nLab string theory FAQ

Context

String theory

Ingredients

Critical string models

Extended objects

Topological strings

Backgrounds

Phenomenology

Physics

physics, mathematical physics, philosophy of physics

Surveys, textbooks and lecture notes

theory (physics), model (physics)

experiment, measurement, computable physics

-

-

-

Axiomatizations

-

Tools

-

Structural phenomena

-

Types of quantum field thories

-

Gravity

Formalism

Definition

Spacetime configurations

Properties

Spacetimes

| black hole spacetimes | vanishing angular momentum | positive angular momentum |

|---|---|---|

| vanishing charge | Schwarzschild spacetime | Kerr spacetime |

| positive charge | Reissner-Nordstrom spacetime | Kerr-Newman spacetime |

Quantum theory

Quantum field theory

This page is to provide a non-technical or maybe semi-technical discussion of the nature and role of the theory of fundamental physics known as string theory. For more technical details and further pointers see at string theory.

Contents

- FAQ

- What is string theory?

- What are the equations of string theory?

- Why is string theory controversial?

- Does string theory make predictions? How?

- Is string theory testable?

- Is string theory causal, given that it is not local on the string scale?

- Does string theory predict supersymmetry?

- What is a string vacuum?

- How/why does string theory depend on “backgrounds”?

- Did string theory provide any insight relevant in experimental particle physics?

- Does string theory tell us anything about cosmology, such as the Big bang or cosmic inflation?

- What is the relationship between string theory and quantum field theory?

- Isn’t it fatal that the string perturbation series does not converge?

- How do strings model massive particles?

- How is string theory related to the theory of gravity?

- Do the extra dimensions lead to instability of 4 dimensional spacetime?

- What does it mean to say that string theory has a “landscape of solutions”?

- Is string theory mathematically rigorous?

- What does it mean to say that string theory depends on ‘miracles’, such as anomaly cancellation and avoidance of divergences?

- How does string theory involve homotopy theory, higher geometry and higher category theory?

- References

FAQ

What is string theory?

What is called perturbative string theory is a variant of perturbation theory in quantum field theory (QFT). It is a definition of an “S-matrix” of all scattering amplitudes of quantum objects which is similar to the Feynman perturbation series obtained in perturbative quantum field theory, but crucially different.

One way that the S-matrix in quantum field theory is defined in perturbative field theory is – in worldline formalism – as a formal power series summing over labelled graphs (called Feynman diagrams) of the correlators/n-point functions of a 1-dimensional QFT defined on these graphs (the worldline theory of the particles/virtual particles whose scattering amplitude are to be computed). As a (natural) variant of this, the string perturbation series is defined to be a similar series, but instead of over 1-dimensional graphs now over 2-dimensional surfaces (“worldsheets”) and instead of summing correlators of a 1d QFT, summing correlators of a 2-dimensional QFT, specifically a 2d CFT.

The premise of perturbative string theory as a theory about the observable world is that fundamental scattering processes such as observed in particle accelerator experiments and which are to good approximation described by the Feynman perturbation series (the S-matrix) of the standard model of particle physics are more accurately described by such a string perturbation series.

More conceptually, the premise is that

-

the standard model of particle physics and gravity is just an effective field theory (this is generally expected, independently of string theory)

-

that a string perturbation series can provide its UV-completion – the string scattering amplitudes/S-matrix are finite at each loop, hence are already renormalizations of the underlying effective field theory amplitudes (the higher massive string oscillations serve as natural counterterms to the massless interactions of the effective low energy theory).

While the string perturbation series is a well-defined expression analogous to the Feynman perturbation series, by itself, it lacks a conceptual property of the latter: the Feynman perturbation series is known, in principle, to be the approximation to something, namely to the corresponding complete hence non-perturbative quantum field theory. The idea is that the string perturbation series is similarly the approximation to something, to something which would then be called non-perturbative string theory, but that something has not been identified.

This situation is analogous to the following simple setup: the theory of smooth functions on the real line can be approximated by the theory of Taylor series. Now the notion of the Taylor series has some variants, say to the theory of species. But then the question arises: what is to species as smooth functions were to Taylor series?

There are a host of educated guesses of what non-perturbative string theory might be if anything, but it remains unknown. At some point, the term M-theory had been established for whatever that non-perturbative theory is, but even though it already has a name, it still remains unknown. (Or rather: its full incarnation remains unknown. What is well defined is 11-dimensional supergravity with some M-brane effects and gauge enhancement included, and that is what is presently being studied under the name “M-theory”, see for instance at M-theory on G₂-manifolds; and see also at F-theory.)

Therefore if the qualification “perturbative”/“non-perturbative” is suppressed, then the term “string theory” is quite ambiguous and has frequently led to misunderstanding. Perturbative string theory is a well-defined and formally suggestive variant of established perturbation theory in QFT. Non-perturbative string theory on the other hand is a hypothetical refinement of this perturbative theory of which there are maybe some hints, but which by and large remains mysterious, if it exists at all.

Then why not consider perturbative -brane scattering for any ?

The above motivation of perturbative string theory as the evident result of replacing the definition of an S-matrix perturbation theory, via 1-dimensional Feynman diagrams encoding worldlines of particles, by 2-dimensional diagrams (Riemann surfaces) encoding worldsheets of strings raises the evident question: why stop at strings? Why not consider an S-matrix built as the sum of the correlators of a worldvolume field theory for each -dimensional manifold, encoding the propagation of a membrane for , and generally of (what is called) a p-brane?

To answer this, it is again crucial to distinguish between the perturbation theory and the non-perturbative theory. On the one hand, the study of the string perturbation theory shows that indeed strings interact with and give rise to -branes for many different values of . But the dynamics of all these higher dimensional branes itself seem to be intrinsically non-perturbative. What does not seem to exist is a sensible perturbation series for -brane scattering with .

The reason is that it is hard and seems impossible to make sense of this. There are two technical problems:

-

for then the standard worldvolume action functionals (Nambu-Goto action), are not renormalizable;

-

for the moduli spaces of p+1-manifolds are not controllable.

So for one a) does not know how to define the “Feynman amplitudes” and b) even if one did, one does not know how against what to integrate them.

Each of these two problems in itself makes a -brane perturbation theory for be hard to come by.

That is, incidentally, the very reason for the term “M-theory”. First, there had been the observation that the super 1-brane in 10d target spacetimes is accompanied by a 2-brane in 11d target spacetime, now called the M2-brane (for the history see Mike Duff, The World in Eleven Dimensions). This suggested the evident idea that there ought to be perturbation theory for 2-branes – called membranes, hence that there ought to be “membrane theory” in direct analogy with “string theory”. But the above two problems make a direct such analogy unlikely. Nevertheless, since there might be a less obvious, more sophisticated kind of analogy, Edward Witten proposed to say “M-theory” as an abbreviation, not to commit himself to what exactly might be really going on, and leaving open for the future if “M” is for “membrane” or for something else:

As it has been proposed that the eleven-dimensional theory is a supermembrane theory but there are some reasons to doubt that interpretation, we will non-committally call it the M-theory, leaving to the future the relation of M to membranes. (Hořava-Witten 95)

M stands for magic, mystery, or membrane, according to taste (Witten 95)

What are the equations of string theory?

All local field theories in physics are prominently embodied by key equations, their equations of motion. For instance classical gravity (general relativity) is essentially the theory of Einstein's equations, quantum mechanics is governed by the Schrödinger equation, and so forth.

