nLab geometry of physics -- homotopy types

Basic notions of homotopy theory

Traditionally, mathematics and physics have been founded on set theory, whose concept of sets is that of “bags of distinguishable points”.

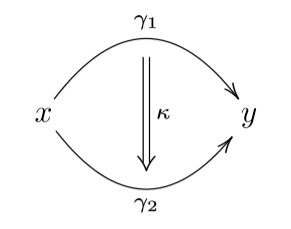

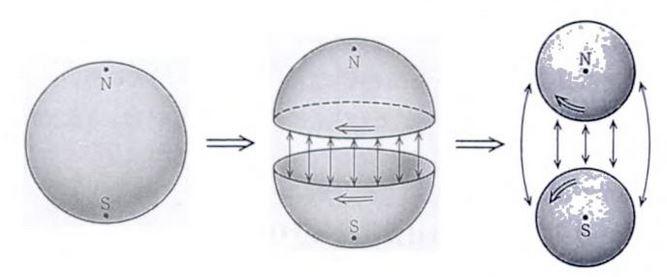

But fundamental physics is governed by the gauge principle. This says that given any two “things”, such as two field histories and , it is in general wrong to ask whether they are equal or not, instead one has to ask where there is a gauge transformation

between them. In mathematics this is called a homotopy.

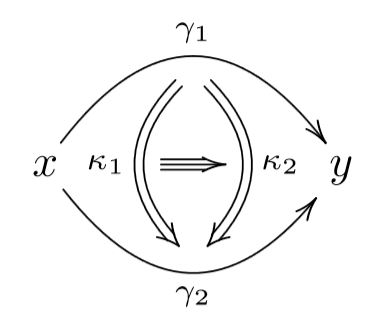

This principle applies also to gauge transformations/homotopies themselves, and thus leads to gauge-of-gauge transformations or homotopies of homotopies

and so on to ever higher gauge transformations or higher homotopies:

This shows that what an here are elements of is not really a set in the sense of set theory. Instead, such a collection of elements with higher gauge transformations/higher homotopies between them is called a homotopy type.

Hence the theory of homotopy types – homotopy theory – is much like set theory, but with the concept of gauge transformation/homotopy built right into its foundations. Homotopy theory is gauged mathematics.

A classical model for homotopy types are simply topological spaces: Their points represent the elements, the continuous paths between points represent the gauge transformations, and continuous deformations of paths represent higher gauge transformations. A central result of homotopy theory is the proof of the homotopy hypothesis, which says that under this identification homotopy types are equivalent to topological spaces viewed, in turn, up to “weak homotopy equivalence”.

In the special case of a homotopy type with a single element , the gauge transformations necessarily go from to itself and hence form a group of symmetries of .

This way homotopy theory subsumes group theory.

If there are higher order gauge-of-gauge transformations/homotopies of homotopies between these symmetry group-elements, then one speaks of 2-groups, 3-groups, … n-groups, and eventually of ∞-groups. When homotopy types are represented by topological spaces, then ∞-groups are represented by topological groups.

This way homotopy theory subsumes parts of topological group theory.

Since, generally, there is more than one element in a homotopy type, these are like “groups with several elements”, and as such they are called groupoids (Def. ).

If there are higher order gauge-of-gauge transformations/homotopies of homotopies between the transformations in such a groupoid, one speaks of 2-groupoids, 3-groupoids, … n-groupoids, and eventually of ∞-groupoids. The plain sets are recovered as the special case of 0-groupoids.

Due to the higher orders appearing here, mathematical structures based not on sets but on homotopy types are also called higher structures.

Hence homotopy types are equivalently ∞-groupoids. This perspective makes explicit that homotopy types are the unification of plain sets with the concept of gauge-symmetry groups.

An efficient way of handling ∞-groupoids is in their explicit guise as Kan complexes (Def. below); these are the non-abelian generalization of the chain complexes used in homological algebra. Indeed, chain homotopy is a special case of the general concept of homotopy, and hence homological algebra forms but a special abelian corner within homotopy theory. Conversely, homotopy theory may be understood as the non-abelian generalization of homological algebra.

Hence, in a self-reflective manner, there are many different but equivalent incarnations of homotopy theory. Below we discuss in turn:

-

∞-groupoids modeled by topological spaces. This is the classical model of homotopy theory familiar from traditional point-set topology, such as covering space-theory.

-

∞-groupoids modeled on simplicial sets, whose fibrant objects are the Kan complexes. This simplicial homotopy theory is Quillen equivalent to topological homotopy theory (the “homotopy hypothesis”), which makes explicit that homotopy theory is not really about topological spaces, but about the ∞-groupoids that these represent.

Ideally, abstract homotopy theory would simply be a complete replacement of set theory, obtained by removing the assumption of strict equality, relaxing it to gauge equivalence/homotopy. As such, abstract homotopy theory would be part and parcel of the foundations of mathematics themselves, not requiring any further discussion. This ideal perspective is the promise of homotopy type theory and may become full practical reality in the next decades.

Until then, abstract homotopy theory has to be formulated on top of the traditional foundations of mathematics provided by set theory, much like one may have to run a Linux emulator on a Windows machine, if one does happen to be stuck with the latter.

A very convenient and powerful such emulator for homotopy theory within set theory is model category theory, originally due to Quillen 67 and highly developed since. This we introduce here.

The idea is to consider ordinary categories (Def. ) but with the understanding that some of their morphisms

should be homotopy equivalences (Def. ), namely similar to isomorphisms (Def. ), but not necessarily satisfying the two equations defining an actual isomorphism

but intended to satisfy this only with equality relaxed to gauge transformation/homotopy:

Such would-be homotopy equivalences are called weak equivalences (Def. below).

In principle, this information already defines a homotopy theory by a construction called simplicial localization, which turns weak equivalences into actual homotopy equivalences in a suitable way.

However, without further tools this construction is unwieldy. The extra structure of a model category (Def. below) on top of a category with weak equivalences provides a set of tools.

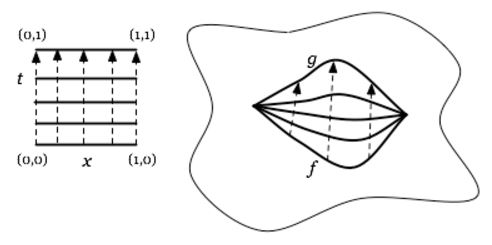

The idea here is to abstract (in Def. below) from the evident concepts in topological homotopy theory of left homotopy (Def. ) and right homotopy (Def. ) between continuous functions: These are provided by continuous functions out of a cylinder space or into a path space , respectively, where in both cases the interval space serves to parameterize the relevant gauge transformation/homotopy.

Now a little reflection shows (this was the seminal insight of Quillen 67) that what really matters in this construction of homotopies is that the path space factors the diagonal morphism from a space to its Cartesian product as

while the cylinder serves to factor the codiagonal morphism as

where in both cases “fibration” means something like well behaved surjection, while “cofibration” means something like satisfying the lifting property (Def. below) against fibrations that are also weak equivalences.

Such factorizations subject to lifting properties is what the definition of model category axiomatizes, in some generality. That this indeed provides a good toolbox for handling homotopy equivalences is shown by the Whitehead theorem in model categories (Lemma below), which exhibits all weak equivalences as actual homotopy equivalences after passage to “good representatives” of objects (fibrant/cofibrant resolutions, Def. below). Accordingly, the first theorem of model category theory (Quillen 67, I.1 theorem 1, reproduced as Theorem below), provides a tractable expression for the hom-sets modulo homotopy equivalence of the underlying category with weak equivalences in terms of actual morphisms out of cofibrant resolutions into fibrant resolutions (Lemma below).

This is then generally how model category-theory serves as a model for homotopy theory: All homotopy-theoretic constructions, such as that of long homotopy fiber sequences (Prop. below), are reflected via constructions of ordinary category theory but applied to suitably resolved objects.

Literature (Dwyer-Spalinski 95)

Definition

A model category is

such that

-

the class makes into a category with weak equivalences, def. ;

-

The pairs and are both weak factorization systems, def. .

One says:

-

elements in are weak equivalences,

-

elements in are cofibrations,

-

elements in are fibrations,

-

elements in are acyclic cofibrations,

-

elements in are acyclic fibrations.

The form of def. is due to (Joyal, def. E.1.2). It implies various other conditions that (Quillen 67) demands explicitly, see prop. and prop. below.

We now dicuss the concept of weak factorization systems (Def. below) appearing in def. .

