nLab quantum Hall effect

Context

Quantum systems

-

quantum algorithms:

Topological physics

Topological Physics – Phenomena in physics controlled by the topology (often: the homotopy theory) of the physical system.

General theory:

In metamaterials:

For quantum computation:

Contents

- Idea

- Hall effect and Hall resistivity

- Integer quantum Hall effect

- Fractional quantum Hall effect

- Composite particle picture

- Properties

- Related concepts

- References

- General

- Integral quantum Hall effect

- Fractional quantum Hall effect

- Abelian Chern-Simons for fractional quantum Hall effect

- Quantum Hall effect via non-commutative geometry

- Anyons in fractional quantum Hall systems

- Observation of anyons in fractional quantum Hall systems

- Superconducting defect anyons in FQH systems

- Supersymmetry in fractional quantum Hall systems

- In string/M-theory

Idea

In short:

At sufficiently low temperature, in effectively 2-dimensional electron systems (such as at semiconductor heterojunctions) quantum effects change the nature of the classical Hall effect, in two ways:

-

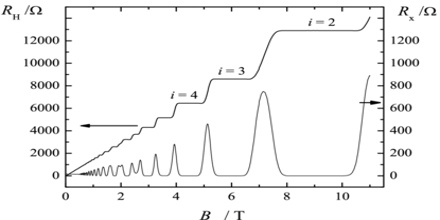

in the integral quantum Hall effect, quantization of the energy into Landau levels of electrons (that are circulating in a transverse magnetic field while confined to a plane) causes the Hall resistance — which classically increases linearly with increasing external magnetic field — to instead intermittently form constant “plateaus” as the Landau levels get “filled” by electron states,

-

in the fractional quantum Hall effect, strong external magnetic field causes these Landau levels to be filled only partially and the strongly Coulomb-coupled electrons to form bound states “with” magnetic flux quanta that may exhibit effective fractional charge and, apparently, “fractional statistics” (anyonic braiding behaviour).

In a tad more detail:

Quantum Hall effect. In a 2D sheet of conducting material threaded by magnetic flux density

the energy of electron quantum states is quantized by Landau levels as

where each level comprises one state per magnetic flux quantum:

Integer quantum Hall effect. Fermi theory of idealized free electrons hence predicts the system to be a conductor away from the energy gaps between a completely filled and the next empty Landau level, hence away from the number of electrons being integer multiples , of the number of flux quanta, where longitudinal conductivity should vanish.

This is indeed observed and is called the integer quantum Hall effect — in fact the vanishing conductivity is observed in sizeable neighbourhoods of the critical filling fractions (“Hall plateaux”, attributed to disorder effects).

Fractional quantum Hall effect. But electrons in a conductor are far from free. While there is little to no theory for strongly interacting quantum systems, experiment shows that the Fermi idealization breaks down at low enough temperature, where longitudinal conductivity decreases also in neighbourhoods of certain fractional filling factors , prominently so at for .

The heuristic idea is that at these filling fractions the interacting electrons form a kind of bound state with flux quanta each, making “composite bosons” that as such condense to produce an insulating mass gap, after all.