But perturbative string theory is not a local field theory. Instead it is an S-matrix theory (see What is string theory?). Therefore instead of being given by an equation that picks out the physical trajectories, it is given by a formula for how to compute scattering amplitudes. That formula is the string perturbation series: it says that the probability amplitude for asymptotic states of strings coming in (into a particle collider experiment, say), scattering, and other asymptotic string states emerging (and hitting a detector, say) is a sum over all Riemann surfaces with -punctures of the n-point functions of the given 2d CFT that defines the string vacuum (see at What is a string vacuum?).

More in detail, a string background is equivalently a choice of 2d SCFT of central charge 15 (a “2-spectral triple”), and in terms of this the formula for the S-matrix element/scattering amplitude for a bunch of asymptotic string states coming in, and a bunch of states coming out is schematically of the form

expressing the S-matrix element (scattering amplitude) shown on the left as a formal power series in the string coupling constant with coefficients the integrals over moduli space of super Riemann surfaces of the worldsheet correlators (-point functions) for the given incoming and outgoing string states.

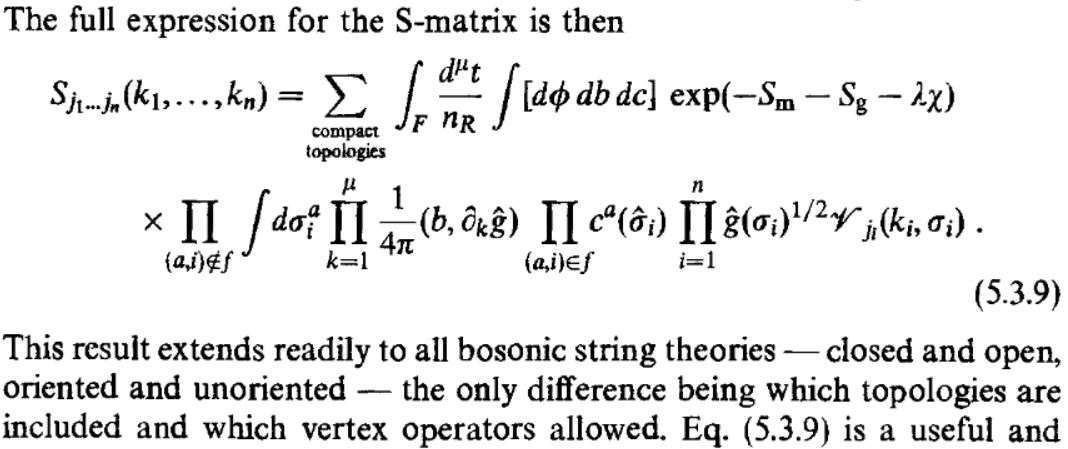

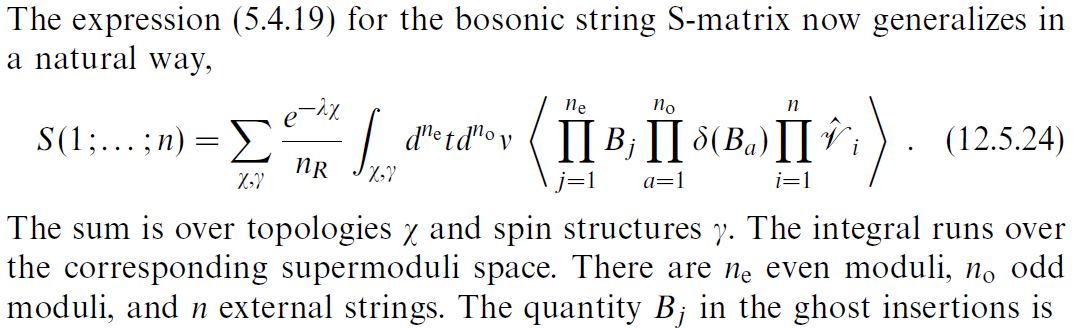

With more technical details filled in, this formula reads as follows: for the bosonic string, as found in Polchinski 01, volume 1, equation (5.3.9)

and for the superstring, as found in Polchinski 01, volume 2, equation (12.5.24)

This is the equation that defines perturbative string theory.

And this is of just the same form (cf. at worldline formalism) as the Feynman perturbation series of perturbative quantum field theory, the only difference being that the latter is more complicated: there one has to sum over Feynman diagrams with labeling for all intermediate particles (virtual particles) and with some choice of renormalization to make the integrals well defined, whereas here we simply sum over all super Riemann surfaces and that’s it. The different intermediate virtual particles as well as the renormalization counterterms are all taken care of by the higher string modes, encoded in the worldsheet CFT correlators.

There was a time in the 1960s, when quantum field theorists around Geoffrey Chew proposed that precisely such formulas for S-matrix elements should be exactly what defines a quantum field theory, this and nothing else. The idea was to do away with an explicit concept of spacetime and local interactions, and instead declare that all there is to be said about physics is what is seen by particles that probe the physics by scattering through it. This is an intrinsically quantum approach, where there need not be any classical action functional defined in terms of spacetime geometry. Instead, all there is a formula for the outcome of scattering experiments.

Historically, this radical perspective fell out of fashion for a while with the success of QCD and the quark model in its formulation as as local field theory coming from an action functional: Yang-Mills theory.

But fashions come and go, and the original idea of Geoffrey Chew and the S-matrix approach continues to make sense in itself, and it is this form of a physical theory that perturbative string theory is an example of.

More recently, the S-matrix perspective becomes fashionable also in Yang-Mills theory, with people noticing that super Yang-Mills theory and Tr(ϕ³) enjoy good structures in its scattering amplitudes which are essentially invisible in the vast summation of Feynman diagrams that extract the S-matrix from the action functional. Instead there are entirely different mathematical structures that encode at least some sub-class of scattering amplitudes (see at amplituhedron and associahedron). This has lead to increasingly close ties between the S-matrix program and the mathematical fields of geometry and combinatorics, allowing for the development of various other structures in quantum field theory that encode, for instance, the Wheeler-wavefunction of the universe (see at cosmohedron) and the UV/IR divergence of Feynman integrals (see at Feynman polytope).

On the other hand, there is also an analog of the second quantized field-theory-with-equations for string scattering: this is called string field theory, and this again is given by equations of motion. For instance the equations of motion of closed string field theory are of the form

where is the string field, is the BRST operator and is the string field star product.

(For the bosonic string this is due to Zwiebach 92, equation (4.46), for the superstring this is in Sen 15 equation (2.22)).

The string field has infinitely many components, one for each excitation mode of the string. Its lowest excitations are the modes that correspond to massless fundamental particles, such as the graviton. Expanding the equations of motion of string field theory in mode expansions (“level expansion”) does reproduce the equations of motions of these fields as a perturbation series around a background solution and together with higher curvature corrections.

Why is string theory controversial?

As a theory of the observable universe that is supposed to checked by experiment and which predicts that all fundamental particles of the standard model of particle physics are secretly, if one probes at high enough energy, excitations of superstrings, string theory is an unproven hypothesis.

Current particle accelerator technology (notably the LHC) are about 15 orders of magnitude (hence far, far) away from the energy scale at which these strings would manifest themselves directly (at least for many models in string phenomenology).

However, in principle and possibly there are indirect effects of string theory that would be probe-able with current experiment. Notably one standard scenario is that string theory is realized in a Kaluza-Klein compactification model and if so, then the properties of the fiber space (traditionally but not necessarily taken to be a Calabi-Yau manifold) on which the KK-reduction takes place determines the species and masses and interactions of the fundamental particles that we do see in experiments. Since the standard model of particle physics is pretty baroque in its field content, the hope here would be that a choice of fiber space could explain for instance that there are three generations of particles, if not even explain their couplings and masses.

For decades there has been the more or less implicit idea that the number of choices of the fiber spaces is small. That would mean – or would have meant – that string theory can make predictions not just as quantum field theory does, namely about particle scattering given the nature of the particles, but even about that nature itself, hence that it could, in the extreme case, for instance predict the mass of the elementary particles.