Factorization systems

Definition

Let be any category. Given a diagram in of the form

then an extension of the morphism along the morphism is a completion to a commuting diagram of the form

Dually, given a diagram of the form

then a lift of through is a completion to a commuting diagram of the form

Combining these cases: given a commuting square

then a lifting in the diagram is a completion to a commuting diagram of the form

Given a sub-class of morphisms , then

- a morphism as above is said to have the right lifting property against or to be a -injective morphism if in all square diagrams with on the right and any on the left a lift exists.

dually:

- a morphism is said to have the left lifting property against or to be a -projective morphism if in all square diagrams with on the left and any on the left a lift exists.

Definition

A weak factorization system (WFS) on a category is a pair of classes of morphisms of such that

-

Every morphism of may be factored as the composition of a morphism in followed by one in

-

The classes are closed under having the lifting property, def. , against each other:

-

is precisely the class of morphisms having the left lifting property against every morphisms in ;

-

is precisely the class of morphisms having the right lifting property against every morphisms in .

-

Definition

For a category, a functorial factorization of the morphisms in is a functor

which is a section of the composition functor .

Remark

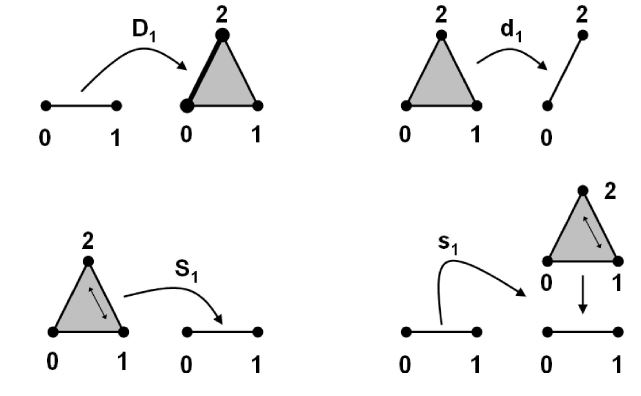

In def. we are using the following standard notation, see at simplex category and at nerve of a category:

Write and for the ordinal numbers, regarded as posets and hence as categories. The arrow category is equivalently the functor category , while has as objects pairs of composable morphisms in . There are three injective functors , where omits the index in its image. By precomposition, this induces functors . Here

-

sends a pair of composable morphisms to their composition;

-

sends a pair of composable morphisms to the first morphisms;

-

sends a pair of composable morphisms to the second morphisms.

Definition

A weak factorization system, def. , is called a functorial weak factorization system if the factorization of morphisms may be chosen to be a functorial factorization , def. , i.e. such that lands in and in .

Remark

Not all weak factorization systems are functorial, def. , although most (including those produced by the small object argument (prop. below), with due care) are.

Proposition

Let be a category and let be a class of morphisms. Write and , respectively, for the sub-classes of -projective morphisms and of -injective morphisms, def. . Then:

-

Both classes contain the class of isomorphism of .

-

Both classes are closed under composition in .

is also closed under transfinite composition.

-

Both classes are closed under forming retracts in the arrow category (see remark ).

-

is closed under forming pushouts of morphisms in (“cobase change”).

is closed under forming pullback of morphisms in (“base change”).

-

is closed under forming coproducts in .

is closed under forming products in .

Proof

We go through each item in turn.

containing isomorphisms

Given a commuting square

with the left morphism an isomorphism, then a lift is given by using the inverse of this isomorphism . Hence in particular there is a lift when and so . The other case is formally dual.

closure under composition

Given a commuting square of the form

consider its pasting decomposition as

Now the bottom commuting square has a lift, by assumption. This yields another pasting decomposition

and now the top commuting square has a lift by assumption. This is now equivalently a lift in the total diagram, showing that has the right lifting property against and is hence in . The case of composing two morphisms in is formally dual. From this the closure of under transfinite composition follows since the latter is given by colimits of sequential composition and successive lifts against the underlying sequence as above constitutes a cocone, whence the extension of the lift to the colimit follows by its universal property.

closure under retracts

Let be the retract of an , i.e. let there be a commuting diagram of the form.

Then for

a commuting square, it is equivalent to its pasting composite with that retract diagram

Here the pasting composite of the two squares on the right has a lift, by assumption:

By composition, this is also a lift in the total outer rectangle, hence in the original square. Hence has the left lifting property against all and hence is in . The other case is formally dual.

closure under pushout and pullback

Let and and let

be a pullback diagram in . We need to show that has the right lifting property with respect to all . So let

be a commuting square. We need to construct a diagonal lift of that square. To that end, first consider the pasting composite with the pullback square from above to obtain the commuting diagram

By the right lifting property of , there is a diagonal lift of the total outer diagram

By the universal property of the pullback this gives rise to the lift in

In order for to qualify as the intended lift of the total diagram, it remains to show that

commutes. To do so we notice that we obtain two cones with tip :

-

one is given by the morphisms

with universal morphism into the pullback being

-

the other by

- .

with universal morphism into the pullback being

- .

The commutativity of the diagrams that we have established so far shows that the first and second morphisms here equal each other, respectively. By the fact that the universal morphism into a pullback diagram is unique this implies the required identity of morphisms.

The other case is formally dual.

closure under (co-)products

Let be a set of elements of . Since colimits in the presheaf category are computed componentwise, their coproduct in this arrow category is the universal morphism out of the coproduct of objects induced via its universal property by the set of morphisms :

Now let

be a commuting square. This is in particular a cocone under the coproduct of objects, hence by the universal property of the coproduct, this is equivalent to a set of commuting diagrams

By assumption, each of these has a lift . The collection of these lifts

is now itself a compatible cocone, and so once more by the universal property of the coproduct, this is equivalent to a lift in the original square

This shows that the coproduct of the has the left lifting property against all and is hence in . The other case is formally dual.

An immediate consequence of prop. is this:

Corollary

Let be a category with all small colimits, and let be a sub-class of its morphisms. Then every -injective morphism, def. , has the right lifting property, def. , against all -relative cell complexes, def. and their retracts, remark .

Remark

By a retract of a morphism in some category we mean a retract of as an object in the arrow category , hence a morphism such that in there is a factorization of the identity on through

This means equivalently that in there is a commuting diagram of the form

Lemma

In every category the class of isomorphisms is preserved under retracts in the sense of remark .

Proof

For

a retract diagram and an isomorphism, the inverse to is given by the composite

More generally:

Proposition

Given a model category in the sense of def. , then its class of weak equivalences is closed under forming retracts (in the arrow category, see remark ).

Proof

Let

be a commuting diagram in the given model category, with a weak equivalence. We need to show that then also .

First consider the case that .

In this case, factor as a cofibration followed by an acyclic fibration. Since and by two-out-of-three (def. ) this is even a factorization through an acyclic cofibration followed by an acyclic fibration. Hence we obtain a commuting diagram of the following form:

where is uniquely defined and where is any lift of the top middle vertical acyclic cofibration against . This now exhibits as a retract of an acyclic fibration. These are closed under retract by prop. .

Now consider the general case. Factor as an acyclic cofibration followed by a fibration and form the pushout in the top left square of the following diagram

where the other three squares are induced by the universal property of the pushout, as is the identification of the middle horizontal composite as the identity on . Since acyclic cofibrations are closed under forming pushouts by prop. , the top middle vertical morphism is now an acyclic fibration, and hence by assumption and by two-out-of-three so is the middle bottom vertical morphism.

Thus the previous case now gives that the bottom left vertical morphism is a weak equivalence, and hence the total left vertical composite is.

Lemma

Consider a composite morphism

-

If has the left lifting property against , then is a retract of .

-

If has the right lifting property against , then is a retract of .

Proof

We discuss the first statement, the second is formally dual.

Write the factorization of as a commuting square of the form

By the assumed lifting property of against there exists a diagonal filler making a commuting diagram of the form

By rearranging this diagram a little, it is equivalent to

Completing this to the right, this yields a diagram exhibiting the required retract according to remark :

Small object argument

Given a set of morphisms in some category , a natural question is how to factor any given morphism through a relative -cell complex, def. , followed by a -injective morphism, def.

A first approximation to such a factorization turns out to be given simply by forming by attaching all possible -cells to . Namely let

be the set of all ways to find a -cell attachment in , and consider the pushout of the coproduct of morphisms in over all these:

This gets already close to producing the intended factorization:

First of all the resulting map is a -relative cell complex, by construction.