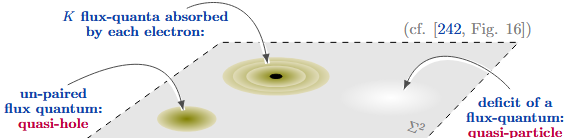

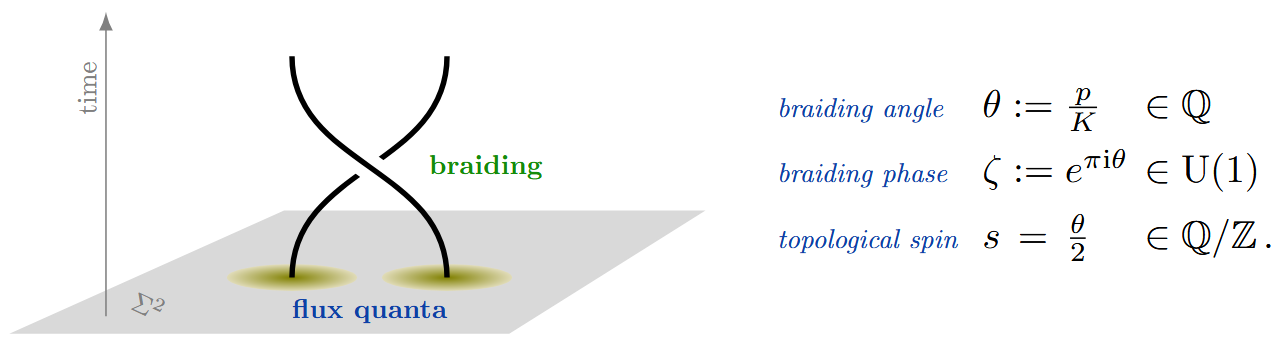

Anyonic quasi-particles. But this suggests that in the Hall plateau neighbourhood around such filling fraction, there are unpaired flux quanta each “bound to” one th of a (missing) electron: called “quasi-particles” (“quasi-holes”).

These evidently have fractional charge and are expected to be anyonic with pair exchange phase . There is claim that this anyonic phase has been experimentally observed (see below).

Hall effect and Hall resistivity

The setup of any Hall effect is a plane sheet of (semi-)conducting material placed in a transverse magnetic field (constant across the plane, directed perpendicular to it).

The classical Hall effect is the phenomenon that a voltage applied along the conducting sheet in some direction – to be called the -direction – induces a Hall voltage in the perpendicular direction – to be called the -direction – across the conducting sheet.

The cause of this effect is the Lorentz force, exerted on the electrons by the magnetic field, which is proportional in magnitude to the magnetic field and to the electron velocity but perpendicular in direction to both the magnetic field and to their direction of motion.

Due to this force, the electrons which start to follow the applied voltage gradient quickly drift to one side of the conducting sheet until their mutual electrostatic repulsion there counterbalances the Lorentz force. At this point the electrons move straight along the applied voltage gradient, with the Lorentz force now exactly compensated by the Hall voltage due to the gradient in electron concentration.

For more details on the classical Hall effect see there; here we further just need the formulas for conductivity and resistivity:

Consider in the plane , with canonical coordinates and , the

With the current running in the -direction

the statement of the classical Hall effect is that

- not just the longitudinal field

but also

- the Hall field .

To say this more formally, recall that in a conductor the current is a linear function of the field with proportionality being the conductivity tensor , here a matrix, such that Ohm's law holds:

Assuming that the conducting sheet has no preferred direction, the conductivity tensor is of the form

for .

The corresponding resistivity tensor is the inverse matrix

in terms of which Ohm's law reads

In this tensorial language, the classical Hall effect is the statement that for transverse magnetic field the non-diagonal elements of the conductivity/resistivity tensors are non-vanishing, in that we have

In this case the basic matrix relation (1) is of some importance for understanding the measurement results in the integer quantum Hall effect below, since it implies the (maybe surprising-sounding) phenomenon that for non-vanishing Hall effect the longitudinal conductivity and resistivity may jointly vanish, see (4) below.

Concretely, the Hall resistivity turns out to be related to

-

– the number density of electrons per surface area,

-

– the magnetic field field strength,

-

– the electric charge of the electron,

by the formula

Integer quantum Hall effect

At extremely low temperature and extreme thin-ness of the conducting sheet, the above classical Hall effect exhibits modifications by quantum mechanical effects, due to the fact that the energy of electrons in a transverse magnetic field is quantized into discrete units known as Landau levels.

Since electrons are fermions, the Pauli exclusion principle demands that in their ground state the electrons fill the available Fermi sea with one electron per available state, below a given energy, the “chemical potential”. (Here, due to the strong external magnetic field, all electrons may be assumed to have their spin aligned along this field, so that the states in question concern just the remaining electron momenta.) The larger the magnetic field, the more quantum states are comprised by one Landau level.

In the case that the electrons fill exactly Landau levels – one speaks of filling fraction –, the next excited state, needed for the transport of charge, is separated by the energy gap to the next Landau level, and hence at an integer number of exactly filled Landau levels the Hall system behaves like an insulator with vanishing longitudinal conductivity .