Notice that if so, this would be quite remarkable. For all we know, the interaction terms and masses of the fundamental particles could be just as coincidental as the number of planets in our solar system, and their distance from the sun (both of which were once speculated to follow from first principles of mathematics, which of course they do not).

While there was never any real indication that such a prediction would be possible, later the idea became widespread that it seems indeed rather unlikely. If so, then we are back to the first point, namely 15 orders of magnitude and hence impractically far away from testing string theory directly.

Then there are two possible standpoints, and they account for the controversy:

-

If you want to learn right now about the fine detail of the standard model of particle physics and just that, for instance if you are a genuine particle physicist, then string theory may give you exactly no useful information whatsoever and all time spent on it is plain wasted. The frustration over the fact that there has been the claim that string theory may directly help with GUT building and other standard model physics and that none of this turns to work out is responsible for much of the criticism. And, by all accounts, rightly so.

-

If however you feel more generally theoretically inclined, say because you are a theoretical physicist wondering about the possibilities of quantum field theory in general, or if you are even a mathematician, happy to handle theories that are not supposed have direct relation to experiment, then the situation may be very different.

String theory might be right as an assumption about the fundamental nature of the observable universe, and might at the same time still be entirely useless for experimentally based particle physics in the present age. In that case, if you are interested in experimental particle physics you should not expect much help in your lifetime. But if you are a theoretical physicist or a mathematician interested in broader conceptual questions, then it may be unwise to ignore the theory.

Does string theory make predictions? How?

String theory makes predictions much as quantum field theory does, too: the theory predicts observables once a model in the theory has been chosen.

Most every theory and model in physics has parameters and makes predictions only after sufficiently many parameters have been fixed (i.e., specified) by measuring them in experiment.

For instance Newton‘s theory of gravity says that the gravitational force of a pointlike mass is proportional to the inverse square of the distance from that mass. This is the theory, the proportionality factor (now called Newton's constant) is the free parameter that has to be fixed by experiment.

In string theory as in any other theory of physics, it is the same general principle, only that the theory is much richer. There are lots of models in string theory that make very detailed statements about the resulting physics. Moreover, many of these have good general agreement with presently observed data. One speaks of “semi-realistic models”, see at string phenomenology the discussion at Semi-realistic models in string theory. (The division line between “semi-realistic” and “realistic” here runs through very technical territory involving the fine details of string mathematics and standard model physics, and hence becomes a bit subtle. This is the reason why one sees some authors worrying about not finding a single “realistic” model while others are worried about already having found too many of them to feel comfortable with…)

The remaining problem is the following, and this is not specific to string theory but faced by any theory that provides a UV-completion of the standard model plus gravity (quantum gravity): the problem is that after parameters have been fixed this way by finding a model that reproduces the standard model reasonably accurately, all the remaining properties of the model, hence the predictions of the model, tend to be at high energies (“Planck scale”) and hence not within reach of present experiments such as the LHC.

This is a very general aspect of present particle physics: while theoretically it is fairly clear that the standard model plus gravity must have a UV-completion by something, at presently available experimental energies that standard model works rather perfectly. While this is a general fact of particle physics and model building, not special to string theory, a sociological aspect of string theory is that in the 1980s many theoreticians started to believe and claim that string theory would be better than ordinary model building in that when fully understood it would admit only very few models, such that even the parameters measured in the standard model would be predicted by the theory and some more basic parameters. More recently this hope has vanished, and much of what should be an absolute estimate of string theory is more a perception in the negative gradient of this hope curve.

But one technical speciality of string theory over QFT model building exists in either case: what in the standard model are external parameters put into a QFT Lagrangian, in string theory models are all dynamical fields of the theory instead, called moduli.

The simple familiar example to compare this to is the cosmological constant in Einstein gravity: one can either consider it as an external parameter, a constant real number coefficient in front of the volume form summand of the Einstein-Hilbert Lagrangian, or else one can consider Einstein gravity coupled to a scalar field with some potential and consider those solutions to the equations of motion where this field is almost constant to good approximation. In such a case the field itself serves as an effective cosmological constant. (This is the mechanism behind the theory of cosmic inflation, see there for more details.) Hence the theory has one less external parameter (the “cosmological constant” is not fundamentally really a constant), which has instead been replaced by a field.

In string theory this happens with all the parameters. (Except for one single constant: the string coupling constant. From the perspective of “M-theory” even that disappears. See at string theory – scales.) There is no external choice of parameter, but there remains the choice of studying “solutions to the equations of motion” (which in string theory means: choices of 2d CFTs) which might model observed physics.

That is why in string theory instead of adjusting parameters one searches solutions. Since these are also called “string vacua” (see at What is a string vacuum?), one searches vacua. The infamous term “landscape of string theory vacua” refers to attempts to understand the space of possibilities here more globally. But very little is actually known to date.

In summary: models built in string theory make predictions just as any other model in theoretical physics does. The situation is actually better in that in principle the choice of model in string theory is constrained by the theory. While the standard model of particle physics is just written to paper, when one reproduces approximations to it in string theory one has to check that various consistency conditions are satisfied which guarantee that the parameters assumed indeed do arise as configurations of the fields in the theory.

Notice that there is no a priori reason in quantum field theory that of all of the huge space of possible field theories (all local Lagrangians) the one that describes our world is a Yang-Mills gauge theory coupled to gravity – an “Einstein-Yang-Mills-Dirac-Higgs theory”. This is not a prediction of QFT but a theoretical assumption based on experimental observation, and only after this assumption is made, and only after a few dozen further parameters are fixed by hand, does the standard model of particle physics start to make any predictions at all. On the other hand, string theory does predict this general form of action functionals: the effective field theories obtained in string theory are generally gauge theories coupled to gravity. This fact is what originally led to the strong interest in string theory.

Nevertheless, in spite of this higher predictivity of string theory in principle, in practice it has not yet led to much insight that would actually affect particle physics models in practice.

Aside: How do physical theories generally make predictions, anyway?

It may be good to compare to established and (essentially) uncontroversial theories.

A good example to think of, in particular in comparison to string theory, is the theory of Einstein-gravity, also known as the theory of general relativity.

Today there is a standard model of cosmology which is a model built in the theory of general relativity, that has been experimentally tested to high accuracy (see also at cosmic inflation - Experimental evidence).

This model cannot be predicted by the theory of Einstein-gravity. It is one of many possible solutions, one point in a vastly infinitely dimensional space of solutions of general relativity. It is in turn based on the class of models known as FRW models, which enforces strong constraints on the parameters of models in general relativity. In fact in its plain vanilla version, the FRW model describes the whole universe by just three numbers, the density and pressure of homogenous matter filling the universe, and the value of the cosmological constant. This model with this choice of constrained parameters is entirely a man-made assumption, not predicted in any way from theory. But the point is that once this model has been postulated, then one can use the theory to see what it predicts about the remaining parameters, such as here the fluctuations of the cosmic microwave background radiation in a universe described by this model.

This is the general pattern of how predictions are made in physical theories:

-

posit a theory;

-

specify some of the parameters of the theory – “build a model”

-

check what the theory demands for the remaining parameters – these are the predictions of that model in that theory;

-

if experiment disagrees with the predictions then

-

see if this can be repaired by modifying the model a little, hence by varying some of the originally fixed parameters;

-

if this is impossible or gets to be too complicated to the degree of feeling “unnatural”, then either look for an entirely different model or, if all fails, modify or eventually abandon the theory and find a new one. Then repeat.

