nLab McKay correspondence

Context

Representation theory

geometric representation theory

Ingredients

Definitions

representation, 2-representation, ∞-representation

Geometric representation theory

-

Grothendieck group, lambda-ring, symmetric function, formal group

-

principal bundle, torsor, vector bundle, Atiyah Lie algebroid

-

Eilenberg-Moore category, algebra over an operad, actegory, crossed module

Theorems

Cohomology

Special and general types

-

group cohomology, nonabelian group cohomology, Lie group cohomology

-

-

cohomology with constant coefficients / with a local system of coefficients

Special notions

Variants

-

differential cohomology

Extra structure

Operations

Theorems

Contents

Idea

Generally, the McKay correspondence is a subtle correspondence between the theory of finite subgroups of SU(2), the corresponding orbifold singularities (du Val singularities) and that of simple Lie groups falling into the ADE classification.

ADE classification and McKay correspondence

The correspondence may be understood at different levels:

-

McKay quivers. The original correspondence due to McKay 80 is the observation that the McKay quiver associated to the orbifold singularity of a finite subgroup of SU(2) happens to be an extended Dynkin quiver, hence happens to be an extended Dynkin diagram of the kind that also arises in the ADE-classification of simple Lie groups.

More on this in McKay quivers, below.

-

Equivariant K-theory. A more conceptual explanation for this correspondence comes from the classical fact that the blow up of the ADE singularity is given by a sequence of spheres that touch along the vertices of the corresponding Dynkin quiver. In Gonzalez-Sprinberg & Verdier 83 it was shown that the -equivariant K-theory of the singularity is isomorphic to the K-theory of the desingularization such that under this isomorphism the generators of , hence of the representation ring, hence the irreducible representations, map to K-theory classes supported on the exceptional divisors of this blowup. This gives a conceptual geometric/cohomological explanation for the identifications observed by McKay 80.

More on this in As an equivalence of K-theories

-

Seiberg-Witten theory. Under the interpretation of K-theory-classes as D-brane charges, the K-theoretic McKay correspondence of Gonzalez-Sprinberg & Verdier 83 identifies wrapped brane charges of the desingularized space with fractional brane charges at the singularity.

This leads to a further (currently non-rigorous) explanation of the McKay correspondence in terms of the dual worldvolume quantum field theories on these branes, which are N=2 quiver gauge theories: The moduli space of scalar fields of these theories has two “branches”, called the Higgs branch and the Coulomb branch, and the idea is that depending on which of the branches the vacuum state of the theory is in, it describes the brane as being either on the ADE singularity or on its resolution, but since it’s the same quantum field theory in both cases, these two situations are actually suitably equivalent.

More on this in Via N=2 SYM theory below.

Via McKay quivers

Generally, for a finite group and a linear representation of on a finite dimensional complex vector space, the McKay quiver or McKay graph associated with is the quiver whose vertices correspond to the irreducible representations of and which has edges between the th and the th vertex, for the coefficients in the expansion into irreps of the tensor product of representations of with these irreps:

Specifically this applies to the special case where SU(2) a finite subgroup of SU(2) and its defining representation on .

The original McKay correspondence (McKay 80) states that in this case the corresponding McKay quivers are Dynkin quivers/Dynkin diagrams in the same ADE classification as the ADE singularity .

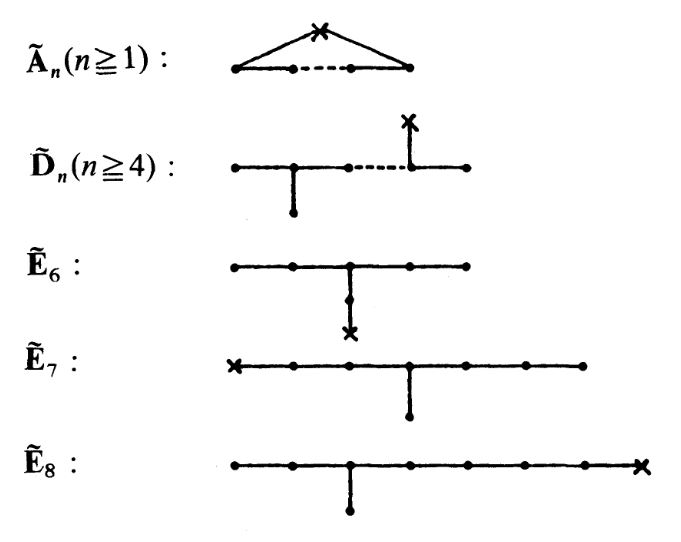

More precisely: If one uses all irreducible representations including the 1-dimensiona trivial representation then one gets the “extended Dynkin diagram”, where the extra node corresponds to . This is the vertex indicated by a cross in the following diagrams:

graphics grabbed from GSV 83, p. 4

In particular, for a cyclic group of order , there are complex irreps and the McKay quiver, i.e. the extended Dynkin diagram, has -vertices, connected by edges to form a circle.

