nLab A first idea of quantum field theory -- Fields

Fields

In this chapter we discuss these topics:

A field history on a given spacetime (a history of spatial field configurations, see remark below) is a quantity assigned to each point of spacetime (each event), such that this assignment varies smoothly with spacetime points. For instance an electromagnetic field history (example below) is at each point of spacetime a collection of vectors that encode the direction in which a charged particle passing through that point would feel a force (the “Lorentz force”, see example below).

This is readily formalized (def. below): If denotes the smooth manifold of “values” that the given kind of field may take at any spacetime point, then a field history is modeled as a smooth function from spacetime to this space of values:

It will be useful to unify spacetime and the space of field values (the field fiber) into a single manifold, the Cartesian product

and to think of this equipped with the projection map onto the first factor as a fiber bundle of spaces of field values over spacetime

This is then called the field bundle, which specifies the kind of values that the given field species may take at any point of spacetime. Since the space of field values is the fiber of this fiber bundle (def. ), it is sometimes also called the field fiber. (See also at fiber bundles in physics.)

Given a field bundle , then a field history is a section of that bundle (def. ). The discussion of field theory concerns the space of all possible field histories, hence the space of sections of the field bundle (example below). This is a very “large” generalized smooth space, called a diffeological space (def. below).

Or rather, in the presence of fermion fields such as the Dirac field (example below), the Pauli exclusion principle demands that the field bundle is a super-manifold, and that the fermionic space of field histories (example below) is a super-geometric generalized smooth space: a super smooth set (def. below).

This smooth structure on the space of field histories will be crucial when we discuss observables of a field theory below, because these are smooth functions on the space of field histories. In particular it is this smooth structure which allows to derive that linear observables of a free field theory are given by distributions (prop. ) below. Among these are the point evaluation observables (delta distributions) which are traditionally denoted by the same symbol as the field histories themselves.

Hence there are these aspects of the concept of “field” in physics, which are closely related, but crucially different:

aspects of the concept of fields

| aspect | term | type | description | def. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| field component | , | coordinate function on jet bundle of field bundle | def. , def. | |

| field history | , | jet prolongation of section of field bundle | def. , def. | |

| field observable | , | derivatives of delta-functional on space of sections | def. , example | |

| averaging of field observable | observable-valued distribution | def. | ||

| algebra of quantum observables | non-commutative algebra structure on field observables | def. , def. |

Definition

(fields and field histories)

Given a spacetime , then a type of fields on is a smooth fiber bundle (def. )

called the field bundle,

Given a type of fields on this way, then a field history of that type on is a term of that type, hence is a smooth section (def. ) of this bundle, namely a smooth function of the form

such that composed with the projection map it is the identity function, i.e. such that

The set of such sections/field histories is to be denoted

Remark

(field histories are histories of spatial field configurations)

Given a section of the field bundle (def. ) and given a spacelike (def. ) submanifold (def. ) of spacetime in codimension 1, then the restriction of to may be thought of as a field configuration in space. As different spatial slices are chosen, one obtains such field configurations at different times. It is in this sense that the entirety of a section is a history of field configurations, hence a field history (def ).

Remark

(possible field histories)

After we give the set of field histories (1) differential geometric structure, below in example and example , we call it the space of field histories. This should be read as space of possible field histories; containing all field histories that qualify as being of the type specified by the field bundle .

After we obtain equations of motion below in def. , these serve as the “laws of nature” that field histories should obey, and they define the subspace of those field histories that do solve the equations of motion; this will be denoted

and called the on-shell space of field histories (?).

For the time being, not to get distracted from the basic idea of quantum field theory, we will focus on the following simple special case of field bundles:

Example

(trivial vector bundle as a field bundle)

In applications the field fiber is often a finite dimensional vector space. In this case the trivial field bundle with fiber is of course a trivial vector bundle (def. ).

Choosing any linear basis of the field fiber, then over Minkowski spacetime (def. ) we have canonical coordinates on the total space of the field bundle

where the index ranges from to , while the index ranges from 1 to .

If this trivial vector bundle is regarded as a field bundle according to def. , then a field history is equivalently an -tuple of real-valued smooth functions on spacetime:

Example

(field bundle for real scalar field)

If is a spacetime and if the field fiber

is simply the real line, then the corresponding trivial field bundle (def. )

is the trivial real line bundle (a special case of example ) and the corresponding field type (def. ) is called the real scalar field on . A configuration of this field is simply a smooth function on with values in the real numbers:

Example

(field bundle for electromagnetic field)

On Minkowski spacetime (def. ), let the field bundle (def. ) be given by the cotangent bundle

This is a trivial vector bundle (example ) with canonical field coordinates .

A section of this bundle, hence a field history, is a differential 1-form

on spacetime (def. ). Interpreted as a field history of the electromagnetic field on , this is often called the vector potential. Then the de Rham differential (def. ) of the vector potential is a differential 2-form

known as the Faraday tensor. In the canonical coordinate basis 2-forms this may be expanded as

Here are called the components of the electric field, while are called the components of the magnetic field.

Example

(field bundle for Yang-Mills field over Minkowski spacetime)

Let be a Lie algebra of finite dimension with linear basis , in terms of which the Lie bracket is given by

Over Minkowski spacetime (def. ), consider then the field bundle which is the cotangent bundle tensored with the Lie algebra

This is the trivial vector bundle (example ) with induced field coordinates

A section of this bundle is a Lie algebra-valued differential 1-form

with components

This is called a field history for Yang-Mills gauge theory (at least if is a semisimple Lie algebra, see example below).

For is the line Lie algebra, this reduces to the case of the electromagnetic field (example ).

