nLab double category

Context

2-Category theory

Definitions

Transfors between 2-categories

Morphisms in 2-categories

Structures in 2-categories

Limits in 2-categories

Structures on 2-categories

Contents

- Definition

- Examples

- Weakenings

- Pseudo double categories

- Double bicategories

- Strictly unital weak double categories

- Cubical bicategories

- Unbiased composition and associativity

- Higher categories of double categories

- (Skew) closed structures on the category of double categories

- Model structures on the category of double categories

- Related pages

- References

Definition

A double category is an internal category in Cat. Similarly, a double groupoid is an internal groupoid in Grpd.

However, these definitions obscure the essential symmetry of the concepts. We think of a double category as having

- objects: the objects of

- vertical morphisms: the morphisms of

- horizontal morphisms: the objects of

- 2-morphisms or squares or 2-cells: the morphisms of .

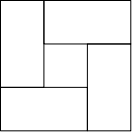

We may picture a 2-cell in a double category as a square:

Here are objects, and are horizontal arrows, are vertical arrows and is the 2-cell itself. This makes it clear why is called a ‘square’.

Alternatively one can apply Poincaré duality to obtain a string diagram representation for 2-cells, similar to the one obtained for 2-categories (Myers 16):

The vertical and horizontal arrows form categories (called edge categories), and the squares have two category structures which respect the edge category structures.

Vertical composition is given by the composition in the ordinary categories and , while horizontal composition is given by the composition operation specified on by virtue of it being a category internal to Cat.

In particular, the transpose of a double category, which switches the vertical and horizontal arrows, is again a double category.

A double category is an important special case of an n-fold category, namely the case where . There is more on -fold categories in the paper by Brown and Higgins referenced below.

Examples

-

If is a 2-category, there is its double category of squares whose objects are those of , both of whose types of morphisms are the morphisms in , and whose squares are 2-morphisms in with their source and target both decomposed as a composite of two morphisms. (These squares are sometimes called quintets where , and so this double category is said to be a quintet construction.)

(In this example, the two edge categories coincide. Double categories with this property are called edge-symmetric.)

-

Since any 1-category can be regarded as a 2-category with only identity 2-cells, for any 1-category we have a double category whose squares are the commutative squares in . We can also restrict the commutative squares considered, such as taking only pullback squares.

-

Any 2-category can also be made into a double category in two more ways, by defining the vertical or horizontal morphisms to consist only of identities. In this way 2-categories can be considered as a special case of double categories.

In the other direction, any double category has two underlying 2-categories, consisting of the objects, the vertical (resp. horizontal) arrows, and the squares whose horizontal-arrow (resp. vertical-arrow) source and target are identities. We call these its vertical 2-category and horizontal 2-category.

-

Finally, we can also make a 2-category into a double category with the same objects, whose horizontal arrows are the morphisms of , whose vertical arrows are the adjunctions in , and whose 2-cells are mate-pairs of 2-cells in . Naturality properties of the mate correspondence are concisely expressed by the existence of this double category.

-

There is a double category whose objects are (small) categories, whose vertical arrows are functors, whose horizontal arrows are profunctors, and whose squares are natural transformations. This double category is in fact an equipment, as are many other similar ones (such as for enriched categories).

-

Any topological space has a “homotopy double groupoid” whose objects are points, whose morphisms of both types are paths (so it is edge-symmetric), and whose 2-cells are homotopies.

-

There is a double category whose objects are monoidal categories, whose horizontal arrows are lax monoidal functors, whose vertical arrows are oplax monoidal functors, and whose 2-cells are generalized monoidal natural transformations. An analogous double category can be constructed involving the algebras for any 2-monad; see double category of algebras.

-

There is a double category of model categories whose objects are model categories, whose horizontal arrows are the right Quillen functors, vertical arrows the left Quillen functors, and whose 2-cells are arbitrary natural transformations. Passage to derived functors is a functor on this double category. More generally, we can define a double category of homotopical categories and “left derivable” and “right derivable” functors.

Weakenings

An internal category in the 1-category might more properly be called a strict double category, since all its composition operations are strictly associative and unital. Since a double category is a 2-dimensional structure, it makes sense to allow these compositions to be weak as well.