What is measured in experiments is the longitudinal resistivity, which — by (1) with (2) — also goes to zero at these points of exactly filled Landau levels:

But the hallmark of the integer quantum Hall effect is that this vanishing of the longitudinal (conductivity and hence) resistivity is observed not just right when the magnetic field strength is at the critical value , but in a whole neighbourhood of these values:

Remarkably, the height of these Hall plateaus is an experimental constant to high precision, and is independent of the detailed nature of the underlying material, unaffected even by punching holes into the conducting sheet.

Yet more remarkably, the explanation for the horizontal extension of these plateaux is thought to be related to impurities in the material — in an ideally pure conductor the quantum Hall effect is expected to be invisible! The idea is that, due to the impurities, the idealized picture of Landau levels applies only to some of the electrons in the sample, while others are “localized” at/by the imporitites; and as the magnetic field is varied it is only after the reservoir of localized electrons has changed energy levels that it becomes the turn of the “quantum Hall electrons”.

To compute the Hall plateaux values:

The density of available states (number per surface area) available in a Landau level is

-

where is Planck's constant,

-

is the unit magnetic flux quantum,

hence there us room for one electron per magnetic flux quanta.

Therefore the th Landau level is exactly filled when

- there are exactly electrons per magnetic flux quanta

hence when

- the electron density is

which, according to (5), occurs theoretically right at (and in practice in a neighbourhood around) the critical magnetic field values

for which in turn, by (3), the Hall resistivity is

This is hence the height of the th Hall plateau in the integer quantum Hall effect.

These formulas, at least, generalize immediately from (positive) integers to (positive) rational numbers :

In particular, for the 1st Landau level to be filled up to an integer fraction , there must be exactly magnetic flux quanta per electron.

Nothing special is expected to happen at these fractional fillings of Landau level from the above understanding based all on the energy gap seen by non-interacting electrons (only) at the Fermi surface of a filled Landau level. But electron interaction changes this picture, leading to the fractional quantum Hall effect:

Fractional quantum Hall effect

Even though the integer quantum Hall effect (above) involves many electrons (a macroscopic number on the scale of the Avogadro constant), which necessarily interact strongly via their mutual Coulomb force, for understanding the effect it turns out (as indicated above) to be sufficient to consider the energy of single electrons right at the Fermi sea surface of a filled Landau level as if they were “free” (non-interacting). That such a radical (and conceptually unjustified!) approximation works so well is surprising on a fundamental level, but is entirely common in traditional solid state physics, notably in Landau's Fermi liquid theory.

However, yet closer experimental analysis at yet smaller temperatures shows that this approximation breaks down at some point, and that the strong interaction between the electrons makes them collectively behave in exotic ways.

Concretely, experiments show that Hall plateaus appear not just at integer filling levels, but (smaller) Hall plateaus appear also at certain rational filling fractions

Concretely, by the same computation as for (7), the fractional Hall plateaux are at

This experimentally observed phenomenon is thus called the fractional quantum Hall effect.

Unfortunately, due to the general open problem of formulating and analyzing non-perturbative quantum field theory, there is essentially no first-principles understanding of what causes the fractional quantum Hall effect!

What people have come up with, instead, are:

-

ad hoc (mental) models of how the electrons form supposedly “bound states” with magnetic flux quanta: “composite fermions”,

suggesting that the fractional quantum Hall effect is just the integer quantum Hall effect again, now not for plain electrons but for their exotic “fractional” quasi-particle/quasi-hole bound states,

-

some educated guesses as to the many-electron wavefunction describing the fractional Hall quantum state – Laughlin wavefunctions,

which, while just guessed, are confirmed well by experiment and have in practice become the effective theory for FQH systems,

-

some actual effectice quantum field theory description by variants of abelian Chern-Simons theory.

For more on Laughlin wavefunctions and on effective abelian Chern-Simons theory in the FQH context, see there.

Composite particle picture

The simple basic assumption of the “composite particle” (CP) heuristic for explaining the FQH effect is that:

One electron “bound to” (maybe better: “grouped with”) flux quanta behaves like

The idea behind this is, heuristically, that as such pairs of electron+flux compounds are moved around each other, the intrinsic particle statistics of the pairs of electrons (according to which the wavefunction picks up a factor of ) combines with the Aharonov Bohm phases of the electrons circling around the fluxes (according to which the wavefunction picks up another factor of ), to make for a total exchange phase of

hence for

-

a total phase if is odd, as for fermions,

-

a total phase if is even, as for bosons.