As an equivalence of K-theories

A strong version of the McKay correspondence is obtained when the cohomology theory is taken be (equivariant) K-theory (Gonzalez-Sprinberg & Verdier 83):

Here the McKay correspondence becomes an isomorphism between the equivariant K-theory of an ADE-singularity (equivalently the representation ring ) and the plain K-theory of its blow-up resolution . Much like in topological T-duality, this isomorphism is given by integral transform (Fourier-Mukai transform) through the canonical correspondence that these spaces constitute:

In terms of physics (string theory), the K-theory classes appearing here may be interpreted as groups of fractional D-brane charges (see there). In terms of the worldvolume Chan-Paton-Yang-Mills theory on the D-branes the McKay correspondence is then seen as passage from the Higgs branch to the Coulomb branch (see there).

The proof of these statements generally proceeds by relating both sides of the equivalence to Dynkin diagrams of ADE-type.

The classical McKay correspondence, named after John McKay, is a one-to-one correspondence between the McKay graphs of finite subgroups and the extended Dynkin diagrams of ADE type.

Via super Yang-Mills theory

Various seemingly unrelated structures in mathematics fall into an ADE classification. Notably finite subgroups of SU(2) and compact simple Lie groups do. The way this works usually is that one tries to classify these structures somehow, and ends up finding that the classification is governed by the combinatorics of Dynkin diagrams.

While that does explain a bit, it seems the statement that both the icosahedral group and the Lie group E8 are related to the same Dynkin diagram somehow is still more a question than an answer. Why is that so?

The first key insight is due to Kronheimer 89. He showed that the (resolutions of) the orbifold quotients for finite subgroups of are precisely the generic form of the gauge orbits of the direct product group of s acting in the evident way on the direct sum of -s, where and range over the vertices of the Dynkin diagram, and over its edges.

This becomes more illuminating when interpreted in terms of gauge theory: in a quiver gauge theory the gauge group is a direct product group of factors associated with vertices of a quiver, and the particles which are charged under this gauge group arrange, as a linear representation, into a direct sum of -s, for each edge of the quiver.

Pick one such particle, and follow it around as the gauge group transforms it. The space swept out is its gauge orbit, and Kronheimer 89 says that if the quiver is a Dynkin diagram, then this gauge orbit looks like .

On the other extreme, gauge theories are of interest whose gauge group is not a big direct product, but is a simple Lie group, such as SU(N) or E8. The mechanism that relates the two classes of examples is spontaneous symmetry breaking (“Higgsing”): the ground state energy of the field theory may happen to be achieved by putting the fields at any one point in a higher dimensional space of field configurations, acted on by the gauge group, and fixing any one such point “spontaneously” singles out the corresponding stabilizer subgroup.

Now here is the final ingredient: N=2 D=4 super Yang-Mills theory (“Seiberg-Witten theory”). These theories have a potential such that its vacua break a simple gauge group, such as , down to a Dynkin diagram quiver gauge theory. One place where this is reviewed, physics style, is in Albertsson 03, section 2.3.4.

More precisely, these theories have two different kinds of vacua, those on the “Coulomb branch” and those on the “Higgs branch” depending on whether the scalars of the “vector multiplets” (the gauge field sector) or of the “hypermultiplet” (the matter field sector) vanish. The statement above is for the Higgs branch, but the Coulomb branch is supposed to behave “dually”.

So that then finally is the relation, in the ADE classification, between the simple Lie groups and the finite subgroups of SU(2): start with an N=2 super Yang Mills theory with gauge group a simple Lie group. Let it spontaneously find its vacuum and consider the orbit space of the remaining spontaneously broken symmetry group. That is (a resolution of) the orbifold quotient of by a discrete subgroup of .

Related concepts

References

The original article is

- John McKay, Graphs, singularities, and finite groups Proc. Symp. Pure Math. Vol. 37. No. 183. 1980

As an isomorphism between the equivariant K-theory of ADE-singularity and the plain topological K-theory of its resolution, the McKay correspondence is proven in:

- Gérard Gonzalez-Sprinberg, Jean-Louis Verdier, Construction géométrique de la correspondance de McKay, Ann. Sci. ́École Norm. Sup. 16 3 (1983) 409–449 (numdam:ASENS_1983_4_16_3_409_0)

An analogous discussion for derived categories of coherent sheaves is in

- Tom Bridgeland, Alastair King, Miles Reid, The McKay correspondence as an equivalence of derived categories, J. Amer. Math. Soc. 14 (2001) 535–554 (pdf doi)

See also:

-

Duiliu-Emanuel Diaconescu, Mauro Porta, Francesco Sala, McKay correspondence, cohomological Hall algebras and categorification, Represent. Theory 27 (2023) 933-972 [arXiv:2004.13685, doi:10.1090/ert/649]

-

J. Denef, F. Loeser, Motivic integration, quotient singularities and the McKay correspondence, Compositio Math. 131 (2002) 267–290

-

V. Batyrev, D. Dais, Strong McKay correspondence, string- theoretic Hodge numbers and mirror symmetry, Topology 35 (1996) 901–929 alg-geom/9410001

Introductions and surveys include

-

Graham Leuschke, The McKay correspondence (pdf)

-

Bockland, Character tables and McKay quivers (pdf)

-

Drew Armstrong, Lectures on the McKay correspondence, 2015 (pdf scan of notes)

-

Max Lindh, An Introduction to the McKay Correspondence Master Thesis in Physics (pdf)

-

John Baez, The Geometric McKay Correspondence, (Part I, Part II)

Literature collection:

Last revised on December 1, 2023 at 08:28:55. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.