Pseudo double categories

A pseudo double category is a weakly internal category in the 2-category . Here “weakly internal category” in a 2-category is interpreted as being associative and unital up to coherent isomorphism, just as a bicategory is a “weakly enriched category.” This makes the composition in one direction weak, but the composition in the other direction remains strict (it is the composition in the objects of that make up the pseudo double category). Many naturally occurring examples, such as , are pseudo double categories.

In pseudo double categories, the vertical and horizontal morphisms are often called tight and loose morphisms, where the “tight” direction is strictly associative and unital, and the “loose” direction is only associative and unital up to isomorphism.

Luckily, every pseudo double category is equivalent to a double category of the usual sort, where composition of arrows in both directions is strictly associative. This is Theorem 7.5 of Grandis and Paré‘s paper Limits in double categories.

Double bicategories

One way to define a double category which is “weak in both directions” is a double bicategory. Double bicategories were defined in Dominic Verity‘s thesis. The definition can also be found in Jeffrey Morton’s paper Double bicategories and double cospans.

The definition of double bicategory takes as given two ordinary bicategories, representing the vertical and horizontal bicategories, together with a set of squares which is “acted on” by both of these. In the basic definition, there is no requirement that the 2-cells in the vertical (resp. horizontal) bicategory be exactly those squares whose vertical (resp. horizontal) 1-cell boundaries are identities, but such an axiom can easily be added.

The reason for stipulating the vertical and horizontal bicategories as a basic part of the structure is that if identities are strict in neither direction, then the vertically (resp. horizontally) “globular” 2-cells (those whose vertical or horizontal boundaries are identities) can’t seemingly be composed vertically (resp. horizontally), so it’s hard to state coherence axioms for the associativity and unit constraints.

Strictly unital weak double categories

Another way around this difficulty is to require the units to be strict, but not the associativity. This is not such a terrible thing, since units can usually be strictified much more easily than associativity. Thus, in this approach we assume as given

- a set of objects,

- two sets of vertical and horizontal arrows, equipped with identities and strictly unital (but not associative) composition operations,

- a set of squares, equipped with identities and strictly unital composition in both directions, and

- two sets of associativity squares, one with identity vertical boundary and one with identity horizontal boundary, satisfying the usual axioms, which are possible to state since identities are strict.

Cubical bicategories

Yet another approach to doubly-weak double categories was proposed by Richard Garner in an email to the categories list on 5 Mar 2010, in response to a query of Ronnie Brown. This approach avoids the coherence problems by being completely “unbiased.”

A cubical bicategory is given by sets of objects, of vertical arrows, of horizontal arrows and of squares, satisfying the obvious source and target criteria, together with operations of identity and binary composition for vertical and horizontal arrows, satisfying no laws at all; and finally, for every grid of squares (where possibly or are zero), and every way of composing up the horizontal and vertical boundaries using the nullary and binary compositions, a composite square with those boundaries. The coherence axioms which this structure must satisfy say that any two ways of composing up a diagram of squares must give the same answer.

He then commented:

I would be very interested to know if anyone can extract from this definition a finite collection of composition operations on squares, and a finite collection of equations between them, which together generate all the others. The key obstable seems to be problem that identity 1-cells are not strict in either direction.

It also seems that a “cubical bicategory” in this sense need not have underlying horizontal or vertical bicategories, for the same reason. This presents something of an obstacle to practical applications.

Unbiased composition and associativity

It is natural to ask what the “unbiased” notion of composition and associativity is for squares in a double category. The natural thing to take as input for an “unbiased composition” is a dissection of a rectangle into smaller rectangles, the smaller rectangles representing squares that we want to “compose up” in a double category. As usual, we can try to build up such a composite by means of the “biased” binary composites that are given in the definition of double category.

It can be shown that if a given such dissection can be composed up in some way using binary composites, then any two ways to compose it up must give the same result. See

- Dawson and Paré, General associativity and general composition for double categories , link

Also of interest is “Characterizing tileorders” by the same authors, in which they characterize such rectangle-dissections, called tileorders, in purely combinatorial terms.