Second, by the fact that the coproduct is over all commuting squres to , the morphism itself makes a commuting diagram

and hence the universal property of the colimit means that is indeed factored through that -cell complex ; we may suggestively arrange that factorizing diagram like so:

This shows that, finally, the colimiting co-cone map – the one that now appears diagonally – almost exhibits the desired right lifting of against the . The failure of that to hold on the nose is only the fact that a horizontal map in the middle of the above diagram is missing: the diagonal map obtained above lifts not all commuting diagrams of into , but only those where the top morphism factors through .

The idea of the small object argument now is to fix this only remaining problem by iterating the construction: next factor in the same way into

and so forth. Since relative -cell complexes are closed under composition, at stage the resulting is still a -cell complex, getting bigger and bigger. But accordingly, the failure of the accompanying to be a -injective morphism becomes smaller and smaller, for it now lifts against all diagrams where factors through , which intuitively is less and less of a condition as the grow larger and larger.

The concept of small object is just what makes this intuition precise and finishes the small object argument. For the present purpose we just need the following simple version:

Definition

For a category and a sub-set of its morphisms, say that these have small domains if there is an ordinal (def. ) such that for every and for every -relative cell complex given by a transfinite composition (def. )

every morphism factors through a stage of order :

The above discussion proves the following:

Proposition

(small object argument)

Let be a locally small category with all small colimits. If a set of morphisms has all small domains in the sense of def. , then every morphism in factors through a -relative cell complex, def. , followed by a -injective morphism, def.

Homotopy

We discuss how the concept of homotopy is abstractly realized in model categories, def. .

Definition

Let be a model category, def. , and an object.

- A path space object for is a factorization of the diagonal as

where is a weak equivalence and is a fibration.

- A cylinder object for is a factorization of the codiagonal (or “fold map”) as

where is a weak equivalence. and is a cofibration.

Remark

For every object in a model category, a cylinder object and a path space object according to def. exist: the factorization axioms guarantee that there exists

-

a factorization of the codiagonal as

-

a factorization of the diagonal as

The cylinder and path space objects obtained this way are actually better than required by def. : in addition to being just a weak equivalence, for these this is actually an acyclic fibration, and dually in addition to being a weak equivalence, for these it is actually an acyclic cofibrations.

Some authors call cylinder/path-space objects with this extra property “very good” cylinder/path-space objects, respectively.

One may also consider dropping a condition in def. : what mainly matters is the weak equivalence, hence some authors take cylinder/path-space objects to be defined as in def. but without the condition that is a cofibration and without the condition that is a fibration. Such authors would then refer to the concept in def. as “good” cylinder/path-space objects.

The terminology in def. follows the original (Quillen 67, I.1 def. 4). With the induced concept of left/right homotopy below in def. , this admits a quick derivation of the key facts in the following, as we spell out below.

Lemma

Let be a model category. If is cofibrant, then for every cylinder object of , def. , not only is a cofibration, but each

is an acyclic cofibration separately.

Dually, if is fibrant, then for every path space object of , def. , not only is a cofibration, but each

is an acyclic fibration separately.

Proof

We discuss the case of the path space object. The other case is formally dual.

First, that the component maps are weak equivalences follows generally: by definition they have a right inverse and so this follows by two-out-of-three (def. ).

But if is fibrant, then also the two projection maps out of the product are fibrations, because they are both pullbacks of the fibration

hence is the composite of two fibrations, and hence itself a fibration, by prop. .

Path space objects are very non-unique as objects up to isomorphism:

Example

If is a fibrant object in a model category, def. , and for and two path space objects for , def. , then the fiber product is another path space object for : the pullback square

gives that the induced projection is again a fibration. Moreover, using lemma and two-out-of-three (def. ) gives that is a weak equivalence.

For the case of the canonical topological path space objects of def , with then this new path space object is , the mapping space out of the standard interval of length 2 instead of length 1.

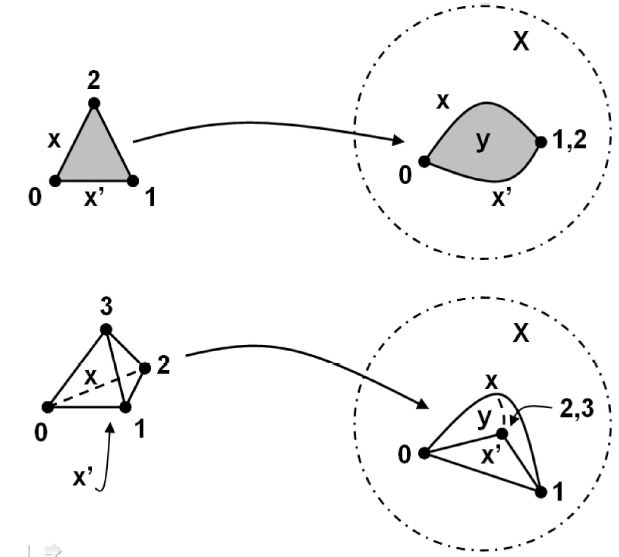

Definition

(abstract left homotopy and abstract right homotopy

Let be two parallel morphisms in a model category.

- A left homotopy is a morphism from a cylinder object of , def. , such that it makes this diagram commute:

- A right homotopy is a morphism to some path space object of , def. , such that this diagram commutes:

Lemma

Let be two parallel morphisms in a model category.

-

Let be cofibrant. If there is a left homotopy then there is also a right homotopy (def. ) with respect to any chosen path space object.

-

Let be fibrant. If there is a right homotopy then there is also a left homotopy with respect to any chosen cylinder object.

In particular if is cofibrant and is fibrant, then by going back and forth it follows that every left homotopy is exhibited by every cylinder object, and every right homotopy is exhibited by every path space object.

Proof

We discuss the first case, the second is formally dual. Let be the given left homotopy. Lemma implies that we have a lift in the following commuting diagram

where on the right we have the chosen path space object. Now the composite is a right homotopy as required:

Proposition

For a cofibrant object in a model category and a fibrant object, then the relations of left homotopy and of right homotopy (def. ) on the hom set coincide and are both equivalence relations.

Proof

That both relations coincide under the (co-)fibrancy assumption follows directly from lemma .

The symmetry and reflexivity of the relation is obvious.

That right homotopy (hence also left homotopy) with domain is a transitive relation follows from using example to compose path space objects.

The homotopy category

We discuss the construction that takes a model category, def. , and then universally forces all its weak equivalences into actual isomorphisms.

Definition

(homotopy category of a model category)

Let be a model category, def. . Write for the category whose

-

objects are those objects of which are both fibrant and cofibrant;

-

morphisms are the homotopy classes of morphisms of , hence the equivalence classes of morphism under the equivalence relation of prop. ;

and whose composition operation is given on representatives by composition in .

This is, up to equivalence of categories, the homotopy category of the model category .

Proposition

Def. is well defined, in that composition of morphisms between fibrant-cofibrant objects in indeed passes to homotopy classes.

Proof

Fix any morphism between fibrant-cofibrant objects. Then for precomposition

to be well defined, we need that with also . But by prop we may take the homotopy to be exhibited by a right homotopy , for which case the statement is evident from this diagram:

For postcomposition we may choose to exhibit homotopy by left homotopy and argue dually.

We now spell out that def. indeed satisfies the universal property that defines the localization of a category with weak equivalences at its weak equivalences.

Lemma

(Whitehead theorem in model categories)

Let be a model category. A weak equivalence between two objects which are both fibrant and cofibrant is a homotopy equivalence (1).

Proof

By the factorization axioms in the model category and by two-out-of-three (def. ), every weak equivalence factors through an object as an acyclic cofibration followed by an acyclic fibration. In particular it follows that with and both fibrant and cofibrant, so is , and hence it is sufficient to prove that acyclic (co-)fibrations between such objects are homotopy equivalences.

So let be an acyclic fibration between fibrant-cofibrant objects, the case of acyclic cofibrations is formally dual. Then in fact it has a genuine right inverse given by a lift in the diagram

To see that is also a left inverse up to left homotopy, let be any cylinder object on (def. ), hence a factorization of the codiagonal on as a cofibration followed by a an acyclic fibration

and consider the commuting square

which commutes due to being a genuine right inverse of . By construction, this commuting square now admits a lift , and that constitutes a left homotopy .

Definition

(fibrant resolution and cofibrant resolution)

Given a model category , consider a choice for each object of

-

a factorization

of the initial morphism (Def. ), such that when is already cofibrant then ;

-

a factorization

of the terminal morphism (Def. ), such that when is already fibrant then .