-

That this model building process is a matter of trial and error is well witnessed for instance by the early history of cosmology. Right after Einstein had found general relativity and the Einstein equations, he tried the cosmological model with non-vanishing cosmological constant, because back then he thought that would fit observation. Some later observations suggested that there is no cosmological constant, and the constant was set to zero again. Einstein, referring to his original cosmological model, spoke of his “biggest blunder”. But a few decades later, new observations show that the cosmological constant is small but non-vanishing after all, and these days we put it back into our “standard model”.

Clearly the theory does not help us predict this, otherwise there would be no reason for this repeated process of trial and error. On the other hand, once we do fix these global parameters, the theory does predict plenty of further observations in the model, which can and have been checked.

But curiously, the modern version of the standard model of cosmology with its cosmological constant (“dark energy”) and dark matter component, asserts that the vast majority of all constituents of the observable universe are in fact unobservable, except for their gravitational effect. This means: the parameters of the model can be made to fit observation, but only with the rather noteworthy consequence that the model now models something which to a large extent is not what it set out to model.

At this point there are two options: either one can take it that the standard model of cosmology predicts the existence of vast amounts of dark matter and dark energy, because only with this assumption is the model consistent with observations (but with this assumption it is very well consistent with observation). On the other hand, one might feel that with all this dark matter assumed, the model has become too contrived to be “natural”, and that instead this is a hint that the theory of Einstein gravity is not quite right. This is sociologically currently a minority position, but it is certainly intellectually a possible standpoint; it goes by the name MOND, see there for more discussion.

Similar descriptions can be given of the standard model of particle physics. This, too, makes predictions that have been tested to fantastic accuracy. But it does so only after lots and lots of parameters have been chosen. To start with, there is nothing in quantum field theory that demands that the theory of fundamental particle physics has to be a Yang-Mills gauge theory coupled to Einstein-gravity, an Einstein-Yang-Mills theory. Then there is no specific reason why the gauge group of that theory is what is observed (though there are constraints on the possible gauge groups, from quantum anomaly cancellation). There is no reason in general QFT that matter appears in the fundamental particle representations that it does (electrons, quarks, neutrinos), that it appears in three “generations” of similar structure but different mass, and no reason for all of the coupling constants in the model such as the Yukawa couplings. All these parameters have been and are being adjusted by hand, whenever observations suggest so. The latest change was the introduction of mass terms (Higgs coupling) for neutrinos and then the confirmation that there is indeed a Higgs boson sector. None of this could be derived from first principles of quantum field theory. Even for the Higgs mechanism there are plenty of potential theoretical alternatives (e.g. technicolor). All of this is part of the model building and not predicted by quantum field theory.

This is why one speaks of the standard model of particle physics and of the standard model of cosmology and not of the “standard theory”. Because the theory is fixed in both cases, Yang-Mills gauge theory and Einstein gravity. What one needs however in order to make any predictions in these theories is a choice of model.

In string theory it is just like this. One can write down models that look like the standard model of particle physics coupled to gravity at low energy, and then see what the theory predicts as further observations. The difference here is that there are many more constraints on models in string theory (string theory vacua) than there are on models in quantum field theory (for which one can write down essentially any old local Lagrangian). On the other hand, a model of string theory that fits reasonably well the standard model of particle physics (such as for instance the G₂-MSSM) typically predicts new phenomena only at energy scales not testable by present experiment. This is however necessarily so for any theory of quantum gravity, and hence a fact that one has to live with if one is going to be interested in “beyond the standard model” model building in the first place. All other proposals for “beyond the standard model” physics share this problem. Necessarily.

However, what has often been considered attractive in string theory is that despite this, string theory does reasonably constrain the vast possibility space of models in quantum field theory. While there is no reason in QFT that our world is described by Yang-Mills gauge theory and Einstein-gravity, this is precisely what models in string theory generically predict. This may not seem like a practically useful prediction given that we already assumed this since the 1915s and 1960s, respectively, by building it into our “standard models”, but from the standpoint of conceptual understanding over pure empirical measurement it might be regarded as a suggestive aspect that in string theory the existence of Einstein-Yang-Mills theory can be derived from a more fundamental theory, in the vast space of other possible local Lagrangians. Of course the latter can also be said for other proposals, such as the spectral action principle. What string theory offers on top of such other proposals is that it derives Einstein-Yang-Mills theory and provides a UV-completion for it. The trouble is just that, by the nature of UV completions, these concern the behaviour at higher energy scales, and in this case at higher energy scales than can conceivably be measured in the near future. This is a general problem of quantum gravity phenomenology and as such not specific to string theory.

However, string theory has potential effects on at least the conceptual understanding of quantum field theory beyond direct measurement of high energy effects. See at string theory results applied elsewhere for more on this.

Is string theory testable?

This question overlaps with the question How does string theory make predictions?, but it maybe deserves its own answer.

In both QFT as well as string theory one “builds models” within the general theory and tests these, as far as their predictions are about available experiments. Loads of string theoretic models and non string-theoretic models have been excluded by LHC data in 2012, when the experiment ruled out more and more of the possible parameter space for one global spacetime supersymmetry somewhere at the electroweak symmetry breaking scale (see also Does string theory predict supersymmetry below). So all this was testable, has been tested and turned out to be wrong.

So model building in string theory is much as in QFT. When a model is ruled out, it does not necessarily mean that string theory is ruled out or that QFT is ruled out, but it means that the possibilities for adjusting the free parameters in the theory are being reduced.

To see that this is a common scientific process, it may help to look at some important historical examples. For instance shortly after Einstein proposed the theory of gravity now named after him, he proposed a cosmological model within that theory. Since he thought back then that the observable universe was static, he chose a free parameter of his theory, the cosmological constant, to take just such a value that the resulting equations of motion fitted his expectations. But just shortly afterwards it became clear that this is wrong, that instead the observable universe is expanding. Was Einstein’s theory wrong? No, his model within the theory was wrong. (He famously called it his “biggest blunder”, but it’s common for models to be ruled out. It’s fundamentally a trial and error process, after all. ) The model was discarded and quickly a new model was “built”, the now standard FRW model, still within Einstein’s theory. That has nicely fitted all data since, with slight adjustments, and so we are fond of it and call it the standard model of cosmology.

This kind of model-building process happens within string theory, too: by iteration the models are being tested, discarded or adjusted, tested again, etc.

Actually, string theory model building is more constrained than plain QFT model building, due to the fact that at the heart of it there are no free parameters, since all parameters are instead fields of the theory, as mentioned before in How does string theory make predictions?. So ultimately it gives more, not fewer, reasons to discard a model already on theoretical grounds. There are QFT models which cannot be realized in string theory, because the constraints on the parameters are stronger in string theory, because string theory is not just any old effective field theory that can be further adjusted as the energy scale is increased, but is already a UV-completion. It either makes sense at all energies, or not at all. (A practical problem here is that in computations usually lots of approximations are introduced which are not always guaranteed to be viable. For instance nobody really has a good theoretical handle if all the points in the alleged landscape of string theory vacua really are solutions to the theory. They have all been checked to be so only in some approximation.)

An example of how string theory is more constrained in its model building than effective QFT keeps the community busy since 1998: then it was observed experimentally that the cosmological constant of the observable universe these days is small but positive. But accommodating a positive cosmological constant into string theoretic models is harder than negative cosmological constant. So this observation tested a large region of string model building and found it to be wrong. But as for the example of Einstein’s “biggest blunder” above, even with all these models ruled out, the theory is still not ruled out (maybe one day with more observations it will!) Instead, as in the historical example, the failure of the favorite models lead to new theoretical activity in understanding the theory and its remaining possible models. All this talk about “metastable vacua”, etc since in string theory originates in this experimental observation in 1998.