However, there are dissections which admit no composition in a general double category, foremost among which is the “pinwheel:”

It is shown in the paper

- Dawson, A forbidden-suborder characterization of binarily-composable diagrams in double categories , TAC

that this is the only obstacle in the same sense that and are the only obstacles to planarity of a graph. Namely, if a diagram is not composable in a double category, then every “attempt” to compose it by a sequence of binary compositions will eventually result in a diagram which “contains” a pinwheel in a suitable sense (specifically, as a sub-tileorder).

In many double categories, however, arbitrary arrangements of squares, even pinwheels, can be composed. By this we mean that given a pinwheel diagram in such a double category (for example), there is a natural square with the same boundary which it makes sense to regard as “the composite” of that pinwheel. For example:

-

In the double category of squares/quintets in a 2-category, the general pasting theorem for 2-categories shows that any arrangement of squares can be composed. In particular, this applies to commutative squares in a 1-category. The same is true for double categories of adjunctions.

-

If all the squares in a pinwheel are pullback squares in a 1-category, so is the whole thing. The same is true for more general arrangements in a double category of pullback squares.

-

Arbitrary arrangements can also be composed in and its variants, again by the pasting theorem for 2-categories, since its 2-cells are just ordinary natural transformations.

-

Pinwheels and more general arrangements can also be composed in the double category , along with its relatives . The proof of this is not quite as trivial, but fairly straightforward.

-

In any fibrant double category, all arrangements can be composed.

This last example is due to a factorization property: if we can factor the two long vertical rectangles in the pinwheel into two squares, then we can compose it. The cartesian cells in a fibrant double category certainly allow such a factorization. One can also axiomatize more precisely what factorization properties are necessary; this is done in the above paper of Dawson and Paré.

In fact, it seems hard to find a naturally occurring double category in which pinwheels and more general arranguments cannot be composed, although such composability definitely does not follow from the double-category axioms. This suggests that perhaps the usual definition of double category is too naive, and we should actually require all “unbiased” composites to exist, including the pinwheel. There is probably a monad of some sort on a suitable category whose algebras are “double categories with generalized composites” in this sense.

(It is tempting to try to axiomatize such a structure finitely by adding a basic “pinwheel-composition” operation, but although every non-composable arrangement reduces to one “containing” a pinwheel, the containment is not necessarily of a sort to which such an operation could be applied. For example, here is a configuration that cannot be composed even with a “pinwheel-composition” operation:

Thus, it is not clear whether there is any finitary axiomatization of such “augmented” double categories.)

Higher categories of double categories

There are notions of functor and of transformation between double categories, which make them into a 2-category. In fact, due to the vertical-horizontal symmetry, there are two such 2-categories, depending on the direction we choose the transformations to go in. Moreover, we can also take the functors to be strict, pseudo, lax, or oplax in either direction, so there are many possible 2-categories of double categories (although for some choices one has to worry about compatibility).

Probably the most useful such 2-categories are where we choose one direction to be the “arrow” direction and the other the “proarrow” direction, we take functors which are lax, oplax, or pseudo in the proarrow direction and strict in the arrow direction, and transformations that go in the arrow direction. This is natural when considering double categories such as proarrow equipments. If we allow the functors and transformations to be only pseudo in the arrow direction as well, and add in modifications in the arrow direction, we obtain a 3-category instead. In some situations, such as the study of generalized multicategories, this 3-category is a natural place in which to work (or an enlargement of it to include virtual equipments as well).

We can also combine the horizontally lax and oplax functors, together with a general notion of vertical transformation, into a large double category of double categories. This is a special case of the double category of -algebras for a particular 2-monad mentioned above; see double category of algebras.

In some contexts, a natural observation is that the 1-category is cartesian closed, and thus enriched over itself–thus it forms a locally double bicategory?, i.e. a category enriched over double categories. This can be regaded as a structure like a 3-category, except that it has two different kinds of 2-cells (in this case, the vertical and horizontal transformations).

In any of these higher categories, we can apply the notions and methods of higher category theory. For instance, we automatically obtain a notion of monoidal double category, namely a pseudomonoid in . Likewise we have cartesian double categories, which are cartesian objects in . If the double category in question is fibrant, then monoidal structures can be lifted to the horizontal bicategory; many naturally occurring cartesian bicategories can be obtained in this way.

