nLab dependent sum type

Context

Type theory

natural deduction metalanguage, practical foundations

type theory (dependent, intensional, observational type theory, homotopy type theory)

computational trinitarianism =

propositions as types +programs as proofs +relation type theory/category theory

Dependent sum types

Idea

In dependent type theory, what is traditionally called the dependent sum type (really: dependent coproduct) of a dependent type is the type whose terms are ordered pairs with and — whence also called the dependent pair type.

In the categorical semantics of dependent type theory in fibration categories, the dependent sum corresponds to internal coproducts over an index type.

In the special case that is independent of this reduces to the product type , while in the special case that Bool it reduces to a binary coproduct.

This notion is dual (in fact: adjoint) to the corresponding notion of dependent product type:

| type former: | meaning of terms: |

|---|---|

| dependent product | dependent function / section of bundle |

| dependent coproduct (aka: dependent sum) | dependent pair / element of bundle |

Overview

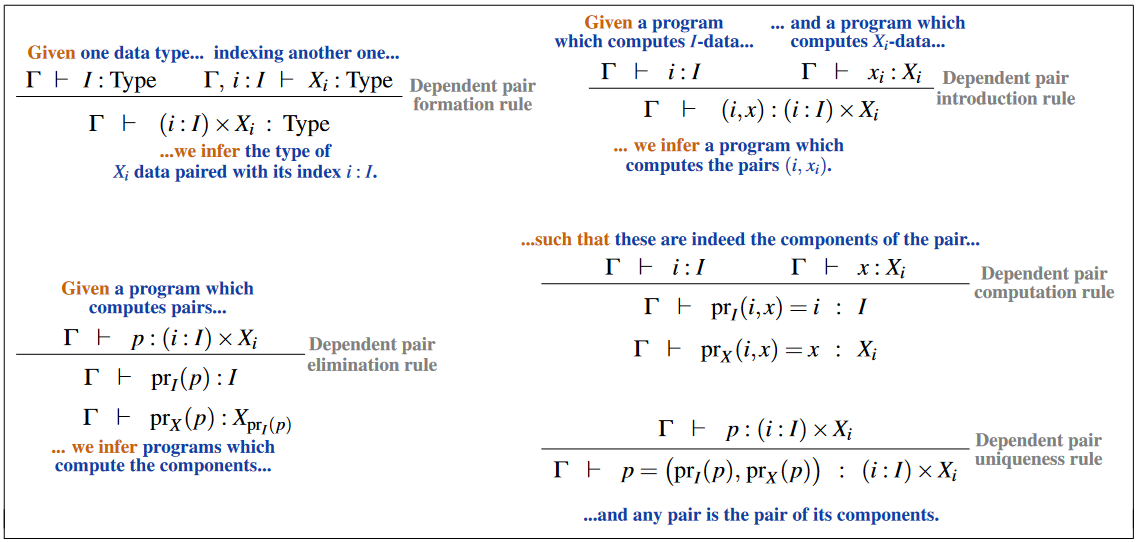

The inference rules for dependent pair types (aka “dependent sum types” or “-types”):

Definition

Like any type constructor in type theory, the dependent sum type is specified by rules saying when we can introduce it as a type, how to construct terms of that type, how to use or “eliminate” terms of that type, and how to compute when we combine the constructors with the eliminators.

In natural deduction

We assume that our dependent sum types have typal conversion rules, as those are the most general of the conversion rules. Both the propositional and judgmental conversion rules imply the typal conversion rules by the structural rules for propositional and judgmental equality respectively.

The formation and introduction rules are the same for both the positive and negative dependent sum types

Formation rules for dependent sum types:

Introduction rules for dependent sum types:

As a positive type

- Elimination rules for dependent sum types:

- Computation rules for dependent sum types:

- Uniqueness rules for dependent sum types:

Given a pointed h-proposition , the positive dependent sum type results in being an equivalence of types.