For this is a field history for the gauge field of the strong nuclear force in quantum chromodynamics.

For readers familiar with the concepts of principal bundles and connections on a bundle we include the following example which generalizes the Yang-Mills field over Minkowski spacetime from example to the situation over general spacetimes.

Example

(general Yang-Mills field in fixed topological sector)

Let be any spacetime manifold and let be a compact Lie group with Lie algebra denoted . Let be a -principal bundle and a chosen connection on it, to be called the background -Yang-Mills field.

Then the field bundle (def. ) for -Yang-Mills theory in the topological sector is the tensor product of vector bundles

of the adjoint bundle of and the cotangent bundle of .

With the choice of , every (other) connection on uniquely decomposes as

where

is a section of the above field bundle, hence a Yang-Mills field history.

The electromagnetic field (def. ) and the Yang-Mills field (def. , def. ) with differential 1-forms as field histories are the basic examples of gauge fields (we consider this in more detail below in Gauge symmetries). There are also higher gauge fields with differential n-forms as field histories:

Example

(field bundle for B-field)

On Minkowski spacetime (def. ), let the field bundle (def. ) be given by the skew-symmetrized tensor product of vector bundles of the cotangent bundle with itself

This is a trivial vector bundle (example ) with canonical field coordinates subject to

A section of this bundle, hence a field history, is a differential 2-form (def. )

on spacetime.

Given any field bundle, we will eventually need to regard the set of all field histories as a “smooth set” itself, a smooth space of sections, to which constructions of differential geometry apply (such as for the discussion of observables and states below ). Notably we need to be talking about differential forms on .

However, a space of sections does not in general carry the structure of a smooth manifold; and it carries the correct smooth structure of an infinite dimensional manifold only if is a compact space (see at manifold structure of mapping spaces). Even if it does carry infinite dimensional manifold structure, inspection shows that this is more structure than actually needed for the discussion of field theory. Namely it turns out below that all we need to know is what counts as a smooth family of sections/field histories, hence which functions of sets

from any Cartesian space (def. ) into count as smooth functions, subject to some basic consistency condition on this choice.

This structure on is called the structure of a diffeological space:

Definition

A diffeological space is

-

for each a choice of subset

of the set of functions from the underlying set of to , to be called the smooth functions or plots from to ;

-

for each smooth function between Cartesian spaces (def. ) a choice of function

to be thought of as the precomposition operation

such that

-

(constant functions are smooth)

-

-

If is the identity function on , then is the identity function on the set of plots ;

-

If are two composable smooth functions between Cartesian spaces (def. ), then pullback of plots along them consecutively equals the pullback along the composition:

i.e.

-

-

(gluing)

If is a differentiably good open cover of a Cartesian space (def. ) then the function which restricts -plots of to a set of -plots

is a bijection onto the set of those tuples of plots, which are “matching families” in that they agree on intersections:

Finally, given and two diffeological spaces, then a smooth function between them

is

-

a function of the underlying sets

such that

-

for a plot of , then the composition is a plot of :

(Stated more abstractly, this says simply that diffeological spaces are the concrete sheaves on the site of Cartesian spaces from def. .)

For more background on diffeological spaces see also geometry of physics – smooth sets.

Example

(Cartesian spaces are diffeological spaces)

Let be a Cartesian space (def. ) Then it becomes a diffeological space (def. ) by declaring its plots to the ordinary smooth functions .

Under this identification, a function between the underlying sets of two Cartesian spaces is a smooth function in the ordinary sense precisely if it is a smooth function in the sense of diffeological spaces.

Stated more abstractly, this statement is an example of the Yoneda embedding over a subcanonical site.

More generally, the same construction makes every smooth manifold a smooth set.

Example

(diffeological space of field histories)

Let be a smooth field bundle (def. ). Then the set of field histories/sections (def. ) becomes a diffeological space (def. )

by declaring that a smooth family of field histories, parameterized over any Cartesian space is a smooth function out of the Cartesian product manifold of with

such that for each we have , i.e.

The following example is included only for readers who wonder how infinite-dimensional manifolds fit in. Since we will never actually use infinite-dimensional manifold-structure, this example is may be ignored.

Example

(Fréchet manifolds are diffeological spaces)

Consider the particular type of infinite-dimensional manifolds called Fréchet manifolds. Since ordinary smooth manifolds are an example, for a Fréchet manifold there is a concept of smooth functions . Hence we may give the structure of a diffeological space (def. ) by declaring the plots over to be these smooth functions , with the evident postcomposition action.

It turns out that then that for and two Fréchet manifolds, there is a natural bijection between the smooth functions between them regarded as Fréchet manifolds and [regarded as . Hence it does not matter which of the two perspectives we take (unless of course a more general than a enters the picture, at which point the second definition generalizes, whereas the first does not).]

Stated more abstractly, this means that Fréchet manifolds form a full subcategory of that of diffeological spaces (this prop.):

If is a compact smooth manifold and is a trivial fiber bundle with fiber a smooth manifold, then the set of sections carries a standard structure of a Fréchet manifold (see at manifold structure of mapping spaces). Under the above inclusion of Fréchet manifolds into diffeological spaces, this smooth structure agrees with that from example (see this prop.)

Once the step from smooth manifolds to diffeological spaces (def. ) is made, characterizing the smooth structure of the space entirely by how we may probe it by mapping smooth Cartesian spaces into it, it becomes clear that the underlying set of a diffeological space is not actually crucial to support the concept: The space is already entirely defined structurally by the system of smooth plots it has, and the underlying set is recovered from these as the set of plots from the point .