On the other hand, no other theoretical framework was equally tested by this astronomical observation. In all other existing theoretical frameworks you simply take a pen and change the sign of the cosmological constant by hand. The theory does not control it, it’s a free parameter. So it seems justifiable to say that string theory is actually more testable than other existing theoretical frameworks. Of course to appreciate what this means one has to pay attention to what it means to test a theory by testing all its parameter space of models, as illustrated by the Einstein “biggest blunder”-example.

Is string theory causal, given that it is not local on the string scale?

In an S-matrix theory such as perturbative string theory (see above at What is string theory) the property of causality is embodied by the fact that the S-matrix shows certain analyticity features. (Therefore the S-matrix approach to quantum field theory is often referred to as “the analytic S-matrix”).

Since, as opposed to a fundamental particle, the string is extended, at the string scale string theory is not given by a local field theory. This superficially seems to suggest that at such scales also causality might be violated in string theory. However, computation shows that the string scattering S-matrix comes out suitably analytic and causal (e.g. Martinec 95).

A detailed analysis for how this comes about has been given in (Erler-Gross 04). They write:

Perhaps then it comes as a surprise that critical string theory produces an analytic S-matrix consistent with macroscopic causality. In absence of any other known theoretical mechanism which might explain this, despite appearances one is lead to believe that string interactions must be, in some sense, local.

and

We find that string theory avoids problems with nonlocality in a surprising way. In particular, we find that the Witten vertex is “local enough” to allow for a nonsingular description of the theory which is completely local along a single null direction.

and

unlike lightcone string field theory, it is clear that cubic string field theory at least has a local limit where all spacetime coordinates are taken to the midpoint. We investigate this limit with a careful choice of regulator and show that at any stage the theory is nonsingular but arbitrarily close to being local and manifestly causal. We believe that the existence of this limit, though singular, must account for the macroscopic causality of the string S-matrix. Thus, string theory is local enough to avoid the inconsistencies of a theory which is acausal and nonlocal in time, but is nonlocal enough to make string theory different from quantum field theory

Does string theory predict supersymmetry?

To understand this question and its answer, it is important to know that in general symmetries in physics (and in mathematics) come in a local and in a global flavor. For instance the theory of gravity is a theory which has as a local symmetry the Poincaré group, including the Lorentz group. But any model of the theory – a spacetime – may or may not have global Lorentz symmetry (“Killing vector fields”). In fact, the generic solution to the Einstein equations has no global Lorentz symmetry left. Indeed, global Lorentz symmetry of spacetime with all matter and force fields in it would mean that the world looks the same if we arbitrarily translate in some direction, or arbitrarily rotate in some plane. It would be rather bizarre to live in a spacetime with such a property!

(Mathematically the distinction is this: given a coset space , then the corresponding Klein geometry has global -symmetry, while the corresponding Cartan geometries have local -symmetry.)

Now supersymmetry refers to a super Lie group extension of the Lorentz group. Here the theory of supergravity has local supersymmetry just as Einstein gravity has local Lorentz symmetry, but the general model in supergravity has no global supersymmetry left. This is just as unlikely as, and directly analous to, a spacetime having a global translation symmetry.

(Mathematically this is now the situation of super Cartan geometry.)

Contrary to that, local supersymmetry is rather generic in low dimensions. For instance the worldline theory of any spinning particle – such as an electron – is locally supersymmetric. (See the references here.) So local supersymmetry has been experimentally verified for the observable universe when fermions were first observed to exist, which is since the Stern-Gerlach experiment.

Similarly, if one proceeds from the worldline formalism for spinning particles to the worldsheet theory of spinning strings, the most natural choice of Lagrangian for fermions on the worldsheet automatically satifies local supersymmetry. This is how supersymmetry was found historically: people wrote down the obvious action functional for spinning strings which was just intended to produce fermions and then it was noticed that this exhibits a curious extra “super”-symmetry. Ever since the spinning string is called the superstring.

The miracle that then happens is that while the second quantization of spinning particles (which is fermionic quantum field theory) does not necessarily itself exhibit local supersymmetry, the second quantization of spinning strings (which is string theory with fermions) does itself also exhibit local supersymmetry: the effective field theory induced by spinning strings is not just Einstein-Yang-Mills-Dirac theory, but is locally supersymmetric in that it is higher dimensional supergravity.

(This result is known as the Goddard-Thorn no-ghost theorem with GSO projection.)

So: string theory implies that if there are fermions at all, then there is local supersymmetry, hence supergravity.

On the other hand, any model in string theory may or may not retain global supersymmetry at some energy scale, after spontaneous symmetry breaking.

In fact the generic model has a priori no reason to preserve any low energy global supersymmetry below the Planck scale at all (see e.g. Giudice-Strumia 11, p. 1-2), just as the generic solution of Einstein's equations does not preserve any Lorentz group symmetry. The condition that a Kaluza-Klein compactification of 10-dimensional supergravity to 4d exhibits precisely one global supersymmetry is equivalent to the compactification space being a Calabi-Yau manifold. While this is a famous condition that has been extensively studied (see at supersymmetry and Calabi-Yau manifolds), nothing in the theory seemed to require KK-compactification on Calabi-Yau manifolds. These were originally considered because for phenomenological reasons it is (or was) expected that our observed world exhibits global low-energy supersymmetry.

However, recently arguments for a theoretical preference for supersymmetric compactifications have been advanced after all (FSS19, Sec. 3.4, Acharya 19).

The role of local supersymmetry (supergravity) which superstring theory does predict is quite different from that of low energy global supersymmetry. Notice that as soon as there is a fermion in the world it follows that spacetime is described by supergeometry, since fermion field are necessarily formalized by anticommuting functions in the Lagrangian defining any prequantum field theory containing them. Now supergeometry alone does not mean that there is an action of the super Poincaré Lie algebra on anything, which is what is called supersymmetry.

On the other hand, in low worldvolume dimension this tends to be inevitable. For instance the worldline theory of any spinning particle (such as electrons) necessarily has worldline supersymmetry, see at spinning particle - Worldline supersymmetry and at spinning particle - Worldline supersymmetry - References.

Similarly, the standard sigma-model worldsheet action functional of the spinning string was not originally intended to be supersymmetric, but just so happens to come out this way. The special phenomenon as opposed to the superparticle is that the worldsheet supersymmetry of the string implies that its second quantization effective field theory is also locally supersymmetric, hence is a theory of supergravity.

What is a string vacuum?

In perturbative quantum field theory a vacuum state is the information needed to turn a product of field observables such as into a function (or rather: generalized function/distribution) of the insertion points any , namely the n-point function (here 2-point function, also called the Hadamard propagator)

which may be regarded as the probability amplitude for a quantum in state at spacetime point to turn into a quantum in state at spacetime point , in the given state that the fields are in, which is defined thereby (see at state in AQFT).

In the worldline formalism of field theories these propagators arise from a 1-dimensional field theory on the “worldline” of (virtual) particles running from to .

Now by the very definition of perturbative string theory, these particles are replaced by strings whose dynamics is now encoded in a 2d field theory on the worldsheet of strings, specifically a 2d superconformal field theory (2d SCFT) of central charge 15. Hence now it is the 2d SCFT which defines the vacuum state that the perturbative string theory is in. This is then called a perturbative string theory vacuum.

In practice full 2d SCFTs are hard to construct, and often one considers them by perturbation theory of a “sigma-model” which is defined by a spacetime manifold equipped with extra fields (e.g. the B-field etc.). It turns out that to low order these background field configurations that define sigma-model 2d SCFTs are given by solutions to equations of motion of supergravity theories (e.g. type II supergravity for type II string theory, etc.)

Therefore often such supergravity solutions equipped with some extra data that makes them consistent CFT backgrounds at higher order are referred to as vacua for string theory. But this is in general a coarse approximation. The full vacua are the full 2d SCFTs that define the worldsheet theory of the string.