Finally, if we want to discuss weighted limits and colimits in double categories, or construct generalized multicategories based on double categories, we may want to equip DblCat with proarrows. There is a notion of double profunctor, but they do not compose associatively, and hence do not form a proarrow equipment in the usual sense; but they do form a virtual equipment, which is sufficient for many purposes.

(Skew) closed structures on the category of double categories

| Category | Internal hom | Monoidal | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strict double categories, strict functors | Strict functors, strict vertical and horizontal transformations, modifications | Yes | Cartesian | Follows from the theory of internal categories |

| Strict double categories, strict functors | Strict functors, pseudo vertical and horizontal transformations, modifications | Yes | Symmetric | Campbell19, Böhm20 |

| Pseudo double categories, strict functors | Pseudo functors, tight transformations, pseudo loose transformations, modifications | No | Symmetric skew | Campbell19 |

| Pseudo double categories, pseudo functors | Pseudo functors, tight transformations, pseudo loose transformations, modifications | Bicategorically cartesian monoidal | Symmetric | Campbell19, §2 of Garner06 |

| Strict double categories, strict functors | Strict functors, oplax horizontal, lax vertical, modifications | Yes | Theorem 4.2 of Femić24 | |

| Strict double categories, strict functors | Pseudo/lax/oplax functors, pseudo/lax/oplax horizontal, dually for vertical, modifications | Yes | Skew | §6.4.2 of Femić24 |

References

-

Gabriella Böhm, The Gray monoidal product of double categories, Applied Categorical Structures 28.3 (2020): 477-515.

-

Alexander Campbell, How strict is strictification?, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra 223.7 (2019): 2948-2976.

An exploration of the possibility of a closed structure on strict double categories and lax functors may be found in:

- Bojana Femić?, Bifunctor Theorem and strictification tensor product for double categories with lax double functors, arXiv:2207.13452 (2022).

Skew monoidal structures are constructed on categories of double categories in:

- Bojana Femić?, Gray (skew) multicategories: double and Gray-categorical cases, arXiv:2408.00561 (2024).

Model structures on the category of double categories

The category of strict double categories admits a plethora of Quillen model structures, some of which are described in papers by Fiore, Paoli, and Pronk, Fiore and Paoli, Moser, Sarazola, and Verdugo I and Moser, Sarazola, and Verdugo II and Campbell.

For more see model structure on DblCat.

Gregarious model structure

The gregarious model structure on the category of double categories is defined uniquely by the following two properties:

- Every double category is fibrant.

- A double functor is a trivial fibration if it is surjective on objects, full on horizontal morphisms, full on vertical morphisms, and fully faithful on double cells.

Weak equivalences in this model structure can be characterized as follows. A double functor is a weak equivalence in the gregarious model structure for double categories if and only if it satisfies the following four conditions.

- is surjective on objects up to gregarious equivalence, meaning that for every object there is an object and a gregarious equivalence in ;

- is full on horizontal morphisms up to globular isomorphism;

- is full on vertical morphisms up to globular isomorphism;

- is fully faithful on double cells.

Here a globular isomorphism is an invertible 2-cell in the horizontal respectively vertical 2-category associated to the given double category .

A gregarious equivalence is a companion pair of morphisms in such that is an equivalence in the horizontal 2-category of and is an equivalence in the vertical 2-category of .

Related pages

-

monoidal double category, locally double bicategory?

References

The concept goes back to:

-

Charles Ehresmann, Catégories double et catégories structurées, C.R. Acad. Paris 256 (1963) 1198-1201 [pdf, gallica]

-

Charles Ehresmann, Déf. 10, p. 389 in: Catégories structurées, Annales scientifiques de l’École Normale Supérieure. Vol. 80. No. 4. Elsevier, 1963 [eudml:81794]

For a comprehensive treatment, it is probably best to consult the series of papers by Grandis and Paré:

-

Marco Grandis and Robert Paré, Limits in double categories, Cahiers de Topologie et Géométrie Différentielle Catégoriques 40 (1999), 162–220.