This is crucial for field theory: the spaces of field histories of fermionic fields (def. below) such as the Dirac field (example below) do not have underlying sets of points the way diffeological spaces have. Informally, the reason is that a point is a bosonic object, while and the nature of fermionic fields is the opposite of bosonic.

But we may just as well drop the mentioning of the underlying set in the definition of generalized smooth spaces. By simply stripping this requirement off of def. we obtain the following more general and more useful definition (still “bosonic”, though, the supergeometric version is def. below):

Definition

A smooth set is

-

for each a choice of set

to be called the set of smooth functions or plots from to ;

-

for each smooth function between Cartesian spaces a choice of function

to be thought of as the precomposition operation

such that

-

-

If is the identity function on , then is the identity function on the set of plots .

-

If are two composable smooth functions between Cartesian spaces, then consecutive pullback of plots along them equals the pullback along the composition:

i.e.

-

-

(gluing)

If is a differentiably good open cover of a Cartesian space (def. ) then the function which restricts -plots of to a set of -plots

is a bijection onto the set of those tuples of plots, which are “matching families” in that they agree on intersections:

Finally, given and two smooth sets, then a smooth function between them

is

-

for each a function

such that

-

for each smooth function between Cartesian spaces we have

Stated more abstractly, this simply says that smooth sets are the sheaves on the site of Cartesian spaces from def. .

Basing differential geometry on smooth sets is an instance of the general approach to geometry called functorial geometry or topos theory. For more background on this see at geometry of physics – smooth sets.

First we verify that the concept of smooth sets is a consistent generalization:

Example

(diffeological spaces are smooth sets)

Every diffeological space (def. ) is a smooth set (def. ) simply by forgetting its underlying set of points and remembering only its sets of plot.

In particular therefore each Cartesian space is canonically a smooth set by example .

Moreover, given any two diffeological spaces, then the morphisms between them, regarded as diffeological spaces, are the same as the morphisms as smooth sets.

Stated more abstractly, this means that we have full subcategory inclusions

Recall, for the next proposition , that in the definition of a smooth set the sets are abstract sets which are to be thought of as would-be smooth functions “”. Inside def. this only makes sense in quotation marks, since inside that definition the smooth set is only being defined, so that inside that definition there is not yet an actual concept of smooth functions of the form “”.

But now that the definition of smooth sets and of morphisms between them has been stated, and seeing that Cartesian space are examples of smooth sets, by example , there is now an actual concept of smooth functions , namely as smooth sets. For the concept of smooth sets to be consistent, it ought to be true that this a posteriori concept of smooth functions from Cartesian spaces to smooth sets coincides wth the a priori concept, hence that we “may remove the quotation marks” in the above. The following proposition says that this is indeed the case:

Proposition

(plots of a smooth set really are the smooth functions into the smooth set)

Let be a smooth set (def. ). For , there is a natural function

from the set of homomorphisms of smooth sets from (regarded as a smooth set via example ) to , to the set of plots of over , given by evaluating on the identity plot .

This function is a bijection.

This says that the plots of , which initially bootstrap into being as declaring the would-be smooth functions into , end up being the actual smooth functions into .

Proof

This elementary but profound fact is called the Yoneda lemma, here in its incarnation over the site of Cartesian spaces (def. ).

A key class of examples of smooth sets (def. ) that are not diffeological spaces (def. ) are universal smooth moduli spaces of differential forms:

Example

(universal smooth moduli spaces of differential forms)

For there is a smooth set (def. )

defined as follows:

-

for the set of plots from to is the set of smooth differential k-forms on (def. )

-

for a smooth function (def. ) the operation of pullback of plots along is just the pullback of differential forms from prop.

That this is functorial is just the standard fact (?) from prop. .

For the smooth set actually is a diffeological space, in fact under the identification of example this is just the real line:

But for we have that the set of plots on is a singleton

consisting just of the zero differential form. The only diffeological space with this property is itself. But is far from being that trivial: even though its would-be underlying set is a single point, for all it admits an infinite set of plots. Therefore the smooth sets for are not diffeological spaces.

That the smooth set indeed deserves to be addressed as the universal moduli space of differential k-forms follows from prop. : The universal moduli space of -forms ought to carry a universal differential -forms such that every differential -form on any arises as the pullback of differential forms of this universal one along some modulating morphism :

But with prop. this is precisely what the definition of the plots of says.

Similarly, all the usual operations on differential form now have their universal archetype on the universal moduli spaces of differential forms

In particular, for there is a canonical morphism of smooth sets of the form

defined over by the ordinary de Rham differential (def. )

That this satisfies the compatibility with precomposition of plots

is just the compatibility of pullback of differential forms with the de Rham differential of from prop. .

The upshot is that we now have a good definition of differential forms on any diffeological space and more generally on any smooth set:

Definition

(differential forms on smooth sets)

Let be a diffeological space (def. ) or more generally a smooth set (def. ) then a differential k-form on is equivalently a morphism of smooth sets

from to the universal smooth moduli space of differential froms from example .

Concretely, by unwinding the definitions of and of morphisms of smooth sets, this means that such a differential form is:

-

for each and each plot an ordinary differential form

such that

-

for each smooth function between Cartesian spaces the ordinary pullback of differential forms along is compatible with these choices, in that for every plot we have

i.e.

We write for the set of differential forms on the smooth set defined this way.