The collection of all string vacua, possibly subject to some assumptions, has come to be called the landscape of string theory vacua. See at What does it mean to say that string theory has a landscape of vacua?

How/why does string theory depend on “backgrounds”?

To answer this question one needs – as discussed at What is string theory? – to distinguish between perturbative string theory and non-perturbative string theory.

Perturbative string theory, being a variant of traditional perturbation theory in quantum field theory, is by construction a perturbation about a background, just as any perturbation series is.

To stick with the (close) analogy to Taylor series mentioned before in What is string theory?: if the full object of study is a smooth function on the real line, then a “perturbative” approximation to this by a Taylor series involves a choice of point on the real line around which the Taylor series is developed. The series itself represents the original function restricted to the formal neighbourhood of that point.

This example also serves to illustrate in which sense a perturbation series “depends” on a choice of background: for a given smooth function and for two points on the real line that lie within the convergence radius of the Taylor series of that function around the respective other point, the expansion does not depend on the “choice of background” in the sense that the value of one series evaluated at a given point equals the value of the other series evaluated at the same point. The only restriction to this statement is that some points may lie outside of the convergence radius.

For QFT perturbation series we have essentially the same situation: the correlators of the theory are expressed as formal power series in the coupling constants of the theory and in Planck's constant, which are the formal approximations to the true non-perturbative correlators expanded about zero coupling and vanishing Planck’s constant. At that 0-point the theory is non-interacting and “classical”, meaning that this is the point of a solution to the classical equations of motion of the non-interacting theory. Such a solution is also called a vacuum or a background of the quantum theory. Notably in theories containing gravity (such as string theory), such a background involves a solutions to Einstein's equations, hence involves fixing a spacetime manifold on which all further perturbative quantum fields propagate.

By the above logic, while the specific perturbation series depends on the choice of this classical solution, hence the choice of “background” or of vacuum, this dependency is not a property of the underlying non-perturbative theory but is a defining property of what it means to consider a perturbative approximation. (The subtlety being that for all QFTs of interest the radius of convergence of that formal series is necessarily 0, see the discussion at Isn’t it fatal that the string perturbation series does not converge? )

By design, all this applies also to perturbative string theory.

As mentioned before, there is the idea that perturbative string theory is indeed the perturbative approximation to an as-yet unknown non-perturbative string theory. To the extent that this is true, the dependence of the string perturbation series on the choice of “background” should be of the same superficial nature as it is for traditional perturbative QFT. But this remains a conjecture.

Consistency arguments for this speculation have been given in (Witten xy). A theoretical framework for formalizing these questions is string field theory, in the context of which much of this has been formalized (…).

For more on what perturbative string theory around a given such background looks like, see also the question How is string theory related to the theory of gravity?

Did string theory provide any insight relevant in experimental particle physics?

Yes. One curious aspect of string theory is that independently of its role as a source for models in particle physics, it provides connections in the space of all possible quantum field theories: lots of different quantum field theories (many of them highly unrealistic as phenomenology goes, but interesting for theoretical investigations) appear as different limits and special cases inside string theory, and their embedding into a single framework this way explains many unexpected relations between them. One of this has led to recent progress simply in computational tools of perturbation series. LHC physicists claimed that without the insight from string theory, the evaluation software used at the LHC could not have been precise enough to see the Higgs in the data.

Details on this are linked to at

This is maybe the example most directly related to experimental physics, but there are various other relations (“dualities”) between QFTs learned from or better understood with string theory. (Seiberg duality for instance, long list will go here…)

Does string theory tell us anything about cosmology, such as the Big bang or cosmic inflation?

No. Looking back at the answer to What is string theory? we have that the only thing really defined is perturbative string theory – and quantum perturbation theory is clearly insufficient for discussion of strongly coupled phenomena such as cosmological phenomena (as opposed to those tiny excitations studied in particle accelerators).

More precisely: given that perturbative string theory does describe classical gravitational backgrounds with small quantum fluctuations about them, and given that this is already all that traditional cosmology considers, certainly all of traditional cosmology can sensibly be modeled in string theory. But perturbative string theory cannot say much about the long-expected strong quantum corrections to gravitational effects in quantum gravity.

This hasn’t stopped people from making lots of speculations, and there is something like a “field” called “string cosmology” in that you find authors writing about this, giving talks and lectures about it. But this is a bit like a soccer match with a ping-pong ball.

What would be needed here is an understanding of non-perturbative string theory.

On the other hand, in theories of supergravity such as string theory, there are some observables that are independent of the coupling constant (called “protected”): the BPS states. If one can compute such observables in perturbation theory and then has an idea of what these correspond to as the coupling constant is set to a finite value, then one can know the value of the corresponding observable in the non-perturbative theory without even knowing that non-perturbative theory itself. This is the mechanism by which perturbative string theory does make statements about black hole entropy, where black holes by their very nature are strongly coupled gravitational configurations. More on how this works is at black holes in string theory.

Since the singularity involved in back holes is a similar kind of singularity as that involved in the big bang one might think that some analogous method is useful in the latter case. But if so, it has not surfaced so far.

What is the relationship between string theory and quantum field theory?

Recall from some of the previous answers:

-

Perturbative string theory is defined to be the asymptotic perturbation series which are obtained by summing correlators/n-point functions of a 2d superconformal field theory of central charge -15 over all genera and moduli of (punctured) super Riemann surfaces.

-

Perturbative quantum field theory is defined to be the asymptotic perturbation series which are obtained by applying the Feynman rules to a local Lagrangian – which equivalently, by worldline formalism, means: obtained by summing the correlators/n-point functions of 1d field theories (of particles) over all loop orders of Feynman graphs.

So the two are different. But for any perturbation series one can ask if there is a non-renormalizable local Lagrangian such that its Feynman rules reproduce the given perturbation series at sufficiently low energy. If so, one says this Lagrangian is the effective field theory of the theory defined by the original perturbation series (which, if renormalized, is conversely then a “UV-completion” of the given effective field theory).

Now one can ask which effective quantum field theories arise this way as approximations to string perturbation series. It turns out that only rather special ones do. For instance those that arise all look like quantum anomaly-free Einstein-Yang-Mills-Dirac theory (consistent quantum gravity plus Yang-Mills gauge fields plus minimally-coupled fermions). Not like phi^4 theory, not like the Ising model, etc.

(Sometimes these days it is forgotten that QFT is much more general than the gauge theory plus gravity plus fermions that is seen in what is just the standard model of particle physics. QFT alone has no reason to single out gauge theories coupled to gravity and spinors in the vast space of all possible anomaly-free local Lagrangians.)

On the other hand now, within the restricted area of Einstein-Yang-Mills-Dirac theories, it currently seems that by choosing suitable worldsheet 2d CFTs one can obtain a large portion of the possible flavors of these theories in the low energy effective approximation. Lots of kinds of gauge groups, lots of kinds of particle content, lots of kinds of coupling constants. There are still constraints as to which such QFTs are effective QFTs of a string perturbation series, but they are not well understood. (Sometimes people forget what it takes to defined a full 2d CFT. It’s more than just conformal invariance and modular invariance, and even that is often just checked in low order in those “landscape” surveys.) In any case, one can come up with heuristic arguments that exclude some Einstein-Yang-Mills-Dirac theories as possible candidates for low energy effective quantum field theories approximating a string perturbation series. The space of them has been given a name (before really being understood, in good tradition…) and that name is, for better or worse, the “Swampland”.

Isn’t it fatal that the string perturbation series does not converge?

The string scattering amplitudes computed in string perturbation theory are thought to be term-wise (loop-wise, hence for each genus of the Riemann surface worldsheets) finite. Nevertheless, the sum over all these contributions diverges. Does this mean that perturbative string theory is unrealistic from the get go?