Write then

for the functor to the homotopy category, def. , which sends an object to the object and sends a morphism to the homotopy class of the result of first lifting in

and then lifting (here: extending) in

Proof

First of all, the object is indeed both fibrant and cofibrant (as well as related by a zig-zag of weak equivalences to ):

Now to see that the image on morphisms is well defined. First observe that any two choices of the first lift in the definition are left homotopic to each other, exhibited by lifting in

Hence also the composites are left homotopic to each other, and since their domain is cofibrant, then by lemma they are also right homotopic by a right homotopy . This implies finally, by lifting in

that also and are right homotopic, hence that indeed represents a well-defined homotopy class.

Finally to see that the assignment is indeed functorial, observe that the commutativity of the lifting diagrams for and imply that also the following diagram commutes

Now from the pasting composite

one sees that is a lift of and hence the same argument as above gives that it is homotopic to the chosen .

For the following, recall the concept of natural isomorphism between functors: for two functors, then a natural transformation is for each object a morphism in , such that for each morphism in the following is a commuting square:

Such is called a natural isomorphism if its are isomorphisms for all objects .

Definition

(localization of a category category with weak equivalences)

For a category with weak equivalences, its localization at the weak equivalences is, if it exists,

such that

-

sends weak equivalences to isomorphisms;

-

is universal with this property, in that:

for any functor out of into any category , such that takes weak equivalences to isomorphisms, it factors through up to a natural isomorphism

and this factorization is unique up to unique isomorphism, in that for and two such factorizations, then there is a unique natural isomorphism making the evident diagram of natural isomorphisms commute.

Theorem

(convenient localization of model categories)

For a model category, the functor in def. (for any choice of and ) exhibits as indeed being the localization of the underlying category with weak equivalences at its weak equivalences, in the sense of def. :

Proof

First, to see that that indeed takes weak equivalences to isomorphisms: By two-out-of-three (def. ) applied to the commuting diagrams shown in the proof of lemma , the morphism is a weak equivalence if is:

With this the “Whitehead theorem for model categories”, lemma , implies that represents an isomorphism in .

Now let be any functor that sends weak equivalences to isomorphisms. We need to show that it factors as

uniquely up to unique natural isomorphism. Now by construction of and in def. , is the identity on the full subcategory of fibrant-cofibrant objects. It follows that if exists at all, it must satisfy for all with and both fibrant and cofibrant that

(hence in particular ).

But by def. that already fixes on all of , up to unique natural isomorphism. Hence it only remains to check that with this definition of there exists any natural isomorphism filling the diagram above.

To that end, apply to the above commuting diagram to obtain

Here now all horizontal morphisms are isomorphisms, by assumption on . It follows that defining makes the required natural isomorphism:

Remark

Due to theorem we may suppress the choices of cofibrant and fibrant replacement in def. and just speak of the localization functor

up to natural isomorphism.

In general, the localization of a category with weak equivalences (def. ) may invert more morphisms than just those in . However, if the category admits the structure of a model category , then its localization precisely only inverts the weak equivalences:

Proposition

(localization of model categories inverts precisely the weak equivalences)

Let be a model category (def. ) and let be its localization functor (def. , theorem ). Then a morphism in is a weak equivalence precisely if is an isomorphism in .

(e.g. Goerss-Jardine 96, II, prop 1.14)

While the construction of the homotopy category in def. combines the restriction to good (fibrant/cofibrant) objects with the passage to homotopy classes of morphisms, it is often useful to consider intermediate stages:

Definition

Given a model category , write

for the system of full subcategory inclusions of:

-

the category of fibrant-cofibrant objects ,

all regarded a categories with weak equivalences (def. ), via the weak equivalences inherited from , which we write , and .

Remark

(categories of fibrant objects and cofibration categories)

Of course the subcategories in def. inherit more structure than just that of categories with weak equivalences from . and each inherit “half” of the factorization axioms. One says that has the structure of a “fibration category” called a “Brown-category of fibrant objects”, while has the structure of a “cofibration category”.

We discuss properties of these categories of (co-)fibrant objects below in Homotopy fiber sequences.

The proof of theorem immediately implies the following:

Corollary

For a model category, the restriction of the localization functor from def. (using remark ) to any of the sub-categories with weak equivalences of def.

exhibits equivalently as the localization also of these subcategories with weak equivalences, at their weak equivalences. In particular there are equivalences of categories

The following says that for computing the hom-sets in the homotopy category, even a mixed variant of the above will do; it is sufficient that the domain is cofibrant and the codomain is fibrant:

Lemma

(hom-sets of homotopy category via mapping cofibrant resolutions into fibrant resolutions)

For with cofibrant and fibrant, and for fibrant/cofibrant replacement functors as in def. , then the morphism

(on homotopy classes of morphisms, well defined by prop. ) is a natural bijection.

Proof

We may factor the morphism in question as the composite

This shows that it is sufficient to see that for cofibrant and fibrant, then

is an isomorphism, and dually that

is an isomorphism. We discuss this for the former; the second is formally dual:

First, that is surjective is the lifting property in

which says that any morphism comes from a morphism under postcomposition with .

Second, that is injective is the lifting property in

which says that if two morphisms become homotopic after postcomposition with , then they were already homotopic before.

We record the following fact which will be used in part 1.1 (here):

Lemma

Let be a model category (def. ). Then every commuting square in its homotopy category (def. ) is, up to isomorphism of squares, in the image of the localization functor of a commuting square in (i.e.: not just commuting up to homotopy).

Proof

Let

be a commuting square in the homotopy category. Writing the same symbols for fibrant-cofibrant objects in and for morphisms in representing these, then this means that in there is a left homotopy of the form

Consider the factorization of the top square here through the mapping cylinder of

This exhibits the composite as an alternative representative of in , and as an alternative representative for , and the commuting square

as an alternative representative of the given commuting square in .

Derived functors

Definition

For and two categories with weak equivalences, def. , then a functor is called a homotopical functor if it sends weak equivalences to weak equivalences.

Definition

Given a homotopical functor (def. ) between categories with weak equivalences whose homotopy categories and exist (def. ), then its (“total”) derived functor is the functor between these homotopy categories which is induced uniquely, up to unique isomorphism, by their universal property (def. ):

Remark

While many functors of interest between model categories are not homotopical in the sense of def. , many become homotopical after restriction to the full subcategories of fibrant objects or of cofibrant objects, def. . By corollary this is just as good for the purpose of homotopy theory.

Therefore one considers the following generalization of def. :

Definition

(left and right derived functors)

Consider a functor out of a model category (def. ) into a category with weak equivalences (def. ).

-

If the restriction of to the full subcategory of fibrant object becomes a homotopical functor (def. ), then the derived functor of that restriction, according to def. , is called the right derived functor of and denoted by :

-

If the restriction of to the full subcategory of cofibrant object becomes a homotopical functor (def. ), then the derived functor of that restriction, according to def. , is called the left derived functor of and denoted by :

The key fact that makes def. practically relevant is the following:

Proposition

Let be a model category with full subcategories of fibrant objects and of cofibrant objects respectively (def. ). Let be a category with weak equivalences.

-

A functor out of the category of fibrant objects

is a homotopical functor, def. , already if it sends acyclic fibrations to weak equivalences.

-

A functor out of the category of cofibrant objects

is a homotopical functor, def. , already if it sends acyclic cofibrations to weak equivalences.

The following proof refers to the factorization lemma, whose full statement and proof we postpone to further below (lemma ).

Proof

We discuss the case of a functor on a category of fibrant objects , def. . The other case is formally dual.

Let be a weak equivalence in . Choose a path space object (def. ) and consider the diagram

where the square is a pullback and on the top left is our notation for the universal cone object. (Below we discuss this in more detail, it is the mapping cocone of , def. ).

Here:

-

is an acyclic fibration because it is the pullback of .

-

is a weak equivalence, because the factorization lemma states that the composite vertical morphism factors through a weak equivalence, hence if is a weak equivalence, then is by two-out-of-three (def. ).

Now apply the functor to this diagram and use the assumption that it sends acyclic fibrations to weak equivalences to obtain

But the factorization lemma , in addition says that the vertical composite is a fibration, hence an acyclic fibration by the above. Therefore also is a weak equivalence. Now the claim that also is a weak equivalence follows with applying two-out-of-three (def. ) twice.

Corollary

Let be model categories and consider a functor. Then:

-

If preserves cofibrant objects and acyclic cofibrations between these, then its left derived functor (def. ) exists, fitting into a diagram

-

If preserves fibrant objects and acyclic fibrants between these, then its right derived functor (def. ) exists, fitting into a diagram

Proposition

(construction of left/right derived functors)

Let be a functor between two model categories (def. ).