(Not so clear how to really justify this combination of particle statistics with Aharonov-Bohm phases, as these are not on the same footing, but it just seems to work as a heuristic model.)

If one accepts this heuristics of electron+flux composite particles, then it provides the following heuristic explanation of the fractional quantum Hall effect, in fact it provides two alternative explanations.

First, at unit filling fraction with odd, there are flux quanta per electron. Thinking of these as being coupled in the form of “composite bosons” (since is assumed to be odd, which are indeed the primary filling fractions seen in experiment, though far from the only ones) then the effective system is now bosonic and hence may condense to give the fractional quantum Hall phase (Girvin & MacDonald 1987 p 1254).

Further exposition of this perspective by Störmer 1999 is quoted below.

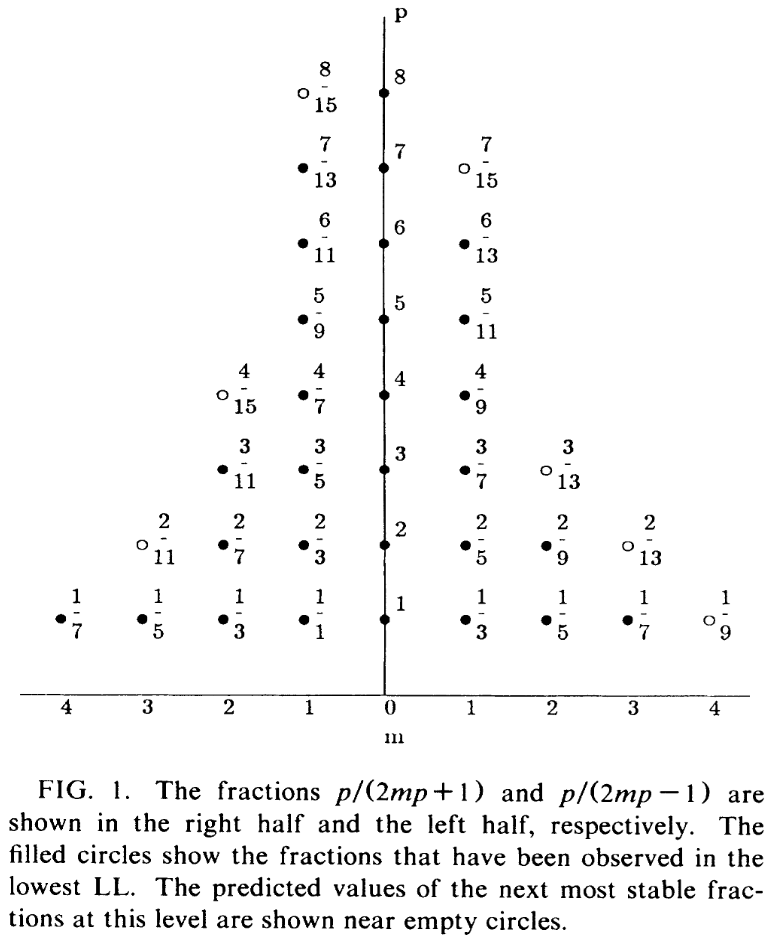

But Jain 1989, 1992, 2007 has argued that the following alternative perspective of composite fermions is more compelling and in any case more general and more expressive, as it neatly captures also the correct hierarchy of filling fractions with :

First assume that the electrons each bind to flux quanta () to make composite fermions, and then assume that these composite fermions themselves show an integer quantum Hall effect at filling number , hence that there are such composite fermions for each remaining (surplus, unbound) flux quantum.