Moreover, given a differential k-form

on a smooth set this way, then its de Rham differential is given by the composite of morphisms of smooth sets with the universal de Rham differential from (6):

Explicitly this means simply that for a plot, then

The usual operations on ordinary differential forms directly generalize plot-wise to differential forms on diffeological spaces and more generally on smooth sets:

Definition

(exterior differential and exterior product on smooth sets)

Let be a diffeological space (def. ) or more generally a smooth set (def. ). Then

-

For a differential form on (def. ) its exterior differential

is defined on any plot as the ordinary exterior differential of the pullback of along that plot:

-

For and two differential forms on (def. ) then their exterior product

is the differential form defined on any plot as the ordinary exterior product of the pullback of th differential forms and to this plot:

Infinitesimal geometry

It is crucial in field theory that we consider field histories not only over all of spacetime, but also restricted to submanifolds of spacetime. Or rather, what is actually of interest are the restrictions of the field histories to the infinitesimal neighbourhoods (example below) of these submanifolds. This appears notably in the construction of phase spaces below. Moreover, fermion fields such as the Dirac field (example below) take values in graded infinitesimal spaces, called super spaces (discussed below). Therefore “infinitesimal geometry”, sometimes called formal geometry (as in “formal scheme”) or synthetic differential geometry or synthetic differential supergeometry, is a central aspect of field theory.

In order to mathematically grasp what infinitesimal neighbourhoods are, we appeal to the first magic algebraic property of differential geometry from prop. , which says that we may recognize smooth manifolds dually in terms of their commutative algebras of smooth functions on them

But since there are of course more algebras than arise this way from smooth manifolds, we may turn this around and try to regard any algebra as defining a would-be space, which would have as its algebra of functions.

For example an infinitesimally thickened point should be a space which is “so small” that every smooth function on it which vanishes at the origin takes values so tiny that some finite power of them is not just even more tiny, but actually vanishes:

Definition

(infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space)

An infinitesimally thickened point

is represented by a commutative algebra which as a real vector space is a direct sum

of the 1-dimensional space of multiples of 1 with a finite dimensional vector space that is a nilpotent ideal in that for each element there exists a natural number such that

More generally, an infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space

is represented by a commutative algebra

which is the tensor product of algebras of the algebra of smooth functions on an actual Cartesian space of some dimension (example ), with an algebra of functions of an infinitesimally thickened point, as above.

We say that a smooth function between two infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces

is by definition dually an -algebra homomorphism of the form

Example

(infinitesimal neighbourhoods in the real line )

Consider the quotient algebra of the formal power series algebra in a single parameter by the ideal generated by :

(This is sometimes called the algebra of dual numbers, for no good reason.) The underlying real vector space of this algebra is, as show, the direct sum of the multiples of 1 with the multiples of . A general element in this algebra is of the form

where are real numbers. The product in this algebra is given by “multiplying out” as usual, and discarding all terms proportional to :

We may think of an element as the truncation to first order of a Taylor series at the origin of a smooth function on the real line

where is the value of the function at the origin, and where is its first derivative at the origin.

Therefore this algebra behaves like the algebra of smooth function on an infinitesimal neighbourhood of which is so tiny that its elements become, upon squaring them, not just tinier, but actually zero:

This intuitive picture is now made precise by the concept of infinitesimally thickened points def. , if we simply set

and observe that there is the inclusion of infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces

which is dually given by the algebra homomorphism

which sends a smooth function to its value at zero plus times its derivative at zero. Observe that this is indeed a homomorphism of algebras due to the product law of differentiation, which says that

Hence we see that restricting a smooth function to the infinitesimal neighbourhood of a point is equivalent to restricting attention to its Taylor series to the given order at that point:

Similarly for each the algebra

may be thought of as the algebra of Taylor series at the origin of of smooth functions , where all terms of order higher than are discarded. The corresponding infinitesimally thickened point is often denoted

This is now the subobject of the real line

on those elements such that .

The following example shows that infinitesimal thickening is invisible for ordinary spaces when mapping out of these. In contrast example further below shows that the morphisms into an ordinary space out of an infinitesimal space are interesting: these are tangent vectors and their higher order infinitesimal analogs.

Example

(infinitesimal line has unique global point)

For any ordinary Cartesian space (def. ) and the order- infinitesimal neighbourhood of the origin in the real line from example , there is exactly only one possible morphism of infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces from to :

Proof

By definition such a morphism is dually an algebra homomorphism

from the higher order “algebra of dual numbers” to the algebra of smooth functions (example ).

Now this being an -algebra homomorphism, its action on the multiples of the identity is fixed:

All the remaining elements are proportional to , and hence are nilpotent. However, by the homomorphism property of an algebra homomorphism it follows that it must send nilpotent elements to nilpotent elements , because

But the only nilpotent element in is the zero element, and hence it follows that

Thus as above is uniquely fixed.

Example

(synthetic tangent vector fields)

Let be a Cartesian space (def. ), regarded as an infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space (def. ) and consider the first order infinitesimal line from example .

Then homomorphisms of infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces of the form

hence smoothly -parameterized collections of morphisms

which send the unique base point (example ) to , are in natural bijection with tangent vector fields (example ).

Proof

By definition, the morphisms in question are dually -algebra homomorphisms of the form

which are the identity modulo . Such a morphism has to take any function to

for some smooth function . The condition that this assignment makes an algebra homomorphism is equivalent to the statement that for all we have

Multiplying this out and using that , this is equivalent to

This in turn means equivalently that is a derivation.

With this the statement follows with the third magic algebraic property of smooth functions (prop. ): derivations of smooth functions are vector fields.