-

If preserves fibrant objects and weak equivalences between fibrant objects, then the total right derived functor (def. ) in

is given, up to isomorphism, on any object by appying to a fibrant replacement of and then forming a cofibrant replacement of the result:

-

If preserves cofibrant objects and weak equivalences between cofibrant objects, then the total left derived functor (def. ) in

is given, up to isomorphism, on any object by appying to a cofibrant replacement of and then forming a fibrant replacement of the result:

Proof

We discuss the first case, the second is formally dual. By the proof of theorem we have

But since is a homotopical functor on fibrant objects, the cofibrant replacement morphism is a weak equivalence in , hence becomes an isomorphism under . Therefore

Now since is assumed to preserve fibrant objects, is fibrant in , and hence acts on it (only) by cofibrant replacement.

Quillen adjunctions

In practice it turns out to be useful to arrange for the assumptions in corollary to be satisfied by pairs of adjoint functors (Def. ). Recall that this is a pair of functors and going back and forth between two categories

such that there is a natural bijection between hom-sets with on the left and those with on the right (?):

for all objects and . This being natural (Def. ) means that is a natural transformation, hence that for all morphisms and the following is a commuting square:

We write to indicate such an adjunction and call the left adjoint and the right adjoint of the adjoint pair.

The archetypical example of a pair of adjoint functors is that consisting of forming Cartesian products and forming mapping spaces , as in the category of compactly generated topological spaces of def. .

If is any morphism, then the image is called its adjunct, and conversely. The fact that adjuncts are in bijection is also expressed by the notation

For an object , the adjunct of the identity on is called the adjunction unit .

For an object , the adjunct of the identity on is called the adjunction counit .

Adjunction units and counits turn out to encode the adjuncts of all other morphisms by the formulas

-

.

Definition

Let be model categories. A pair of adjoint functors (Def. ) between them

is called a Quillen adjunction, to be denoted

and , are called left/right Quillen functors, respectively, if the following equivalent conditions are satisfied:

-

preserves cofibrations and preserves fibrations;

-

preserves acyclic cofibrations and preserves acyclic fibrations;

-

preserves cofibrations and acyclic cofibrations;

-

preserves fibrations and acyclic fibrations.

Proof

First observe that

-

(i) A left adjoint between model categories preserves acyclic cofibrations precisely if its right adjoint preserves fibrations.

-

(ii) A left adjoint between model categories preserves cofibrations precisely if its right adjoint preserves acyclic fibrations.

We discuss statement (i), statement (ii) is formally dual. So let be an acyclic cofibration in and a fibration in . Then for every commuting diagram as on the left of the following, its -adjunct is a commuting diagram as on the right here:

If preserves acyclic cofibrations, then the diagram on the right has a lift, and so the -adjunct of that lift is a lift of the left diagram. This shows that has the right lifting property against all acylic cofibrations and hence is a fibration. Conversely, if preserves fibrations, the same argument run from right to left gives that preserves acyclic fibrations.

Now by repeatedly applying (i) and (ii), all four conditions in question are seen to be equivalent.

The following is the analog of adjunction unit and adjunction counit (Def. ):

Definition

Let and be model categories (Def. ), and let

be a Quillen adjunction (Def. ). Then

-

a derived adjunction unit at an object is a composition of the form

where

-

is the ordinary adjunction unit (Def. );

-

is a cofibrant resolution in (Def. );

-

is a fibrant resolution in (Def. );

-

-

a derived adjunction counit at an object is a composition of the form

where

-

is the ordinary adjunction counit (Def. );

-

is a fibrant resolution in (Def. );

-

is a cofibrant resolution in (Def. ).

-

We will see that Quillen adjunctions induce ordinary adjoint pairs of derived functors on homotopy categories (Prop. ). For this we first consider the following technical observation:

Lemma

(right Quillen functors preserve path space objects)

Let be a Quillen adjunction, def. .

-

For a fibrant object and a path space object (def. ), then is a path space object for .

-

For a cofibrant object and a cylinder object (def. ), then is a cylinder object for .

Proof

Consider the second case, the first is formally dual.

First Observe that because is left adjoint and hence preserves colimits, hence in particular coproducts.

Hence

is a cofibration.

Second, with cofibrant then also is a cofibrantion, since is a cofibration (lemma ). Therefore by Ken Brown's lemma (prop. ) preserves the weak equivalence .

Proposition

For a Quillen adjunction, def. , also the corresponding left and right derived functors (Def. , via cor. ) form a pair of adjoint functors

Moreover, the adjunction unit and adjunction counit of this derived adjunction are the images of the derived adjunction unit and derived adjunction counit (Def. ) under the localization functors (Theorem ).

Proof

For the first statement, by def. and lemma it is sufficient to see that for with cofibrant and fibrant, then there is a natural bijection

Since by the adjunction isomorphism for such a natural bijection exists before passing to homotopy classes , it is sufficient to see that this respects homotopy classes. To that end, use from lemma that with a cylinder object for , def. , then is a cylinder object for . This implies that left homotopies

given by

are in bijection to left homotopies

given by

This establishes the adjunction. Now regarding the (co-)units: We show this for the adjunction unit, the case of the adjunction counit is formally dual.

First observe that for , then the defining commuting square for the left derived functor from def.

(using fibrant and fibrant/cofibrant replacement functors , from def. with their universal property from theorem , corollary ) gives that

where the second isomorphism holds because the left Quillen functor sends the acyclic cofibration to a weak equivalence.

The adjunction unit of on is the image of the identity under

By the above and the proof of prop. , that adjunction isomorphism is equivalently that of under the isomorphism

of lemma . Hence the derived adjunction unit (Def. ) is the -adjunct of

which indeed (by the formula for adjuncts, Prop. ) is the derived adjunction unit

This suggests to regard passage to homotopy categories and derived functors as itself being a suitable functor from a category of model categories to the category of categories. Due to the role played by the distinction between left Quillen functors and right Quillen functors, this is usefully formulated as a double functor:

Definition

(double category of model categories)

The (very large) double category of model categories is the double category (Def. ) that has

-

as objects: model categories (Def. );

-

as vertical morphisms: left Quillen functors (Def. );

-

as horizontal morphisms: right Quillen functors (Def. );

-

as 2-morphisms natural transformations between the composites of underlying functors:

and composition is given by ordinary composition of functors, horizontally and vertically, and by whiskering-composition of natural transformations.

There is hence a forgetful double functor (Remark )

to the double category of squares (Example ) in the 2-category of categories (Example ), which forgets the model category-structure and the Quillen functor-property.

The following records the 2-functoriality of sending Quillen adjunctions to adjoint pairs of derived functors (Prop. ):

Proposition

(homotopy double pseudofunctor on the double category of model categories)

There is a double pseudofunctor (Remark )

from the double category of model categories (Def. ) to the double category of squares (Example ) in the 2-category Cat (Example ), which sends

-

a model category to its homotopy category of a model category (Def. );

-

a left Quillen functor (Def. ) to its left derived functor (Def. );

-

a right Quillen functor (Def. ) to its right derived functor (Def. );

-

to the “derived natural transformation”

given by the zig-zag

(3)where the unlabeled morphisms are induced by fibrant resolution and cofibrant resolution , respectively (Def. ).

Lemma

(recognizing derived natural isomorphisms)

For the derived natural transformation in (3) to be invertible in the homotopy category, it is sufficient that for every object which is both fibrant and cofibrant the following composite natural transformation

(of with images of fibrant resolution/cofibrant resolution, Def. ) is invertible in the homotopy category, hence that the composite is a weak equivalence (by Prop. ).

Example

(derived functor of left-right Quillen functor)

Let , be model categories (Def. ), and let

be a functor that is both a left Quillen functor as well as a right Quillen functor (Def. ). This means equivalently that there is a 2-morphism in the double category of model categories (Def. ) of the form

It follows that the left derived functor and right derived functor of (Def. ) are naturally isomorphic:

Proof

To see the natural isomorphism : By Prop. this is implied once the derived natural transformation of (4) is a natural isomorphism. By Prop. this is the case, in the present situation, if the composition of

is a weak equivalence. But this is immediate, since the two factors are weak equivalences, by definition of fibrant/cofibrant resolution (Def. ).

The following is the analog of co-reflective subcategories (Def. ) for model categories:

Definition

Let and be model categories (Def. ), and let

be a Quillen adjunction between them (Def. ). Then this may be called

-

a Quillen reflection if the derived adjunction counit (Def. ) is componentwise a weak equivalence;

-

a Quillen co-reflection if the derived adjunction unit (Def. ) is componentwise a weak equivalence.