No. On the contrary, the Feynman perturbation series of every QFT of interest is supposed to have vanishing radius of convergence (Dyson 52) and be just an asymptotic series. Because the expansion parameter is the coupling constant and if the series had a finite radius of convergence, there would be also negative values of the coupling for which the correlators are convergent. See at non-perturbative effect for more.

So the non-convergence of the string perturbation series is just as it should be in QFT: a perturbation series in quantum field theory is generally an asymptotic series, meaning that it diverges but every finite truncation of it produces a sum that approximates the “actual” value (the actual correlation functions) in a controlled way (as explained at asymptotic expansion).

The important property of the string scattering amplitudes is rather that they (plausibly) come out termwise finite (proven so for bosonic string theory and the first orders of superstring theory), which means that it is already renormalized: the higher string modes provide the natural counterterms for the renormalization (see also at How do strings model massive particles?).

So the convergence/divergence of the string perturbation theory is of the same kind as for instance in the QCD that appears in the standard model of particle physics. For more on this phenomenon see at perturbation theory – divergence/convergence and especially see also the references there and see at non-perturbative effect.

How do strings model massive particles?

In string phenomenology, each fundamental particle species corresponds to a different excitation mode of one single species of fundamental string. However, a subtle aspect to keep in mind here is that all fundamental particles are fundamentally massless and receive a – comparatively low – mass only via a Higgs mechanism.

In string phenomenology therefore all fundamental particles correspond to ground state excitations of strings. Indeed, the ground state excitations of superstring are massless (while that of the bosonic string in fact has negative mass squared and hence models a tachyon particle). This is a nontrivial statement due to the nature of quantum harmonic oscillators and follows from a careful analysis of quantum effects.

For instance, in simple situations the gauge field particles of spin 1, such as the photon, are modeled by the ground state excitations of the open string. Due to quantum effects even the ground state oscillates a little, and the orientation of this oscillation accounts for the polarization degrees of freedom of the photon.

Every excited mode of a string however corresponds to a particle of comparatively huge mass, not meant to be close to any particle mass ever observed. So the infinite tower of higher string excitations is not meant to be directly observable in string phenomenology. Nevertheless, these massive particles have a crucial role to play: their appearance as virtual particles in string scattering amplitudes is what renders these probability amplitudes loopwise finite: they are the counterterms that exhibit perturbative string theory as a renormalized perturbation theory. See also the discussion at Isn’t it fatal that the string perturbation series does not converge?.

How is string theory related to the theory of gravity?

The technical statement is that the effective quantum field theory defined by the string scattering amplitudes is a supergravity version of Einstein-Yang-Mills theory (namely heterotic supergravity or type II supergravity).

This means the following:

The string scattering amplitudes between given incoming and outgoing asymptotic quantum states of free strings, are probability amplitudes abstractly defined by summing the correlation function of a 2-dimensional SCFT over all super Riemann surfaces with given punctures.

One tends to think of this sum heuristically as computing the superposition of probability amplitudes of all possible ways that the incoming strings can come in, interact with each other in a given background spacetime, and come out of this scattering process again. But this heuristic idea can be formalized: we can ask if there is an ordinary perturbative quantum field theory such when we compute its scattering amplitudes by the usual Feynman diagram rules of expansion about a solution to the equations of motion (e.g. Einstein's equations), the result coincides with the string scattering amplitudes at low energy. If one finds such a quantum field theory, one calls it the effective quantum field theory which effectively approximates the string dynamics at low energy. (See also above Why/how does string theory depend on “backgrounds”?.)

In words this means: the “stringy” process defined by the string perturbation series looks in good approximation at low energy as such-and-such interactions of such-and-such particles.

And if one now computes what this effective quantum field theory defined by the string scattering amplitudes is, then one finds that it generically is a gravity coupled to Yang-Mills theory in a supergravity version of Einstein-Yang-Mills theory.

Notice that an effective quantum field theory (and this one is no exception) is not in general renormalizable, meaning that to a given energy scale one has to add higher order terms to it (counterterms) to make it well defined. Here it is precisely the full string perturbation series that provides these counterterms: the higher-energy interactions of the string provide the renormalization of its effective low energy theory of gravity+-Yang-Mills theory. One says that the string perturbation series provides a UV-completion for Einstein-Yang-Mills theory (hence for gravity, or rather for supergravity).

By designs of what scattering amplitudes are, all this are statements in perturbation theory and in perturbation theory. Notice that this is not some secret bug in string theory, but is so by the very definition of perturbative string theory and perturbation theory.

The fact that perturbatively perturbative string theory is a UV-completion of perturbative quantum gravity may of course make one want to find something like non-perturbative string theory. While there are some hints as to what this might be (these days there are many hopes that the AdS-CFT correspondence provides a non-perturbative extension of the description of quantum gravity by string theory), this non-perturbative description remains unclear, in stark contrast to perturbative string theory which is a rather well-defined and conceptually well-understood.

Do the extra dimensions lead to instability of 4 dimensional spacetime?

The parameters of size and shape of the compactified dimensions in string theory, and in fact in any Kaluza-Klein compactification, are called “moduli”. Since they are part of the higher dimensional metric, they are components of the higher dimensional field of gravity and hence are dynamical fields that evolve. The problem of their stability, hence the question whether there are dynamical mechanisms that make for instance the size of the compactified space remain stably at a given value, is famous as the problem of moduli stabilization in string theory.

This problem used to be open until around 2002. Then it was realized that vacuum expectation values (VEVs) of the higher form fields (“fluxes”) present in string theory generically induce effective potentials for moduli that may stabilize them, at least for fluctuations that preserve the given special holonomy (CY-compactifications of string theory or G₂-holonomy compactifications for M-theory).

For type IIB string theory/F-theory this was argued in the influential article KKLT 03. An analogous moduli stabilization mechanism was also argued for M-theory on G₂-manifolds by Acharya 02. It is the counting of all the many possible ways of stabilizing moduli via fluxes in type IIB that led to the now infamous discussion of the landscape of type II string theory vacua (see also below). In any case, there seems to be no lack of solutions of the stability problem.

What does it mean to say that string theory has a “landscape of solutions”?

Being a perturbation theory (see What is string theory? above), there are perturbative string scattering amplitudes for each solution of the equations of motion of the effective background theory of (super)-Einstein-Yang-Mills-Dirac-Higgs theory (see also How/why does string theory depend on backgrounds? above).

In fact, more precisely, a perturbative string theory vacuum for string perturbation theory is a choice of super-2d CFT of central charge 15 (see What is a string vacuum?), and each of them induces such an effective background (by a mechanism indicated at 2-spectral triple). This imposes considerably more constraints than one has to solve to find a solution to just Einstein-Yang-Mills equations (for instance “modular invariance” of the 2d theory, etc.). As a result, it is considerably harder to find a backround string vacuum for string theory than for its non UV-complete non-renormalized effective Einstein-Yang-Mills-Dirac-Higgs theory.

Due to these strong constraints, there had for many decades be a wide spread hope among some (many) string theorists that these constraints are in fact so strong as to maybe essentially uniquely single out one small class of vacua. And since the vacua in a KK-mechanism theory like string theory determine the fundamental particle content in the low dimensional effective QFT, that would have meant that under maybe mild assumptions string theory would maybe even predict the particle content of the standard model of particle physics, to some extent.

There had never been a formal argument for this hope, but this hope has influenced both the community and its public perception. Then in the 1990s (only) string theorists began to start solving some of these extra constraints that string theory imposes for consistent vacua. Among these constraints is notably the phenomenological constraint that the “moduli” of the KK compactification, hence the dilaton field and its many cousins, become massive. For if they were fundamentally massless as the main particles in the standard model of particle physics, then they would have had shown up in accelerator experiments (such as these days the LHC) which however they do not.