We need to consider infinitesimally thickened spaces more general than the thickenings of just Cartesian spaces in def. . But just as Cartesian spaces (def. ) serve as the local test geometries to induce the general concept of diffeological spaces and smooth sets (def. ), so using infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces as test geometries immediately induces the corresponding generalization of smooth sets with infinitesimals:

Definition

A formal smooth set is

-

for each infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space (def. ) a set

to be called the set of smooth functions or plots from to ;

-

for each smooth function between infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces a choice of function

to be thought of as the precomposition operation

such that

-

-

If is the identity function on , then is the identity function on the set of plots ;

-

If are two composable smooth functions between infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces, then pullback of plots along them consecutively equals the pullback along the composition:

i.e.

-

-

(gluing)

If is such that

in a differentiably good open cover (def. ) then the function which restricts -plots of to a set of -plots

is a bijection onto the set of those tuples of plots, which are “matching families” in that they agree on intersections:

i.e.

Finally, given and two formal smooth sets, then a smooth function between them

is

-

for each infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space (def. ) a function

such that

-

for each smooth function between infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces we have

i.e.

(Dubuc 79)

Basing infinitesimal geometry on formal smooth sets is an instance of the general approach to geometry called functorial geometry or topos theory. For more background on this see at geometry of physics – manifolds and orbifolds.

We have the evident generalization of example to smooth geometry with infinitesimals:

Example

(infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces are formal smooth sets)

For an infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space (def. ), it becomes a formal smooth set according to def. by taking its plots out of some to be the homomorphism of infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces:

(Stated more abstractly, this is an instance of the Yoneda embedding over a subcanonical site.)

Example

(smooth sets are formal smooth sets)

Let be a smooth set (def. ). Then becomes a formal smooth set (def. ) by declaring the set of plots over an infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space (def. ) to be equivalence classes of pairs

of a morphism of infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces and of a plot of , as shown, subject to the equivalence relation which identifies two such pairs if there exists a smooth function such that

Stated more abstractly this says that as a formal smooth set is the left Kan extension (see this example) of as a smooth set along the functor that includes Cartesian spaces (def. ) into infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces (def. ).

Definition

(reduction and infinitesimal shape)

For an infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space (def. ) we say that the underlying ordinary Cartesian space (def. ) is its reduction

There is the canonical inclusion morphism

which dually corresponds to the homomorphism of commutative algebras

which is the identity on all smooth functions and is zero on all elements in the nilpotent ideal of (as in example ).

Given any formal smooth set , we say that its infinitesimal shape or de Rham shape (also: de Rham stack) is the formal smooth set (def. ) defined to have as plots the reductions of the plots of , according to the above:

There is a canonical morphism of formal smooth set

which takes a plot

to the composition

regarded as a plot of .

Example

(mapping space out of an infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space)

Let be an infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space (def. ) and let be a formal smooth set (def. ). Then the mapping space

of smooth functions from to is the formal smooth set whose -plots are the morphisms of formal smooth sets from the Cartesian product of infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces to , hence the -plots of :

Example

Let be a Cartesian space (def. ) regarded as an infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space () and thus regarded as a formal smooth set (def. ) by example . Consider the infinitesimal line

from example . Then the mapping space (example ) is the total space of the tangent bundle (example ). Moreover, under restriction along the reduction , this is the full tangent bundle projection, in that there is a natural isomorphism of formal smooth sets of the form

In particular this implies immediately that smooth sections (def. ) of the tangent bundle

are equivalently morphisms of the form

which we had already identified with tangent vector fields (def. ) in example .

Proof

This follows by an analogous argument as in example , using the Hadamard lemma.

While in infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces (def. ) only infinitesimals to any finite order may exist, in formal smooth sets (def. ) we may find infinitesimals to any arbitrary finite order:

Example

Let be a formal smooth sets (def. ) a sub-formal smooth set. Then the infinitesimal neighbourhood to arbitrary infinitesimal order of in is the formal smooth set whose plots are those plots of

such that their reduction (def. )

factors through a plot of .

This allows to grasp the restriction of field histories to the infinitesimal neighbourhood of a submanifold of spacetime, which will be crucial for the discussion of phase spaces below.

Definition

(field histories on infinitesimal neighbourhood of submanifold of spacetime)

Let be a field bundle (def. ) and let be a submanifold of spacetime.

We write for its infinitesimal neighbourhood in (def. ).

Then the set of field histories restricted to , to be denoted

is the set of section of restricted to the infinitesimal neighbourhood (example ).

We close the discussion of infinitesimal differential geometry by explaining how we may recover the concept of smooth manifolds inside the more general formal smooth sets (def./prop. below). The key point is that the presence of infinitesimals in the theory allows an intrinsic definition of local diffeomorphisms/formally étale morphism (def. and example below). It is noteworthy that the only role this concept plays in the development of field theory below is that smooth manifolds admit triangulations by smooth singular simplices (def. ) so that the concept of fiber integration of differential forms is well defined over manifolds.

Definition

(local diffeomorphism of formal smooth sets)

Let be formal smooth sets (def. ). Then a morphism between them is called a local diffeomorphism or formally étale morphism, denoted

if if for each infinitesimally thickened Cartesian space (def. ) we have a natural identification between the -plots of with those -plots of whose reduction (def. ) comes from an -plot of , hence if we have a natural fiber product of sets of plots

i. e.

for all infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces .

Stated more abstractly, this means that the naturality square of the unit of the infinitesimal shape (def. ) is a pullback square

(Khavkine-Schreiber 17, def. 3.1)

Example

(local diffeomorphism between Cartesian spaces from the general definition)

For two ordinary Cartesian spaces (def. ), regarded as formal smooth sets by example then a morphism between them is a local diffeomorphism in the general sense of def. precisely if it is so in the ordinary sense of def. .

