any singleton, which is isomorphic to

-

implication is given by the function set

-

conjunction is given by the binary Cartesian product

-

and the universal quantification is given by the indexed Cartesian product

Using this one can translate any theorems and proofs of set-level mathematics done in dependent type theory using the BHK interpretation over to set theory.

Historical versions

The BHK interpretation evolved from a rather informal statement in Kolmogorov (1932, p. 59), over a more pronounced but still informal statement due to Troelstra (1969, p. 5), to the modern inference rules in intuitionistic type theory due to Martin-Löf 75 (gentle exposition in Martin-Löf (1996, Lec 3)):

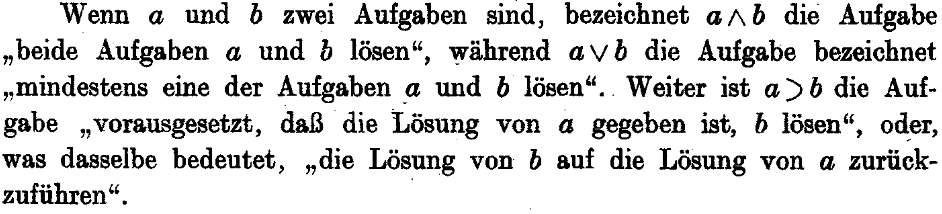

From Kolmogorov (1932, p. 59):

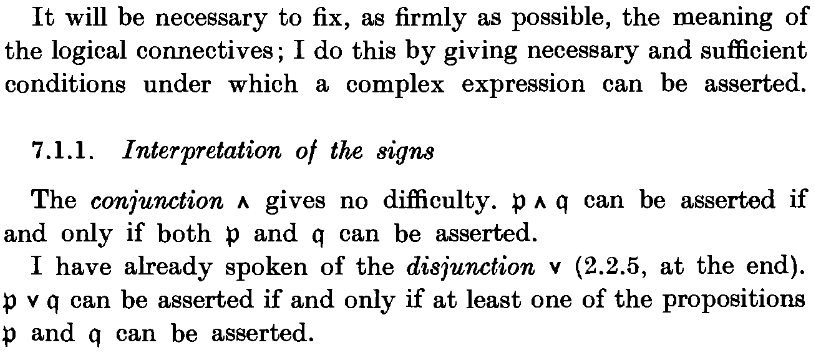

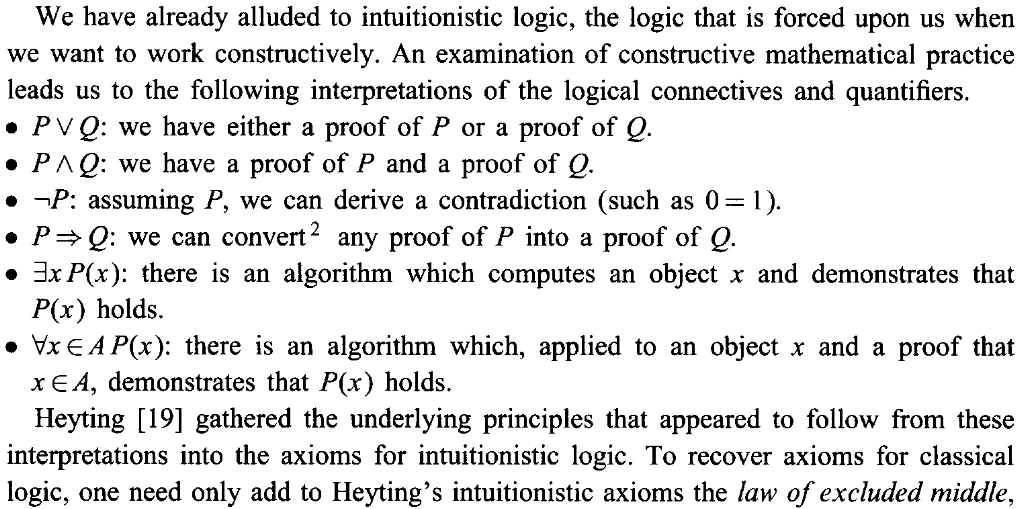

From Heyting (1956, p. 97):