In total then the ratio of flux quanta over electrons is

(the sign choice reflecting choice of relative orientation of the magnetic field) and so the corresponding filling fractions are (Jain 1989 p 1-2)

Remarkably, this Jain sequence formula captures a significant part of the zoo of observed filling fractions with odd denominators:

Further fractions have been argued to be explained this way if one assumes moreover that the composite fermions may themselves exhibit not just the integer also a fractional quantum Hall effect [Chang & Jain 2004]

A vivid account of the composite boson picture at odd unit fractions of electron-filling is given by Störmer 1999:

“In the FQHE, the electrons assume an even more favorable state [than in the IQHE], unforeseen by theory, by conducting an elaborate, mutual, quantum-mechanical dance. Many-particle effects are extraordinarily challenging to address theoretically. […] on occasion many-particle interactions become the essence of a physical effect. Superconductivity and superfluidity are of such intricate origin. To account for their occurrence one had to devise novel, sophisticated theoretical means. The emergence of the FQHE requires such a new kind of thinking. […]

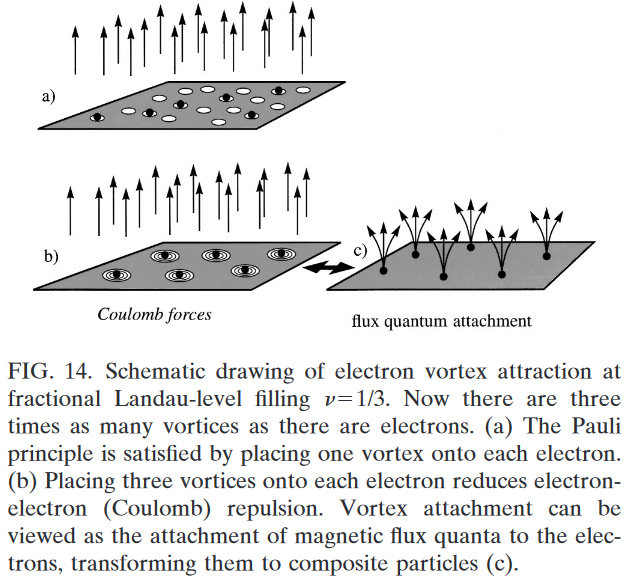

It was an important conceptual step to realize that an impinging magnetic field could be viewed as creating tiny whirlpools, so-called vortices, in this lake of charge—one for each flux quantum of the magnetic field. […] Casting electron-electron correlation in terms of vortex attachment facilitates the comprehension of this intricate many-particle behavior. Regarding the vortices as little whirlpools ultimately remains a crutch for visualizing something that has no classical analog. […]

At magnetic fields higher than the IQHE, the stronger magnetic field provides more flux quanta and hence there are more vortices than there are electrons. The Pauli principle is readily satisfied by placing one vortex onto each electron [Fig. 14(a)]—but there are more vortices available. The electron system can considerably reduce its electrostatic Coulomb energy by placing more vortices onto each electron [Fig. 14(b)]. More vortices on an electron generate a bigger surrounding whirlpool, pushing further away all fellow electrons, thereby reducing the repulsive energy. […]

Vortices are the expression of flux quanta in the 2D electron system, and each vortex can be thought of as having been created by a flux quantum. Conceptually, it is advantageous to represent the vortices simply by their “generators”, the flux quanta themselves. Then the placement of vortices onto electrons becomes equivalent to the attachment of magnetic flux quanta to the carriers. Electrons plus flux quanta can be viewed as new entities, which have come to be called composite particles, CPs.

As these objects move through the liquid, the flux quanta act as an invisible shield against other electrons. Replacing the system of highly interacting electrons by a system of electrons with such a “guard ring” – compliments of the magnetic field – removes most of the electron-electron interaction from the problem and leads to composite particles which are almost void of mutual interactions. It is a minor miracle that such a transformation from a very complex many-particle problem of well-known objects (electrons in a magnetic field) to a much simpler single-particle problem of rather complex objects (electrons plus flux quanta) exists and that it was discovered.