The main class of examples of Quillen reflections are left Bousfield localizations, discussed as Prop. below.

Proposition

(characterization of Quillen reflections)

Let

be a Quillen adjunction (Def. ) and write

for the induced adjoint pair of derived functors on the homotopy categories, from Prop. .

Then

-

is a Quillen reflection (Def. ) precisely if is a reflective subcategory-inclusion (Def. );

-

is a Quillen co-reflection] (Def. ) precisely if is a co-reflective subcategory-inclusion (Def. );

Proof

By Prop. the components of the adjunction unit/counit of are precisely the images under localization of the derived adjunction unit/counit of . Moreover, by Prop. the localization functor of a model category inverts precisely the weak equivalences. Hence the adjunction (co-)unit of is an isomorphism if and only if the derived (co-)unit of is a weak equivalence, respectively.

With this the statement reduces to the characterization of (co-)reflections via invertible units/counits, respectively, from Prop. .

The following is the analog of adjoint equivalence of categories (Def. ) for model categories:

Definition

For two model categories (Def. ), a Quillen adjunction (def. )

is called a Quillen equivalence, to be denoted

if the following equivalent conditions hold:

-

The right derived functor of (via prop. , corollary ) is an equivalence of categories

-

The left derived functor of (via prop. , corollary ) is an equivalence of categories

-

For every cofibrant object , the derived adjunction unit (Def. )

is a weak equivalence;

and for every fibrant object , the derived adjunction counit (Def. )

is a weak equivalence.

-

For every cofibrant object and every fibrant object , a morphism is a weak equivalence precisely if its adjunct morphism is:

Proof

That follows from prop. (if in an adjoint pair one is an equivalence, then so is the other).

To see the equivalence , notice (prop.) that a pair of adjoint functors is an equivalence of categories precisely if both the adjunction unit and the adjunction counit are natural isomorphisms. Hence it is sufficient to see that the derived adjunction unit/derived adjunction counit (Def. ) indeed represent the adjunction (co-)unit of in the homotopy category. But this is the statement of Prop. .

To see that :

Consider the weak equivalence . Its -adjunct is

by assumption 4) this is again a weak equivalence, which is the requirement for the derived adjunction unit in 3). Dually for derived adjunction counit.

To see :

Consider any a weak equivalence for cofibrant , firbant . Its adjunct sits in a commuting diagram

where is any lift constructed as in def. .

This exhibits the bottom left morphism as the derived adjunction unit (Def. ), hence a weak equivalence by assumption. But since was a weak equivalence, so is (by two-out-of-three). Thereby also and , are weak equivalences by Ken Brown's lemma and the assumed fibrancy of . Therefore by two-out-of-three (def. ) also the adjunct is a weak equivalence.

Example

(trivial Quillen equivalence)

Let be a model category (Def. ). Then the identity functor on constitutes a Quillen equivalence (Def. ) from to itself:

Proof

From prop. it is clear that in this case the derived functors and both are themselves the identity functor on the homotopy category of a model category, hence in particular are an equivalence of categories.

In certain situations the conditions on a Quillen equivalence simplify. For instance:

Proposition

(recognition of Quillen equivalences)

If in a Quillen adjunction (def. ) the right adjoint “creates weak equivalences” (in that a morphism in is a weak equivalence precisly if is) then is a Quillen equivalence (def. ) precisely already if for all cofibrant objects the plain adjunction unit

is a weak equivalence.

Proof

By prop. , generally, is a Quillen equivalence precisely if

-

for every cofibrant object , the derived adjunction unit (Def. )

is a weak equivalence;

-

for every fibrant object , the derived adjunction counit (Def. )

is a weak equivalence.

Consider the first condition: Since preserves the weak equivalence , then by two-out-of-three (def. ) the composite in the first item is a weak equivalence precisely if is.

Hence it is now sufficient to show that in this case the second condition above is automatic.

Since also reflects weak equivalences, the composite in item two is a weak equivalence precisely if its image

under is.

Moreover, assuming, by the above, that on the cofibrant object is a weak equivalence, then by two-out-of-three this composite is a weak equivalence precisely if the further composite with is

By the formula for adjuncts, this composite is the -adjunct of the original composite, which is just

But is a weak equivalence by definition of cofibrant replacement.

The following is the analog of adjoint triples, adjoint quadruples (Remark ), etc. for model categories:

Definition

Let be model categories (Def. ), where and share the same underlying category , and such that the identity functor on constitutes a Quillen equivalence (Def. ):

Then

-

a Quillen adjoint triple of the form

is diagrams in the double category of model categories (Def. ) of the form

such that is the unit of an adjunction and the counit of an adjunction, thus exhibiting Quillen adjunctions

and such that the derived natural transformation of the bottom right square (3) is invertible (a natural isomorphism);

-

a Quillen adjoint triple of the form

is diagram in the double category of model categories (Def. ) of the form

such that is the unit of an adjunction and the counit of an adjunction, thus exhibiting Quillen adjunctions

and such that the derived natural transformation of the top left square square (here) is invertible (a natural isomorphism).

If a Quillen adjoint triple of the first kind overlaps with one of the second kind

we speak of a Quillen adjoint quadruple, and so forth.

Proposition

(Quillen adjoint triple induces adjoint triple of derived functors on homotopy categories)

Given a Quillen adjoint triple (Def. ), the induced derived functors (Def. ) on the homotopy categories form an ordinary adjoint triple (Remark ):

Proof

This follows immediately from the fact that passing to homotopy categories of model categories is a double pseudofunctor from the double category of model categories to the double category of squares in Cat (Prop. ).

Mapping cones

In the context of homotopy theory, a pullback diagram, such as in the definition of the fiber in example

ought to commute only up to a (left/right) homotopy (def. ) between the outer composite morphisms. Moreover, it should satisfy its universal property up to such homotopies.

Instead of going through the full theory of what this means, we observe that this is plausibly modeled by the following construction, and then we check (below) that this indeed has the relevant abstract homotopy theoretic properties.

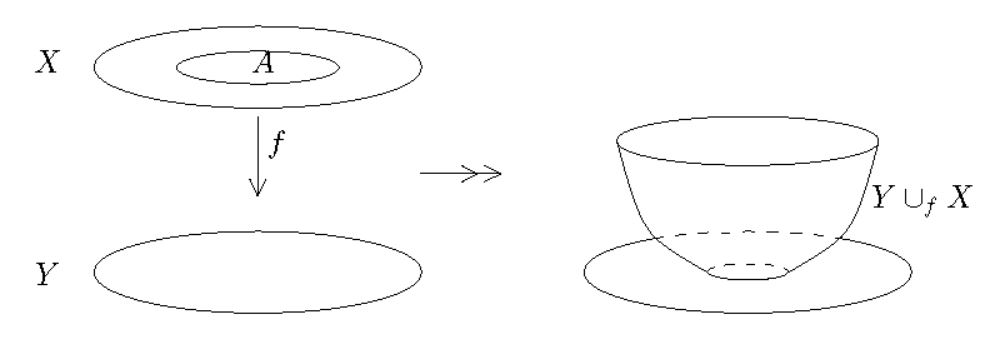

Definition

Let be a model category, def. with its model structure on pointed objects, prop. . For a morphism between cofibrant objects (hence a morphism in , def. ), its reduced mapping cone is the object

in the colimiting diagram

where is a cylinder object for , def. .

Dually, for a morphism between fibrant objects (hence a morphism in , def. ), its mapping cocone is the object

in the following limit diagram

where is a path space object for , def. .

Remark

When we write homotopies (def. ) as double arrows between morphisms, then the limit diagram in def. looks just like the square in the definition of fibers in example , except that it is filled by the right homotopy given by the component map denoted :

Dually, the colimiting diagram for the mapping cone turns to look just like the square for the cofiber, except that it is filled with a left homotopy

Proposition

The colimit appearing in the definition of the reduced mapping cone in def. is equivalent to three consecutive pushouts:

The two intermediate objects appearing here are called

-

the plain reduced cone ;

-

the reduced mapping cylinder .

Dually, the limit appearing in the definition of the mapping cocone in def. is equivalent to three consecutive pullbacks:

The two intermediate objects appearing here are called

-

the based path space object ;

-

the mapping path space or mapping co-cylinder .

Definition

Let be any pointed object.