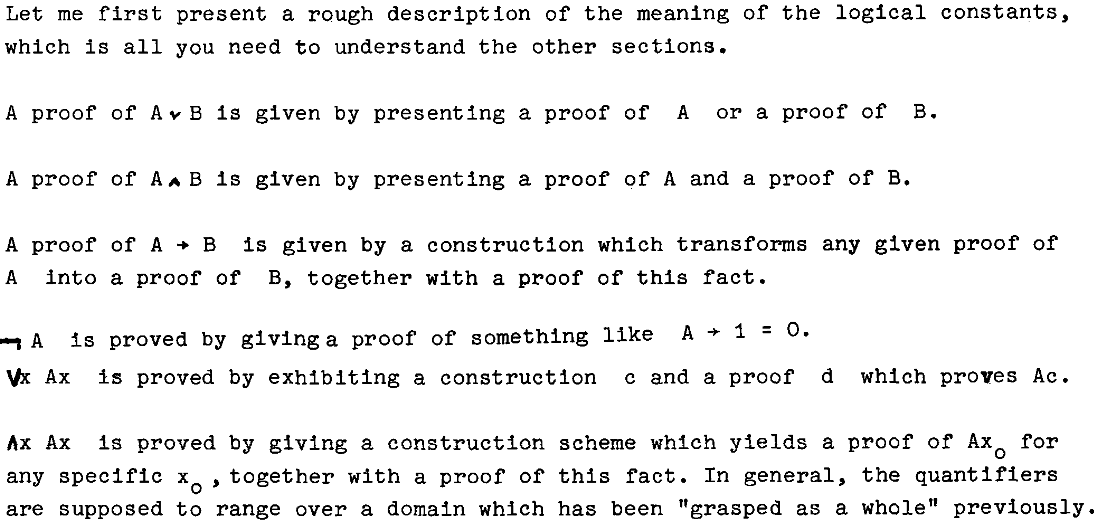

From Troelstra (1969, p. 5):

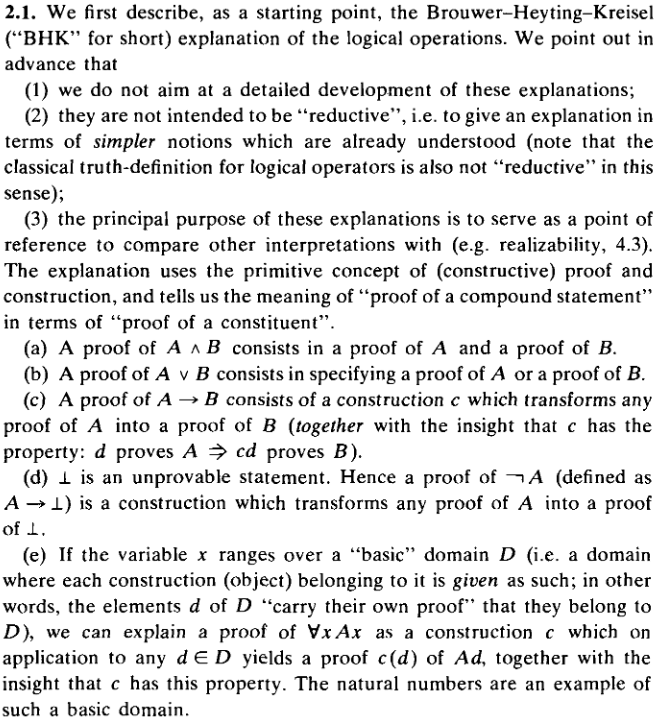

From Troelstra (1977, p. 977):

From Troelstra & van Dalen (1988):

From Bridges (1999), p. 96:

The analogous discussion for inference rules in intuitionistic type theory is then given in Martin-Löf (1975), reviewed in Girard (1989, §2) and with more emphasis in Martin-Löf (1996, Lec 3).

Attribution

The idea of the interpretation is clearly expressed in Kolmogorov (1932, p. 59), though rather briefly and in unusual terminology: Instead of propositions, Kolmogorov speaks of Aufgaben (Deutsch for “tasks”, but here in the sense used in math classes where it means “exercises” or “mathematical problems”) in order to amplify the constructive aspects (he expands it out to Konstruktionsaufgabe, meaning “construction task”).

While Arend Heyting may have been speaking of the idea of the “proof interpretation” of propositions since the 1930s, the first recognizable statement of what later was called the BHK interpretation is given in Heyting (1956, §7.1.1).

The statement of the interpretation close to its modern formulation (but clearly of the same conceptual content as previously expressed in Kolmogorov (1932, p. 59) and Heyting (1956, §7.1.1)) was then made explicit in Troelstra (1969, §2), where it is not attributed to anyone but presented as if the author’s invention.

Later, Troelstra (1977, §2) credits the idea to “Brouwer-Heyting-Kreisel (BHK)”, not mentioning Kolmogorov — indeed Kreisel (1965) is the only reference that Troelstra (1969, §2) makes explicit use of. (While this is the origin of the term “BHK interpretation”, the adjustment/correction of its expanded version by exchanging “Kreisel” for “Kolmogorov” seems to be due to Troelstra (1990, §2.1).)

Still later, Girard (1989, §1.2.2) presents the same idea as “Heyting’s semantics” (not mentioning anyone else, nor actually citing Heyting).

More discussion of this history is in SEP: “The Development of Intuitionistic Logic”.

Notice that Brouwer never explicitly formulated any interpretation of the kind that Troelstra (1977, §2) attributes to him, and in fact remained against all formalism his entire life. (His role in this history is to provide motivation and inspiration for Heyting and Kolmogorov.) Moreover, Escardo & Xu (2015) have shown that Brouwer’s famous intuitionistic theorem “all functions are continuous” is actually inconsistent under a literal version of this interpretation (i.e. without including propositional truncation).