As a negative type

- Elimination rules for dependent sum types:

- Computation rules for dependent sum types:

- Uniqueness rules for dependent sum types:

Given a pointed h-proposition , the negative dependent sum type results in being a quasi-inverse function of , rather than an equivalence of types. Thus, the positive definition is preferred to the negative definition. Alternatively, the negative dependent sum type should be defined as a coinductive type rather than an inductive type.

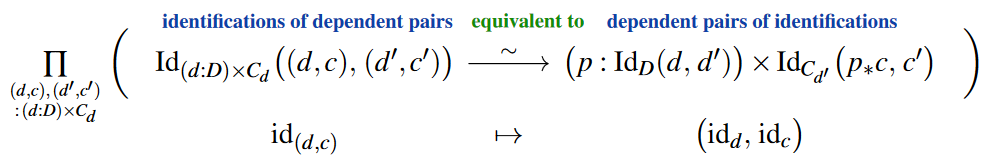

Extensionality principle

The extensionality principle for the dependent sum type states that there is an equivalence of types between the identity type of a dependent sum type and the dependent sum of its component’s identity types:

The comparison function itself is readily obtained by Id-induction. That this indeed constitutes an equivalence of types is shown in UFP13, Thm. 2.7.2.

In the notation of dependent pairs (here) this reads:

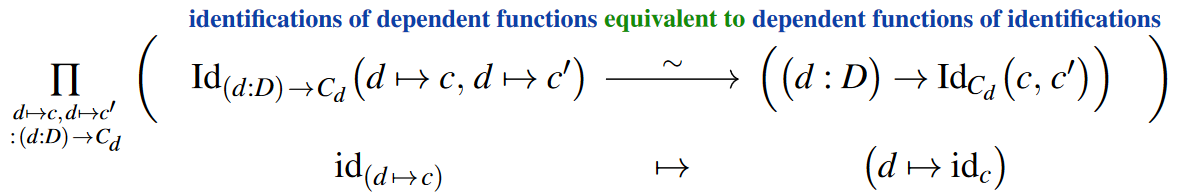

Compare to the analogous extensionality principle for dependent functions (see at function extensionality, here):

(In this dependent generality this is a special case of UFP13, Lem. 2.9.7.)

In lambda-calculus

The presentation of dependent sum type is almost exactly the same as that of product types, with the simple change that may depend on . In particular, they can be presented both as a negative type or as a positive type. In both cases, the rule for building the dependent sum type is the same:

but the constructors and eliminators may be different.

As a negative type

When presented negatively, primacy is given to the eliminators. We specify that there are two ways to eliminate a term of type : by projecting out the first component, or by projecting out the second.

This then determines the form of the constructors: in order to construct a term of type , we have to specify what value that term should yield when all the eliminators are applied to it. In other words, we have to specify a pair of elements, one (to be the value of ) and one (to be the value of ).

Finally, we have computation rules which say that the relationship between the constructors and the eliminators is as we hoped. We always have beta reduction rules

and we may or may not choose to have an eta reduction rule

As a positive type

When presented positively, primacy is given to the constructors. We specify that the way to construct something of type is to give a term and a term :

Of course, this is the same as the constructor obtained from the negative presentation. However, the eliminator is different. Now, in order to say how to use something of type , we have to specify how we should behave for all possible ways that it could have been constructed. In other words, we have to say, assuming that were of the form , what we want to do. Thus we end up with the following rule:

We need a term in the context of two variables of types and , and the destructor or match “binds those variables” to the two components of . Note that the “ordered pair” in the destructor is just a part of the syntax; it is not an instance of the constructor ordered pair.

Now we have the beta reduction rule:

In other words, if we build an ordered pair and then break it apart, what we get is just the things we put into it. (The notation means to substitute for and for in the term ).

And (if we wish) the eta reduction rule, which is a little more subtle:

This says that if we break something of type into its components, but then we only use those two components by way of putting them back together into an ordered pair, then we might as well just not have broken it down in the first place.