-

The mapping cone, def. , of is called the reduced suspension of , denoted

Via prop. this is equivalently the coproduct of two copies of the cone on over their base:

This is also equivalently the cofiber, example of , hence (example ) of the wedge sum inclusion:

-

The mapping cocone, def. , of is called the loop space object of , denoted

Via prop. this is equivalently

This is also equivalently the fiber, example of :

Proposition

In pointed topological spaces ,

-

the reduced suspension objects (def. ) induced from the standard reduced cylinder of example are isomorphic to the smash product (def. ) with the 1-sphere, for later purposes we choose to smash on the left and write

Dually:

-

the loop space objects (def. ) induced from the standard pointed path space object are isomorphic to the pointed mapping space (example ) with the 1-sphere

Proof

By immediate inspection: For instance the fiber of is clearly the subspace of the unpointed mapping space on elements that take the endpoints of to the basepoint of .

Example

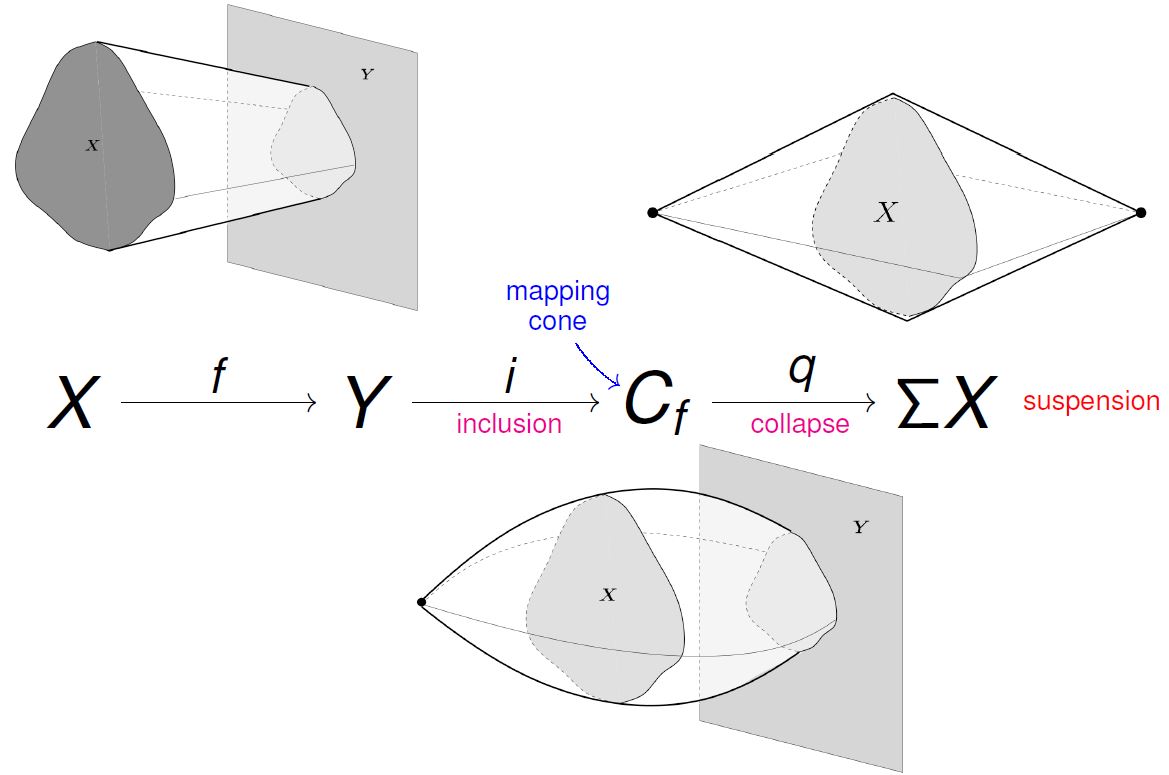

For Top with the standard cyclinder object, def. , then by example , the mapping cone, def. , of a continuous function is obtained by

-

forming the cylinder over ;

-

attaching to one end of that cylinder the space as specified by the map .

-

shrinking the other end of the cylinder to the point.

Accordingly the suspension of a topological space is the result of shrinking both ends of the cylinder on the object two the point. This is homeomoprhic to attaching two copies of the cone on the space at the base of the cone.

(graphics taken from Muro 2010)

Below in example we find the homotopy-theoretic interpretation of this standard topological mapping cone as a model for the homotopy cofiber.

Remark

The formula for the mapping cone in prop. (as opposed to that of the mapping co-cone) does not require the presence of the basepoint: for a morphism in (as opposed to in ) we may still define

where the prime denotes the unreduced cone, formed from a cylinder object in .

Proposition

For a morphism in Top, then its unreduced mapping cone, remark , with respect to the standard cylinder object def. , is isomorphic to the reduced mapping cone, def. , of the morphism (with a basepoint adjoined, def. ) with respect to the standard reduced cylinder (example ):

Proof

By prop. and example , is given by the colimit in over the following diagram:

We may factor the vertical maps to give

This way the top part of the diagram (using the pasting law to compute the colimit in two stages) is manifestly a cocone under the result of applying to the diagram for the unreduced cone. Since is itself given by a colimit, it preserves colimits, and hence gives the partial colimit as shown. The remaining pushout then contracts the remaining copy of the point away.

Example makes it clear that every cycle in that happens to be in the image of can be continuously translated in the cylinder-direction, keeping it constant in , to the other end of the cylinder, where it shrinks away to the point. This means that every homotopy group of , def. , in the image of vanishes in the mapping cone. Hence in the mapping cone the image of under in is removed up to homotopy. This makes it intuitively clear how is a homotopy-version of the cokernel of . We now discuss this formally.

Lemma

Let be a category of cofibrant objects, def. . Then for every morphism the mapping cylinder-construction in def. provides a cofibration resolution of , in that

-

the composite morphism is a cofibration;

-

factors through this morphism by a weak equivalence left inverse to an acyclic cofibration

Dually:

Let be a category of fibrant objects, def. . Then for every morphism the mapping cocylinder-construction in def. provides a fibration resolution of , in that

-

the composite morphism is a fibration;

-

factors through this morphism by a weak equivalence right inverse to an acyclic fibration:

Proof

We discuss the second case. The first case is formally dual.

So consider the mapping cocylinder-construction from prop.

To see that the vertical composite is indeed a fibration, notice that, by the pasting law, the above pullback diagram may be decomposed as a pasting of two pullback diagram as follows

Both squares are pullback squares. Since pullbacks of fibrations are fibrations by prop. , the morphism is a fibration. Similarly, since is fibrant, also the projection map is a fibration (being the pullback of along ).

Since the vertical composite is thereby exhibited as the composite of two fibrations

it is itself a fibration.

Then to see that there is a weak equivalence as claimed:

The universal property of the pullback induces a right inverse of fitting into this diagram

which is a weak equivalence, as indicated, by two-out-of-three (def. ).

This establishes the claim.

Categories of fibrant objects

Below we discuss the homotopy-theoretic properties of the mapping cone- and mapping cocone-constructions from above. Before we do so, we here establish a collection of general facts that hold in categories of fibrant objects and dually in categories of cofibrant objects, def. .

Literature (Brown 73, section 4).

Lemma

Let be a morphism in a category of fibrant objects, def. . Then given any choice of path space objects and , def. , there is a replacement of by a path space object along an acylic fibration, such that has a morphism to which is compatible with the structure maps, in that the following diagram commutes

(Brown 73, section 2, lemma 2)

Proof

Consider the commuting square

Then consider its factorization through the pullback of the right morphism along the bottom morphism,

Finally use the factorization lemma to factor the morphism through a weak equivalence followed by a fibration, the object this factors through serves as the desired path space resolution

Lemma

In a category of fibrant objects , def. , let

be a morphism over some object in and let be any morphism in . Let

be the corresponding morphism pulled back along .

Then

-

if is a fibration then also is a fibration;

-

if is a weak equivalence then also is a weak equivalence.

(Brown 73, section 4, lemma 1)

Proof

For the statement follows from the pasting law which says that if in

the bottom and the total square are pullback squares, then so is the top square. The same reasoning applies for .

Now to see the case that :

Consider the full subcategory of the slice category (def. ) on its fibrant objects, i.e. the full subcategory of the slice category on the fibrations

into . By factorizing for every such fibration the diagonal morphisms into the fiber product through a weak equivalence followed by a fibration, we obtain path space objects relative to :

With these, the factorization lemma (lemma ) applies in .

(Notice that for this we do need the restriction of to the fibrations, because this ensures that the projections are still fibrations, which is used in the proof of the factorization lemma (here).)

So now given any

apply the factorization lemma in to factor it as

By the previous discussion it is sufficient now to show that the base change of to is still a weak equivalence. But by the factorization lemma in , the morphism is right inverse to another acyclic fibration over :

(Notice that if we had applied the factorization lemma of in instead of in then the corresponding triangle on the right here would not commute.)