-

Marco Grandis and Robert Paré, Adjoints for double categories, Cahiers de Topologie et Géométrie Différentielle Catégoriques 45 (2004), 193–240.

-

Marco Grandis and Robert Paré, Kan extensions in double categories (On weak double categories, Part III), Theory and Applications of Categories, Vol. 20, 2008, No. 8, pp 152-185.

-

Marco Grandis and Robert Paré, Lax Kan extensions for double categories (On weak double categories, Part IV) Cahiers de topologie et géométrie différentielle catégoriques, tome 48, no 3 (2007), p. 163-199

For basic theory of the (virtual) double category of presheaves on a double category, the Yoneda embedding, and the density theorem

-

Robert Paré Yoneda theory for double categories, Theory and Applications of Categories, Vol. 25, 2011, No. 17, pp 436-489.

-

Robert Paré Composition of Modules for Lax Functors, Theory and Applications of Categories, Vol. 27, 2013, No. 16, pp 393-444.

Textbook accounts:

-

Niles Johnson, Donald Yau, Section 12.3 of: 2-Dimensional Categories, Oxford University Press 2021 (arXiv:2002.06055, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198871378.001.0001)

-

Marco Grandis, Higher dimensional categories: from double to multiple categories, World Scientific, 2019. (doi:10.1142/11406)

See also:

-

The Catsters, Double Categories (YouTube).

-

Tom Fiore, Double categories and pseudo algebras.

-

Jeffrey C. Morton, Double bicategories and double cospans.

-

Ronnie Brown and C.B. Spencer, Double groupoids and crossed modules, Cahiers de Topologie et Géométrie Différentielle Catégoriques 17 (1976), 343–362.

-

Ronnie Brown and Philip Higgins, The equivalence of -groupoids and crossed complexes, Cah. Top. Géom. Diff. 22 (1981) 371-386.

-

Mike Shulman, Comparing composites of left and right derived functors, New York J. Math. 17 (2011) 75–125. arXiv:0706.2868

-

David Jaz Myers, String diagrams for double categories and (virtual) equipments (arXiv:1612.02762)

-

Kenny Courser, Open systems: a double categorical perspective, PhD thesis, arxiv/2008.02394

-

Antonin Delpeuch, The word problem for double categories, arxiv

-

Virtual Double Categories Workshop, 2022 (webpage)

-

Second Virtual Workshop on Double Categories, 2024 (webpage)

On model structures on DblCat:

-

Thomas M. Fiore, Simona Paoli, Dorette A. Pronk, Model structures on the category of small double categories, Algebraic & Geometric Topology 8 (2008) 1855–1959 [doi:10.2140/agt.2008.8.1855]

-

Thomas Fiore, Simona Paoli, A Thomason model structure on the category of small -fold categoriesAlgebraic & Geometric Topology 10 (2010) 1933–2008 [doi:10.2140/agt.2010.10.1933]

-

Lyne Moser, Maru Sarazola, Paula Verdugo, A -inspired model structure for double categories, Cahiers de Topologie et Géométrie Différentielle Catégoriques, LXIII2 (2022) [arxiv:2004.14233, journal:pdf]

-

Alexander Campbell, The gregarious model structure for double categories (2020) [talk slides pdf]

-

Lyne Moser, Maru Sarazola, Paula Verdugo, A model structure for weakly horizontally invariant double categories, Algebraic & Geometric Topology 23 4 (2023) 1725-1786 [arxiv:2007.00588, journal:pdf]

For the (bicategorically) cartesian closed structure, see:

- Richard Garner, Double clubs, Cahiers de Topologie et Geometrie Differentielle Categoriques 47 (2006), no. 4, 261–317; arXiv

An explicit description of what it means to be a one-object double category (i.e. filling in the gap in “a delooping of a ___ is a double category”) is given in this Math.StackExchange answer.

For univalent double categories? in dependent type theory:

- Niels van der Weide, Nima Rasekh, Benedikt Ahrens, Paige Randall North, Univalent Double Categories [arXiv:2310.09220]

Last revised on June 9, 2025 at 16:27:12. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.