(Khavkine-Schreiber 17, prop. 3.2)

Definition/Proposition

A smooth manifold of dimension is

- a diffeological space (def. )

such that

-

there exists an indexed set of morphisms of formal smooth sets (def. ) from Cartesian spaces (def. ) (regarded as formal smooth sets via example , example and example ) into , (regarded as a formal smooth set via example and example ) such that

-

every point is in the image of at least one of the ;

-

every is a local diffeomorphism according to def. ;

-

-

the final topology induced by the set of plots of makes a paracompact Hausdorff space.

(Khavkine-Schreiber 17, example 3.4)

For more on smooth manifolds from the perspective of formal smooth sets see at geometry of physics – manifolds and orbifolds.

fermion fields and supergeometry

Field theories of interest crucially involve fermionic fields (def. below), such as the Dirac field (example below), which are subject to the “Pauli exclusion principle”, a key reason for the stability of matter. Mathematically this principle means that these fields have field bundles whose field fiber is not an ordinary manifold, but an odd-graded supermanifold (more on this in remark and remark below).

This “supergeometry” is an immediate generalization of the infinitesimal geometry above, where now the infinitesimal elements in the algebra of functions may be equipped with a grading: one speaks of superalgebra.

The “super”-terminology for something as down-to-earth as the mathematical principle behind the stability of matter may seem unfortunate. For better or worse, this terminology has become standard since the middle of the 20th century. But the concept that today is called supercommutative superalgebra was in fact first considered by Grassmann 1844 who got it right (“Ausdehnungslehre”) but apparently was too far ahead of his time and remained unappreciated.

Beware that considering supergeometry does not necessarily involve considering “supersymmetry”. Supergeometry is the geometry of fermion fields (def. below), and that all matter fields in the observable universe are fermionic has been experimentally established since the Stern-Gerlach experiment in 1922. Supersymmetry, on the other hand, is a hypothetical extension of spacetime-symmetry within the context of supergeometry. Here we do not discuss supersymmetry; for details see instead at geometry of physics – supersymmetry.

Definition

(supercommutative superalgebra)

A real -graded algebra or superalgebra is an associative algebra over the real numbers together with a direct sum decomposition of its underlying real vector space

such that the product in the algebra respects the multiplication in the cyclic group of order 2 :

This is called a supercommutative superalgebra if for all elements which are of homogeneous degree in that

we have

A homomorphism of superalgebras

is a homomorphism of associative algebras over the real numbers such that the -grading is respected in that

For more details on superalgebra see at geometry of physics – superalgebra.

Example

(basic examples of supercommutative superalgebras)

Basic examples of supercommutative superalgebras (def. ) include the following:

-

Every commutative algebra becomes a supercommutative superalgebra by declaring it to be all in even degree: .

-

For a finite dimensional real vector space, then the Grassmann algebra is a supercommutative superalgebra with and .

More explicitly, if is a Cartesian space with canonical dual coordinates then the Grassmann algebra is the real algebra which is generated from the regarded in odd degree and hence subject to the relation

In particular this implies that all the are infinitesimal (def. ):

-

For and two supercommutative superalgebras, there is their tensor product supercommutative superalgebra . For example for a smooth manifold with ordinary algebra of smooth functions regarded as a supercommutative superalgebra by the first example above, the tensor product with a Grassmann algebra (second example above) is the supercommutative superalgebta

whose elements may uniquely be expanded in the form

where the are smooth functions on which are skew-symmetric in their indices.

The following is the direct super-algebraic analog of the definition of infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces (def. ):

Definition

A superpoint is represented by a super-commutative superalgebra (def. ) which as a -graded vector space (super vector space) is a direct sum

of the 1-dimensional even vector space of multiples of 1, with a finite dimensional super vector space that is a nilpotent ideal in in that for each element there exists a natural number such that

More generally, a super Cartesian space is represented by a super-commutative algebra which is the tensor product of algebras of the algebra of smooth functions on an actual Cartesian space of some dimension , with an algebra of functions of a superpoint (example ).

Specifically, for , there is the superpoint

whose algebra of functions is by definition the Grassmann algebra on generators in odd degree (example ).

We write

for the corresponding super Cartesian spaces whose algebra of functions is as in example .

We say that a smooth function between two super Cartesian spaces

is by definition dually a homomorphism of supercommutative superalgebras (def. ) of the form

Example

(superpoint induced by a finite dimensional vector space)

Let be a finite dimensional real vector space. With denoting its dual vector space write for the Grassmann algebra that it generates. This being a supercommutative algebra, it defines a superpoint (def. ).

We denote this superpoint by

All the differential geometry over Cartesian space that we discussed above generalizes immediately to super Cartesian spaces (def. ) if we stricly adhere to the super sign rule which says that whenever two odd-graded elements swap places, a minus sign is picked up. In particular we have the following generalization of the de Rham complex on Cartesian spaces discussed above.

Definition

(super differential forms on super Cartesian spaces)

For a super Cartesian space (def. ), hence the formal dual of the supercommutative superalgebra of the form

with canonical even-graded coordinate functions and odd-graded coordinate functions .

Then the de Rham complex of super differential forms on is, in super-generalization of def. , the -graded commutative algebra

which is generated over from new generators

whose differential is defined in degree-0 by

and extended from there as a bigraded derivation of bi-degree , in super-generalization of def. .