Now we may reason as before: the base change of the top morphism here is exhibited by the following pasting composite of pullbacks:

The acyclic fibration is preserved by this pullback, as is the identity . Hence the weak equivalence is preserved by two-out-of-three (def. ).

Lemma

In a category of fibrant objects, def. , the pullback of a weak equivalence along a fibration is again a weak equivalence.

(Brown 73, section 4, lemma 2)

Proof

Let be a weak equivalence and be a fibration. We want to show that the left vertical morphism in the pullback

is a weak equivalence.

First of all, using the factorization lemma we may factor as

with the first morphism a weak equivalence that is a right inverse to an acyclic fibration and the right one an acyclic fibration.

Then the pullback diagram in question may be decomposed into two consecutive pullback diagrams

where the morphisms are indicated as fibrations and acyclic fibrations using the stability of these under arbitrary pullback.

This means that the proof reduces to proving that weak equivalences that are right inverse to some acyclic fibration map to a weak equivalence under pullback along a fibration.

Given such with right inverse , consider the pullback diagram

Notice that the indicated universal morphism into the pullback is a weak equivalence by two-out-of-three (def. ).

The previous lemma says that weak equivalences between fibrations over are themselves preserved by base extension along . In total this yields the following diagram

so that with a weak equivalence also is a weak equivalence, as indicated.

Notice that is the morphism that we want to show is a weak equivalence. By two-out-of-three (def. ) for that it is now sufficient to show that is a weak equivalence.

That finally follows now since, by assumption, the total bottom horizontal morphism is the identity. Hence so is the top horizontal morphism. Therefore is right inverse to a weak equivalence, hence is a weak equivalence.

Lemma

Let be a category of fibrant objects, def. in a model structure on pointed objects (prop. ). Given any commuting diagram in of the form

(meaning: both squares commute and equalizes with ) then the localization functor (def. , cor ) takes the morphisms induced by and on fibers (example ) to the same morphism, in the homotopy category.

(Brown 73, section 4, lemma 4)

Proof

First consider the pullback of along : this forms the same kind of diagram but with the bottom morphism an identity. Hence it is sufficient to consider this special case.

Consider the full subcategory of the slice category (def. ) on its fibrant objects, i.e. the full subcategory of the slice category on the fibrations

into . By factorizing for every such fibration the diagonal morphisms into the fiber product through a weak equivalence followed by a fibration, we obtain path space objects relative to :

With these, the factorization lemma (lemma ) applies in .

Let then be a path space object for in the slice over and consider the following commuting square

By factoring this through the pullback and then applying the factorization lemma and then two-out-of-three (def. ) to the factoring morphisms, this may be replaced by a commuting square of the same form, where however the left morphism is an acyclic fibration

This makes also the morphism be a fibration, so that the whole diagram may now be regarded as a diagram in the category of fibrant objects of the slice category over .

As such, the top horizontal morphism now exhibits a right homotopy which under localization (def. ) of the slice model structure (prop. ) we have

The result then follows by observing that we have a commuting square of functors

because, by lemma , the top and right composite sends weak equivalences to isomorphisms, and hence the bottom filler exists by theorem . This implies the claim.

Homotopy fibers

We now discuss the homotopy-theoretic properties of the mapping cone- and mapping cocone-constructions from above.

Literature (Brown 73, section 4).

Remark

The factorization lemma with prop. says that the mapping cocone of a morphism , def. , is equivalently the plain fiber, example , of a fibrant resolution of :

The following prop. says that, up to equivalence, this situation is independent of the specific fibration resolution provided by the factorization lemma (hence by the prescription for the mapping cocone), but only depends on it being some fibration resolution.

Proposition

In the category of fibrant objects , def. , of a model structure on pointed objects (prop. ) consider a morphism of fiber-diagrams, hence a commuting diagram of the form

If and weak equivalences, then so is .

Proof

Factor the diagram in question through the pullback of along

and observe that

-

;

-

is a weak equivalence by assumption and by two-out-of-three (def. );

Moreover, this diagram exhibits as the base change, along , of . Therefore the claim now follows with lemma .

Hence we say:

Definition

Let be a model category and its model category of pointed objects, prop. . For any morphism in its category of fibrant objects , def. , then its homotopy fiber

is the morphism in the homotopy category , def. , which is represented by the fiber, example , of any fibration resolution of (hence any fibration such that factors through a weak equivalence followed by ).

Dually:

For any morphism in its category of cofibrant objects , def. , then its homotopy cofiber

is the morphism in the homotopy category , def. , which is represented by the cofiber, example , of any cofibration resolution of (hence any cofibration such that factors as followed by a weak equivalence).

Proposition

The homotopy fiber in def. is indeed well defined, in that for and two fibration replacements of any morphisms in , then their fibers are isomorphic in .

Proof

It is sufficient to exhibit an isomorphism in from the fiber of the fibration replacement given by the factorization lemma (for any choice of path space object) to the fiber of any other fibration resolution.

Hence given a morphism and a factorization

consider, for any choice of path space object (def. ), the diagram

as in the proof of lemma . Now by repeatedly using prop. :

-

the bottom square gives a weak equivalence from the fiber of to the fiber of ;

-

The square

gives a weak equivalence from the fiber of to the fiber of .

-

Similarly the total vertical composite gives a weak equivalence via

from the fiber of to the fiber of .

Together this is a zig-zag of weak equivalences of the form

between the fiber of and the fiber of . This gives an isomorphism in the homotopy category.

Example

(fibers of Serre fibrations)

In showing that Serre fibrations are abstract fibrations in the sense of model category theory, theorem implies that the fiber (example ) of a Serre fibration, def.

over any point is actually a homotopy fiber in the sense of def. . With prop. this implies that the weak homotopy type of the fiber only depends on the Serre fibration up to weak homotopy equivalence in that if is another Serre fibration fitting into a commuting diagram of the form

then .

In particular this gives that the weak homotopy type of the fiber of a Serre fibration does not change as the basepoint is moved in the same connected component. For let be a path between two points

Then since all objects in are fibrant, and since the endpoint inclusions are weak equivalences, lemma gives the zig-zag of top horizontal weak equivalences in the following diagram:

and hence an isomorphism in the classical homotopy category (def. ).

The same kind of argument applied to maps from the square gives that if are two homotopic paths with coinciding endpoints, then the isomorphisms between fibers over endpoints which they induce are equal. (But in general the isomorphism between the fibers does depend on the choice of homotopy class of paths connecting the basepoints!)

The same kind of argument also shows that if has the structure of a cell complex (def. ) then the restriction of the Serre fibration to one cell may be identified in the homotopy category with , and may be canonically identified so if the fundamental group of is trivial. This is used when deriving the Serre-Atiyah-Hirzebruch spectral sequence for (prop.).

Example

For every continuous function between CW-complexes, def. , then the standard topological mapping cone is the attaching space (example )

of with the standard cone given by collapsing one end of the standard topological cyclinder (def. ) as shown in example .

Equipped with the canonical continuous function

this represents the homotopy cofiber, def. , of with respect to the classical model structure on topological spaces from theorem .

Proof

By prop. , for a CW-complex then the standard topological cylinder object is indeed a cyclinder object in . Therefore by prop. and the factorization lemma , the mapping cone construction indeed produces first a cofibrant replacement of and then the ordinary cofiber of that, hence a model for the homotopy cofiber.

Example

The homotopy fiber of the inclusion of classifying spaces is the n-sphere . See this prop. at Classifying spaces and G-structure.

Example

Suppose a morphism already happens to be a fibration between fibrant objects. The factorization lemma replaces it by a fibration out of the mapping cocylinder , but such that the comparison morphism is a weak equivalence:

Hence by prop. in this case the ordinary fiber of is weakly equivalent to the mapping cocone, def. .

We may now state the abstract version of the statement of prop. :

Proposition

Let be a model category. For any morphism of pointed objects, and for a pointed object, def. , then the sequence

is exact as a sequence of pointed sets.

(Where the sequence here is the image of the homotopy fiber sequence of def. under the hom-functor from example .)

Proof

Let , and denote fibrant-cofibrant objects in representing the given objects of the same name in . Moreover, let be a fibration in representing the given morphism of the same name in .

Then by def. and prop. there is a representative of the homotopy fiber which fits into a pullback diagram of the form

With this the hom-sets in question are represented by genuine morphisms in , modulo homotopy. From this it follows immediately that includes into . Hence it remains to show the converse: that every element in indeed comes from .