One way to deal with this is to consider models in type II string theory which have nontrivial RR-field configurations in the internal space. It turns out that the periods of the corresponding field strengths over cycles in the compact space induce a potential energy for some or all of the moduli fields, hence a mass for them in perturbation theory, so that by choosing these “fluxes” appropriately “all moduli can be stabilized”.

By a kind of Dirac charge quantization condition, the periods of these “flux fields” have to be integers and hence form a discrete space, as opposed to the usual continuous spaces of solutions of field theories. Moreover, due to some other constraints the potential energy which they induce cannot be too large, so that the admissible choices of periods for a flux field over some internal cycle is some finite number.

Hence given some internal manifold, the number of choice of models with fluxes is the product of some finite number, taken over each of the (still finite) classes of cycles.

Traditionally one considered KK compactification on real 6-dimensional Calabi-Yau manifolds (see at supersymmetry and Calabi-Yau manifolds). Since these are generically topologically complicated, they have comparatively large numbers of cycles. In a hand-waving estimate of the numbers to expect here, somebody assumed that the number of possible values of flux for each cycle is maybe about 10, and that the typical Calabi-Yau manifold has maybe about 500 classes of cycles. With these numbers accepted, there would be many ways to choose the flux fields in such a flux compactification of string theory.

While this number is large, for appreciating this number it is important to notice that typically the spaces of solutions to a physical theory, such as Einstein-Yang-Mills-Dirac-Higgs theory, not only have infinitely many points, but typically are highly infinite dimensional continuous spaces. In view of this even a large finite number of solutions still makes a very small space of solutions, compared to the generic spaces of solutions that one traditionally deals with in physics.

Nevertheless, due to that latent and long-time hope that maybe the full constraints on string theory vacua are so strong such as to only leave a handful, this number (obtained with plenty of assumptions and hand-waving and estimating, as it were) gave rise to a wide-spread feeling that the space of vacua of string theory is “vast”, and the word landscape of string theory vacua became popular and accepted for this space – for what among sober mathematicians would just have been called the moduli space of 2d SCFTs.

Ever since the public discussion shows a strong preference towards being worried about a “landscape problem” of string theory.

One might argue that instead of worrying much about a hand-waving statement which even at face value is “better” than what one sees in generic field theories, energy might more fruitfully be invested into getting a better technical handle of what the moduli space of 2d SCFTs – and hence the landscape of string theory vacua – actually is.

For instance the authors of one of the few research programs these days to actually study the subtle nature of string theory backgrounds

- Jacques Distler, Daniel Freed, Gregory Moore, Orientifold Précis, in Hisham Sati, Urs Schreiber (eds.), Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Field and Perturbative String Theory, Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics, volume 83 AMS (2011) (arXiv:0906.0795)

write on page 9 of their accurate study of orientifold backgrounds:

We hope that our formulation of orientifold theory can help clarify some aspects of and prove useful to investigations in orientifold compactifications, especially in the applications to model building and the “landscape.” In particular, our work suggests the existence of topological constraints on orientifold compactifications which have not been accounted for in the existing literature on the landscape.

In summary then, the landscape of string theory vacua is essentially the moduli space of 2d SCFTs. As such it is a mathematically rich and subtle object about which almost nothing precise is known at the moment. The hand-waving arguments about the nature of corners of this space, whether correct or not, do not actually point to a problem in string model building that would be worse than in model building in other theories. On the contrary, in as far as parts of the “landscape” are indeed finite sets, then no matter how large that finite number is, it is still vastly smaller than the cardinality of the infinite-dimensional spaces of solutions of a typical theory of physics.

Is string theory mathematically rigorous?

The core of perturbative string theory has a mathematically rigorous formulation. In fact much of mathematical physics and mathematical insight into quantum field theory as such has been gained from the study of the low-dimensional QFTs that constitute the worldvolume theories of the string and the various branes. For instance the axiomatization of QFT in the “FQFT” flavor (roughly dual to the AQFT picture) historically originates in insights gained in the study of (topological) string (namely the Moore-Seiberg axioms). On the other hand, the attempted implementations and applications of core string theory are vast and numerous, and when it finally comes to string phenomenology the usual level of rigor is just that common among practicing quantum field theorists. On the far end, deep aspects of string theory that are felt by many researchers to be of metaphysical relevance, such as the “landscape of string theory vacua” (see above) have led and are leading to speculations that are not anymore backed up by any disciplined reasoning.

More in detail:

The quantization of the string sigma-model may be obtained cleanly via the mathematical sound process of geometric quantization, see the references at string – Symplectic geometry and Geometric quantization. The famous Weyl anomaly of the string is formally understood in terms of anomalous action functionals, see for instance (Freed 86 2.). Various other obstructions to quantization (quantum anomalies) in the background fields for the string sigma-model such as notably the Freed-Witten-Kapustin anomaly, have been understood in fine detail in terms of obstructions in differential cohomology, see for instance (Distler-Freed-Moore 09).

Particularly well analyzed are the two special sectors of first quantized string theory, that of rational conformal field theory, which contains the example of strings propagating on Lie group manifolds – the Wess-Zumino-Witten model; as well as the example of topological strings. Rational conformal field theories indeed stand out as one non-trivial and rich class of QFTs which have been subject to complete mathematical classification (in the same sense in which mathematicians for instance do the classification of finite simple groups). For details on this classification see at FRS formalism.

For the topological string much more is true. The topological string has effectively become a subject in pure mathematics, with its rigorous axiomatization via the TCFT version of the cobordism hypothesis-theorem, its formulation as mathematical homological mirror symmetry, its relation to geometric Langlands duality etc. Here it is maybe noteworthy that all this mathematical insight into string physics rests on homotopy theory and higher category theory (the cobordism hypothesis, to wit, which governs the topological string, is a theorem in pure (infinity,n)-category theory). See also the question How does string theory involve homotopy theory, higher geometry and higher category theory?.

But the FQFT-axiomatics that serves to mathematically formalize the topological string is not restricted to the topological sector, it also applies to the physical string. For instance Huang’s theorem shows that the familiar description of physical string via vertex operator algebra is an instance of the FQFT-formalization. Indeed, in FRS formalism these two formalizations, vertex operator algebras (via their modular tensor categories of representations, and TQFT combined via the rigorous AdS3-CFT2 and CS-WZW correspondence give the classification of rational CFT). (In particular this says that in this low dimensional holography and AdS-CFT duality is rigorous, of course this is far, far from true in higher dimensions.) This means that the rigorous quantization of the string in these approaches is “holographically” encoded in the quantization of Chern-Simons theory: the space of quantum states of 3d Chern-Simons theory is identified with the space of conformal blocks (correlators) of the string WZW-model on this surface. Here quantization of Chern-Simons theory is one of the best analyzed quantizations of a non-trivial rich QFT.

In summary this is a level of rigour with which the worldsheet 2d QFT of the string is understood which is well beyond of what one typically encounters for non-trivial interacting (non-free) QFT. And this is full non-perturbative quantum field theory (on the worldsheet!), not just the approximation in perturbation theory.

From here on, also string field theory (its action functional, that is), has a completely rigorous formulation in terms of operads and L-infinity algebras (Lie n-algebras for ).

Of course what does not have a rigorous formulation, not even a good non-rigorous formulation, is any conjectured non-perturbative (in spacetime!) completion of string theory (M-theory). But this is clear from the answer above at What is string theory.

A snapshot of the state of the art of rigorous foundations of string theory as of 2011 is in Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Field and Perturbative String Theory.