Positively defined dependent sum types are naturally expressed as inductive types. For instance, in Coq syntax we have

Inductive sig (A:Type) (B:A->Type) : Type :=

| exist : forall (x:A), B x -> sig A B.(Coq then implements beta-reduction, but not eta-reduction. However, eta-equivalence is provable with the internally defined identity type, using the dependent eliminator mentioned above.)

Arguably, negatively defined products should be naturally expressed as coinductive types, but this is not exactly the case for the presentation of coinductive types used in Coq.

Positive versus negative

In ordinary “nonlinear” type theory, the positive and negative dependent sum types are equivalent, just as in the case of product types. They manifestly have the same constructor, while we can define the eliminators in terms of each other as follows:

The computation rules then also correspond, just as for product types.

Also just as for product types, in order to recover the important dependent eliminator for the positive product type from the eliminators for the negative product type, we need the latter to satisfy the -conversion rule so as to make the above definition well-typed. By inserting a transport, we can make do with a propositional -conversion, which is also provable from the dependent eliminator.

One might expect that in “dependent linear type theory” the positive and negative dependent sums would become different. However, the meaning of the quoted phrase is unclear.

Using universes and dependent product types

Dependent sum types could be defined directly from universes, dependent product types, and function types - the last of which are definable from dependent product types. Given a type universe , the dependent sum type of the type family is defined as the dependent product type

This was the first definition of dependent sum types in dependent type theory, appearing in Per Martin-Löf‘s original 1971 paper on dependent type theory.

Properties

Descent and large elimination

The descent for the positive dependent sum type states that given any type family one can construct a type family with families of equivalences of types

Large elimination for positive dependent sum types strengthens the equivalences of types in descent to judgmental equality of types

Typal congruence rules

These are called typal congruence rules because they are the analogue of the judgmental congruence rules which use identity types and equivalence types instead of judgmental equality:

Theorem

Given types and and type families and and equivalences and dependent function of equivalences , there is an equivalence

Proof

This is theorem 11.1.6 of Rijke 2022, and a proof of this is given in that reference.

The typal congruence rules for dependent sum types are very important for proving various other theorems in dependent type theory. For example,

Theorem

Given a univalent Tarski universe and a -small type , the dependent sum type is contractible.

Proof

By univalence, for all and , transport across the universal type family is an equivalence of types

and thus we have the equivalence

and thus by the typal congruence rule of dependent sum types, we have

Since the type is contractible for all , the above equivalence implies that is also contractible.

Quantification in dependent type theory

Given a family of types , the existential quantifier is defined as the bracket type of the dependent sum type

The uniqueness quantifier is defined as the isContr modality of the dependent sum type

There is also a quantifier which states that holds for at most one element , defined by the isProp modality of the dependent sum type:

In each of the last two cases, one could prove that each dependent type has to be a mere proposition.

Given a natural number and given a family of types , we can similarly write down quantifiers to say that

- holds for exactly elements:

- holds for at most elements:

- holds for at least elements:

where is the equivalence type between and , is the type of embeddings between and , and is the finite set with elements.

Categorical interpretation

Under categorical semantics, a dependent type corresponds to a fibration or display map . In this case, the dependent sum is just the object . This requires the dependent sum type to satisfy both - and -conversion.

There is also another interpretation in category theory of the dependent sum type over as the initial -indexed wide cospan over , the object with a family of morphisms

such that for any other object with a family of morphisms , there exists a unique morphism such that

This corresponds to the positive dependent sum types.

Related concepts

References

A textbook account could be found in section 4.6 of:

- Egbert Rijke, Introduction to Homotopy Type Theory, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, Cambridge University Press (arXiv:2212.11082)

Discussion in a context of homotopy type theory:

- Univalent Foundations Project, Homotopy Type Theory – Univalent Foundations of Mathematics (2013) [web, pdf]

For the definition of dependent sum types in terms of universes, dependent product types, and function types, see:

- Per Martin-Löf, A Theory of Types, unpublished note (1971) [pdf, pdf]

See also most references at dependent type theory.

Last revised on May 14, 2025 at 23:09:06. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.