CPs act differently from bare electrons. All of the external magnetic field has been incorporated into the particles via flux quantum attachment to the electrons. Therefore, from the perspective of CPs, the magnetic field has disappeared and they no longer are subject to it. They inhabit an apparently field-free 2D plane. Yet more importantly, the attached flux quanta change the character of the particles from fermions to bosons and back to fermions. […]

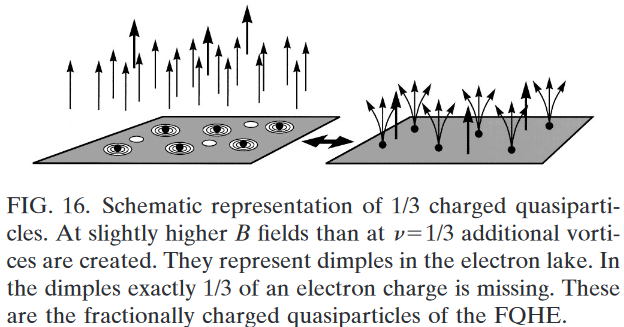

As the magnetic field deviates from exactly filling to higher fields, more vortices are being created (Fig. 16). They are not attached to any electrons, since this would disturb the symmetry of the condensed state. The amount of charge deficit in any of these vortices amounts to exactly 1/3 of an electronic charge. These quasiholes (whirlpool in the electron lake) are effectively positive charges as compared to the negatively charged electrons. An analogous argument can be made for magnetic fields slightly below and the creation of quasielectrons of negative charge . Quasiparticles can move freely through the 2D plane and transport electrical current. They are the famous 1/3 charged particles of the FQHE that have been observed by various experimental means […].

Plateau formation in the FQHE arises, in analogy to plateau formation in the IQHE from potential fluctuations and the resulting localization of carriers. In the case of the FQHE the carriers are not electrons, but, instead, the bizarre fractionally charged quasiparticles.

[end of excerpt from Störmer 1999]

Properties

Braiding phase

In an FQH system, when one quasi-hole (unpaired flux quantum) is adiabatically moved past another, hence one quasi-hole moved along half a circle centered at the other, then their joint quantum state picks up a Berry phase

in , exhibiting the quasi-holes as abelian anyons.

At unit fraction filling factors the angle of that braiding phase is the same fraction of (up to a sign reflecting the orientation of the braiding and the choice of quasi-holes over quasi-particles)

this according to a Berry phase computation via the quantum adiabatic theorem, due to Arovas, Schrieffer & Wilczek 1984 (12) (also claimed in Halperin 1984 p 1584).

It appears that Su 1986 (3) claims that (11) should hold for general filling fractions , but the commonly accepted statement nowadays is different:

Motivated by Halperin 1984, Goldhaber & Jain 1995 claim, reviewed by Jain 2007 (9.46) that for filling factors in the Jain sequence (10) the braiding angle is

Remark

While in the special case the formula (12) still differs from (11) it does so only by a unit shift

and hence by a sign of the corresponding braiding phase, which Jain 2007 (9.49) attributes but to a different convention of normalizing the corresponding Laughlin wavefunction.

For the two cases and , equation (12) appears to be confirmed first by numerical computations (referenced around Jain 2007 (9.46)) and then, starting around 2020, this braiding angle is reported to be observed in experiments for the cases (see Nakamura et al. 2020, Nakamura et al. 2023 p 1,7 and further references below).

Remark

More precisely, these interferometry experiments measure the effect of full rotations and hence twice the braiding angle modulo , thus being insensitive to the shift in (13). Concretely, these experiments at do not distinguish between braiding angles and .

Moreover, for the formula (12) happens to coincide with on the nose.

Remark

The hierarchical K-matrix formalism seems to allow more general relations between filling factor and braiding phase, cf. Wen 1995 (2.30-1).

As a topological insulator

The bulk/edge behaviour in a quantum Hall effect is that of a topological insulator. (While topological insulator materials typically show this behaviour without the need of a strong magnetic field.)

(…)

Related concepts

Types of Hall effects

See also:

References

General

Review:

-

Klaus von Klitzing, The quantized Hall effect, Rev. Mod. Phys. 58 519 (1986) [doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.58.519]

-

Richard E. Prange, Steven M. Girvin (eds.): The Quantum Hall Effect, Graduate Texts in Contemporary Physics, Springer (1986, 1990) [doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-3350-3]

-

Tapash Chakraborty, Pekka Pietiläinen: The Quantum Hall Effects – Integral and Fractional, Springer Series in Solid State Sciences (1995) [doi:10.1007/978-3-642-79319-6]

-

Daijiro Yoshioka: The Quantum Hall Effect, Springer (2002) [doi:10.1007/978-3-662-05016-3]