Accordingly, the operation of contraction with tangent vector fields (def. ) has bi-degree if the tangent vector has super-degree :

| generator | bi-degree |

|---|---|

| (0,even) | |

| (0,odd) | |

| (1,even) | |

| (1,odd) |

| derivation | bi-degree |

|---|---|

| (1,even) | |

| (-1, even) | |

| (-1,odd) |

This means that if is in bidegree , and is in bidegree , then

Hence there are two contributions to the sign picked up when exchanging two super-differential forms in the wedge product:

-

there is a “cohomological sign” which for commuting an -forms past an -form is ;

-

in addition there is a “super-grading” sign which for commuting a -graded coordinate function past a -graded coordinate function (possibly under the de Rham differential) is .

For example:

(e.g. Castellani-D’Auria-Fré 91 (II.2.106) and (II.2.109), Deligne-Freed 99, section 6)

Beware that there is also another sign rule for super differential forms used in the literature. See at signs in supergeometry for further discussion.

It is clear now by direct analogy with the definition of formal smooth sets (def. ) what the corresponding supergeometric generalization is. For definiteness we spell it out yet once more:

Definition

A super smooth set is

-

for each super Cartesian space (def. ) a set

to be called the set of smooth functions or plots from to ;

-

for each smooth function between super Cartesian spaces a choice of function

to be thought of as the precomposition operation

such that

-

-

If is the identity function on , then is the identity function on the set of plots .

-

If are two composable smooth functions between infinitesimally thickened Cartesian spaces, then pullback of plots along them consecutively equals the pullback along the composition:

i.e.

-

-

(gluing)

If is such that

is a differentiably good open cover (def. ) then the function which restricts -plots of to a set of -plots

is a bijection onto the set of those tuples of plots, which are “matching families” in that they agree on intersections:

i.e.

Finally, given and two super formal smooth sets, then a smooth function between them

is

-

for each super Cartesian space a function

such that

-

for each smooth function between super Cartesian spaces we have

i.e.

Basing supergeometry on super formal smooth sets is an instance of the general approach to geometry called functorial geometry or topos theory. For more background on this see at geometry of physics – supergeometry.

In direct generalization of example we have:

Example

(super Cartesian spaces are super smooth sets)

Let be a super Cartesian space (def. ) Then it becomes a super smooth set (def. ) by declaring its plots to the algebra homomorphisms .

Under this identification, morphisms between super Cartesian spaces are in natural bijection with their morphisms regarded as super smooth sets.

Stated more abstractly, this statement is an example of the Yoneda embedding over a subcanonical site.

Similarly, in direct generalization of prop. we have:

Proposition

(plots of a super smooth set really are the smooth functions into the smooth smooth set)

Let be a super smooth set (def. ). For any super Cartesian space (def. ) there is a natural function

from the set of homomorphisms of super smooth sets from (regarded as a super smooth set via example ) to , to the set of plots of over , given by evaluating on the identity plot .

This function is a bijection.

This says that the plots of , which initially bootstrap into being as declaring the would-be smooth functions into , end up being the actual smooth functions into .

Proof

This is the statement of the Yoneda lemma over the site of super Cartesian spaces.

We do not need to consider here supermanifolds more general than the super Cartesian spaces (def. ). But for those readers familiar with the concept we include the following direct analog of the characterization of smooth manifolds according to def./prop. :

Definition/Proposition

A supermanifold of dimension super-dimension is

- a super smooth set (def. )

such that

-

there exists an indexed set of morphisms of super smooth sets (def. ) from super Cartesian spaces (def. ) (regarded as super smooth sets via example into , such that

-

for every plot there is a differentiably good open cover (def. ) restricted to which the plot factors through the ;

-

every is a local diffeomorphism according to def. , now with respect not just to infinitesimally thickened points, but with respect to superpoints;

-

-

the bosonic part of is a smooth manifold according to def./prop. .

Finally we have the evident generalization of the smooth moduli space of differential forms from example to supergeometry

Example

(universal smooth moduli spaces of super differential forms)

For write

for the super smooth set (def. ) whose set of plots on a super Cartesian space (def. ) is the set of super differential forms (def. ) of cohomolgical degree

and whose maps of plots is given by pullback of super differential forms.

The de Rham differential on super differential forms applied plot-wise yields a morpism of super smooth sets

As before in def. we then define for any super smooth set its set of differential -forms to be

and we define the de Rham differential on these to be given by postcomposition with (10).

Definition

(bosonic fields and fermionic fields)

For a spacetime, such as Minkowski spacetime (def. ) if a fiber bundle with total space a super Cartesian space (def. ) (or more generally a supermanifold, def./prop. ) is regarded as a super-field bundle (def. ), then

-

the even-graded sections are called the bosonic field histories;

-

the odd-graded sections are called the fermionic field histories.

In components, if is a trivial bundle with fiber a super Cartesian space (def. ) with even-graded coordinates and odd-graded coordinates , then the are called the bosonic field coordinates, and the are called the fermionic field coordinates.

What is crucial for the discussion of field theory is the following immediate supergeometric analog of the smooth structure on the space of field histories from example :

Example

(supergeometric space of field histories)

Let be a super-field bundle (def. , def. ).

Then the space of sections, hence the space of field histories, is the super formal smooth set (def. )

whose plots for a given Cartesian space and superpoint (def. ) with the Cartesian products and regarded as super smooth sets according to example are defined to be the morphisms of super smooth set (def. )

which make the following diagram commute:

Explicitly, if is a Minkowski spacetime (def. ) and a trivial field bundle with field fiber a super vector space (example , example ) this means dually that a plot of the super smooth set of field histories is a homomorphism of supercommutative superalgebras (def. )

which make the following diagram commute:

We will focus on discussing the supergeometric space of field histories (example ) of the Dirac field (def. below). This we consider below in example ; but first we discuss now some relevant basics of general supergeometry.