Thus, perhaps it should be called the “Heyting-Kolmogorov” interpretation.

Related concepts

References

Original articles on intuitionism and, eventually, on intuitionistic logic:

-

Arend Heyting, Die intuitionistische Grundlegung der Mathematik, Erkenntnis 2 (1931) 106-115 [jsotr:20011630, pdf]

-

Andrey Kolmogorov, Zur Deutung der intuitionistischen Logik, Math. Z. 35 (1932) 58-65 [doi:10.1007/BF01186549]

-

Hans Freudenthal, Zur intuitionistischen Deutung logischer Formeln, Comp. Math. 4 (1937) 112-116 [numdam:CM_1937__4__112_0]

-

Arend Heyting, Bemerkungen zu dem Aufsatz von Herrn Freudenthal “Zur intuitionistischen Deutung logischer Formeln”, Comp. Math. 4 (1937) 117-118 [doi:CM_1937__4__117_0]

-

L. E. J. Brouwer, Points and Spaces, Canadian Journal of Mathematics 6 (1954) 1-17 [doi:10.4153/CJM-1954-001-9]

Early monographs:

-

Arend Heyting, Intuitionism: An introduction, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics, North-Holland (1956, 1971) [ISBN:978-0720422399]

-

Georg Kreisel, Section 2 of: Mathematical Logic, in T. Saaty et al. (ed.), Lectures on Modern Mathematics III, Wiley New York (1965) 95-195

-

Anne Sjerp Troelstra, Dirk van Dalen, Section 3.1 of: Constructivism in Mathematics – An introduction, Vol 1, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics 121, North Holland (1988) [ISBN:9780444702661]

Early historical review:

- Anne Sjerp Troelstra, On the Early History of Intuitionistic Logic, in Mathematical Logic, Springer, (1990) [doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0609-2_1]

Recognizable formulation of the so-called “BHK interretation” first appears in:

(who however speaks not of propositions but of Aufgaben, i.e. “tasks”, here in the sense of: “mathematical problems”)

(who is maybe the first to speak of the “meaning of logical connectives”) and then

- Anne Sjerp Troelstra, §2 of: Principles of Intuitionism, Lecture Notes in Mathematics 95 Springer Heidelberg (1969) [doi:10.1007/BFb0080643]

(where it is presented as if the author’s invention) and then recalled in

- Anne Sjerp Troelstra, §2 of: Aspects of Constructive Mathematics, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics 90 973-1052 (1977) [doi:10.1016/S0049-237X(08)71127-3]

(where the same is now called the “Brouwer-Heyting-Kreisel (BHK) explanation” — not mentioning Kolmogorov).

and later recalled in the context of constructive analysis:

- Douglas Bridges, p. 96 of: Constructive mathematics: a foundation for computable analysis, Theoretical Computer Science 219 1–2 (1999) 95-109 [doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(98)00285-0]

This lead to the formulation of intuitionistic type theory in

- Per Martin-Löf, An intuitionistic theory of types: predicative part, in: H. E. Rose, J. C. Shepherdson (eds.), Logic Colloquium ‘73, Proceedings of the Logic Colloquium, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics 80, Elsevier (1975) 73-118 [doi:10.1016/S0049-237X(08)71945-1, CiteSeer]

reviewed in

- Jean-Yves Girard (translated and with appendices by Paul Taylor and Yves Lafont), §1.2.2 of: Proofs and Types, Cambridge University Press (1989) [ISBN:978-0-521-37181-0, webpage, pdf]

(where it is called Heyting semantics) and then in

- Per Martin-Löf, Lecture 3 of: On the Meanings of the Logical Constants and the Justifications of the Logical Laws, Nordic Journal of Philosophical Logic, 1 1 (1996) 11-60 [pdf, pdf]

See also:

-

Wikipedia, BHK interpretation

-

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Development of Intuitionistic Logic

-

Wouter Pieter Stekelenburg, Realizability Categories, (arXiv:1301.2134).

-

Martin Escardo, Chuangjie Xu, The inconsistency of a Brouwerian continuity principle with the Curry–Howard interpretation, 13th International Conference on Typed Lambda Calculi and Applications (TLCA 2015), Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs) 38 (2015) [doi:10.4230/LIPIcs.TLCA.2015.153, pdf]

-

E. G. F. Díez, Five observations concerning the intended meaning of the intuitionistic logical constants , J. Phil. Logic 29 no. 4 (2000) pp.409–424 . (preprint)

Links to many papers on realizability and related topics may be found here.

For a comment see also

- Robert Harper, Extensionality, Intensionality, and Brouwer’s Dictum (web)

Last revised on August 2, 2025 at 09:49:00. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.