-

Benoît Douçot, Vincent Pasquier, Bertrand Duplantier, Vincent Rivasseau (eds.): The Quantum Hall Effect – Poincaré Seminar 2004, Progress in Mathematical Physics, Springer (2005) [doi:10.1007/3-7643-7393-8]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen: Theory of quantum Hall States, chapter 7 in: Quantum Field Theory of Many-Body Systems: From the Origin of Sound to an Origin of Light and Electrons, Oxford Academic (2007) [doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199227259.001.0001, pdf]

-

David Tong: The Quantum Hall Effect, lecture notes (2016) [arXiv:1606.06687, course webpage, pdf, pdf]

-

The quantum Hall effect [pdf]

-

Eduardo Fradkin, chapters 12, 13 in: Field Theories of Condensed Matter Physics, Cambridge University Press (2013) [doi:10.1017/CBO9781139015509, ISBN:9781139015509]

-

Eduardo C. Marino: Quantum Hall Effect, chapter 26 in: Quantum Field Theory Approach to Condensed Matter Physics, Cambridge University Press (2017) [doi:10.1017/9781139696548]

-

Daniel Arovas: Lecture Notes on Quantum Hall Effect (2024) [pdf]

Discussion via Newton-Cartan theory:

- William Wolf, James Read, Nicholas Teh, Edge modes and dressing fields for the Newton-Cartan quantum Hall effect [arXiv:2111.08052]

See also:

-

Wikipedia, Quantum Hall effect,

-

Wikipedia Fractional quantum Hall effect

Integral quantum Hall effect

Experiment

Original experimental detection:

-

Klaus von Klitzing, G. Dorda, M. Pepper: New Method for High-Accuracy Determination of the Fine-Structure Constant Based on Quantized Hall Resistance, Phys. Rev. Lett. 45 (1980) 494 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.494]

-

M. A. Paalanen, D. C. Tsui, A. C. Gossard: Quantized Hall effect at low temperatures, Phys. Rev. B 25 5566(R) (1982) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.25.5566]

Theory

While an intuitive understanding for the quantization of the Hall conductance has been given in

- Robert B. Laughlin, Quantized Hall conductivity in two dimensions, Phys. Rev. B 23 5632(R) (1981) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.23.5632]

a theoretical derivation of the effect was obtained only much later in

- Matthew Hastings, Spyridon Michalakis, Quantization of Hall conductance for interacting electrons without averaging assumptions, Commun. Math. Phys., 334:433–471, (2015) [arXiv:0911.4706, doi:10.1007/s00220-014-2167-x]

with closely related results in

- Alessandro Giuliani, Vieri Mastropietro, Marcello Porta, Universality of the Hall conductivity in interacting electron systems, Commun. Math. Phys. 349 (2017) 1107–1161 [arXiv:1511.04047, doi:10.1007/s00220-016-2714-8]

Review of this theory behind the quantum Hall effect:

-

Joseph E. Avron, Daniel Osadchy, Ruedi Seiler: A topological look at the quantum Hall effect, Physics Today 56 8 (2003) 38–42 [doi:10.1063/1.1611351]

-

Joseph E. Avron, Why is the Hall conductance quantized? (2017) [pdf, pdf]

-

Spyridon Michalakis, Why is the Hall conductance quantized?, Nature Reviews Physics 2 (2020) 392–393 [doi:10.1038/s42254-020-0212-6]

-

S. Klevtsov, X. Ma, G. Marinescu, P. Wiegmann, Quantum Hall effect and Quillen metric Commun. Math. Phys. 349 (2017) 819–855 [doi:10.1007/s00220-016-2789-2]

Fractional quantum Hall effect

General

Review and survey of the FQHE:

-

Horst L. Störmer: Pictures of the Fractional Quantized Hall Effect, in: Heterojunctions and Semiconductor Superlattices, Springer (1986) 50-63 [doi:10.1007/978-3-642-71010-0_4, pdf]

-

Horst L. Störmer: Nobel Lecture: The fractional quantum Hall effect, Rev. Mod. Phys. 71 (1999) 875 [doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.71.875]

-

Robert B. Laughlin: Nobel Lecture: Fractional quantization, Rev. Mod. Phys. 71 4 (1999) 863 [doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.71.863, pdf]