Example is really a special case of a general relative mapping space-construction as in example . This immediately generalizes also to the supergeometric context.

Definition

(super-mapping space out of a super Cartesian space)

Let be a super Cartesian space (def. ) and let be a super smooth set (def. ). Then the mapping space

of super smooth functions from to is the super formal smooth set whose -plots are the morphisms of super smooth set from the Cartesian product of super Cartesian space to , hence the -plots of :

In direct generalization of the synthetic tangent bundle construction (example ) to supergeometry we have

Definition

Let be a super smooth set (def. ) and the superpoint (9) then the supergeometry-mapping space

is called the odd tangent bundle of .

Example

(mapping space of superpoints)

Let be a finite dimensional real vector space and consider its corresponding superpoint from exampe . Then the mapping space (def. ) out of the superpoint (def. ) into is the Cartesian product

By def. this says that is the “odd tangent bundle” of .

Proof

Let be any super Cartesian space. Then by definition we have the following sequence of natural bijections of sets of plots

Here in the third line we used that the Grassmann algebra is free on its generators in , meaning that a homomorphism of supercommutative superalgebras out of the Grassmann algebra is uniquely fixed by the underlying degree-preserving linear function on these generators. Since in a Grassmann algebra all the generators are in odd degree, this is equivalently a linear map from to the odd-graded real vector space underlying , which is the direct sum .

Then in the fourth line we used that finite direct sums are Cartesian products, so that linear maps into a direct sum are pairs of linear maps into the direct summands.

That all these bijections are natural means that they are compatible with morphisms and therefore this says that and are the same as seen by super-smooth plots, hence that they are isomorphic as super smooth sets.

With this supergeometry in hand we finally turn to defining the Dirac field species:

Example

(field bundle for Dirac field)

For being Minkowski spacetime (def. ), of dimension , , or , let be the spin representation from prop. , whose underlying real vector space is

With

the corresponding superpoint (example ), then the field bundle for the Dirac field on is

hence the field fiber is the superpoint . This is the corresponding spinor bundle on Minkowski spacetime, with fiber in odd super-degree.

The traditional two-component spinor basis from remark provides fermionic field coordinates (def. ) on the field fiber :

Notice that these are -valued odd functions: For instance if then each in turn has two components, a real part and an imaginary part.

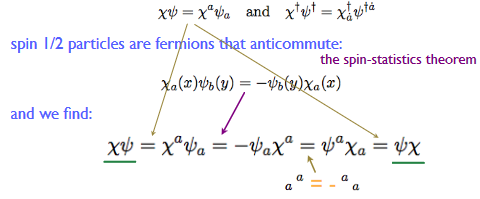

A key point with the field bundle of the Dirac field (example ) is that the field fiber coordinates or are now odd-graded elements in the function algebra on the field fiber, which is the Grassmann algebra . Therefore they anti-commute with each other:

snippet grabbed from (Dermisek 09)

We analyze the special nature of the supergeometry space of field histories of the Dirac field a little (prop. ) below and conclude by highlighting the crucial role of supergeometry (remark below)

Proposition

(space of field histories of the Dirac field)

Let be the super-field bundle (def. ) for the Dirac field over Minkowski spacetime from example .

Then the corresponding supergeometric space of field histories

from example has the following properties:

-

For an ordinary Cartesian space (with no super-geometric thickening, def. ) there is only a single -parameterized collection of field histories, hence a single plot

and this corresponds to the zero section, hence to the trivial Dirac field

-

For a super Cartesian space () with a single super-odd dimension, then -parameterized collections of field histories

are in natural bijection with plots of sections of the bosonic-field bundle with field fiber the spin representation regarded as an ordinary vector space:

Moreover, these two kinds of plots determine the fermionic field space completely: It is in fact isomorphic, as a super vector space, to the bosonic field space shifted to odd degree (as in example ):

Proof

In the first case, the plot is a morphism of super Cartesian spaces (def. ) of the form

By definitions this is dually homomorphism of real supercommutative superalgebras

from the Grassmann algebra on the dual vector space of the spin representation to the ordinary algebras of smooth functions on . But the latter has no elements in odd degree, and hence all the Grassmann generators need to be send to zero.

For the second case, notice that a morphism of the form

is by def. naturally identified with a morphism of the form

where the identification on the right is from example .

By the nature of Cartesian products these morphisms in turn are naturally identified with pairs of morphisms of the form

Now, as in the first point above, here the first component is uniquely fixed to be the zero morphism ; and hence only the second component is free to choose. This is precisely the claim to be shown.

Remark

(supergeometric nature of the Dirac field)

Proposition how two basic facts about the Dirac field, which may superficially seem to be in tension with each other, are properly unified by supergeometry:

-

On the one hand a field history of the Dirac field is not an ordinary section of an ordinary vector bundle. In particular its component functions anti-commute with each other, which is not the case for ordinary functions, and this is crucial for the Lagrangian density of the Dirac field to be well defined, we come to this below in example .

-

On the other hand a field history of the Dirac field is supposed to be a spinor, hence a section of a spinor bundle, which is an ordinary vector bundle.

Therefore prop. serves to shows how, even though a Dirac field is not defined to be an ordinary section of an ordinary vector bundle, it is nevertheless encoded by such an ordinary section: One says that this ordinary section is a “superfield-component” of the Dirac field, the one linear in a Grassmann variable .

This concludes our discussion of the concept of fields itself. In the following chapter we consider the variational calculus of fields.

Last revised on August 2, 2018 at 10:13:52. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.