-

Steven M. Girvin: Introduction to the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect, Séminaire Poincaré 2 (2004) 53–74, reprinted in The Quantum Hall Effect, Progress in Mathematical Physics 45, Birkhäuser (2005) [pdf, doi:10.1007/3-7643-7393-8_4]

-

Peter Fulde, §14.2 in: Correlated Electrons in Quantum Matter, World Scientific (2012) [doi:10.1142/8419, pdf]

-

Thors H. Hansson, M. Hermanns, Steven H. Simon, S. F. Viefers: Quantum Hall Physics – hierarchies and CFT techniques, Rev. Mod. Phys. 89 (2017) 025005 [arXiv:1601.01697, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.89.025005]

-

Duncan Haldane: Geometry of flux attachment in the fractional quantum hall effect states, lecture at CESC Cargèse Corsica July 2017, abstract published in: Topological Phase Transitions And New Developments, World Scientific (2018) 2 [pdf, pdf, doi:10.1142/9789813271340_0002]

-

Bertrand I. Halperin, Jainendra K. Jain (eds.): Fractional Quantum Hall Effects – New Developments, World Scientific (2020) [doi:10.1142/11751]

-

Moty Heiblum, D. E. Feldman: Edge probes of topological order, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 35 18 (2020) 2030009 [arXiv:1910.07046, doi:10.1142/S0217751X20300094]

(also chapter 1 in Halperin & Jain 2020)

-

D. E. Feldman, Bertrand I. Halperin: Fractional charge and fractional statistics in the quantum Hall effects, Rep. Prog. Phys. 84 (2021) 076501 [doi:10.1088/1361-6633/ac03aa, arXiv:2102.08998]

-

Tudor D. Stanescu, Effective theory of Abelian fractional quantum Hall liquids, Section 6.2.1 of: Introduction to Topological Quantum Matter & Quantum Computation, CRC Press (2020) [ISBN:9780367574116]

-

Zlatko Papić, Ajit C. Balram: Fractional quantum Hall effect in semiconductor systems, Encyclopedia of Condensed Matter Physics 2nd ed 1 (2024) 285-307 [doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-90800-9.00007-X, arXiv:2205.03421]

See also:

- Wikipedia, Fractional Quantum Hall Effect

A quick review of the description via abelian Chern-Simons theory with further pointers is in the introduction of:

- Spencer D. Stirling, Abelian Chern-Simons theory with toral gauge group, modular tensor categories, and group categories, [arXiv:0807.2857]

On gapped boundary effects:

- Netanel H. Lindner, Erez Berg, Gil Refael, Ady Stern: Fractionalizing Majorana Fermions: Non-Abelian Statistics on the Edges of Abelian Quantum Hall States, Phys. Rev. X 2 (2012) 041002 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.2.041002, doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.2.041002, arXiv:1204.5733]

Realization via AdS/CFT in condensed matter physics:

- Mitsutoshi Fujita, Wei Li, Shinsei Ryu, Tadashi Takayanagi, Fractional Quantum Hall Effect via Holography: Chern-Simons, Edge States, and Hierarchy, JHEP 0906:066 (2009) [arXiv:0901.0924]

See also:

- Semyon Klevtsov, Dimitri Zvonkine: The Chern character of the Laughlin vector bundle in the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect [arXiv:2506.20363]

Specific filling fractions

On the FQH state:

-

Jainendra K. Jain: The enigma in a spin?, Physics 3 (2010) 71 [doi:10.1103/Physics.3.71, pdf]

-

Michael R Peterson: The fractional quantum Hall effect at filling factor : numerically searching for non-abelian anyons, J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 402 (2012) 012021 [doi:10.1088/1742-6596/402/1/012021]

-

R L Willett: The quantum Hall effect at filling factor, Rep. Prog. Phys. 76 (2013) 076501 [doi:10.1088/0034-4885/76/7/076501]

-

Ken K. W. Ma, Michael R. Peterson, V. W. Scarola, Kun Yang: Fractional quantum Hall effect at the filling factor , Encyclopedia of Condensed Matter 2nd ed. 1 (2024) 324-365 [arXiv:2208.07908, doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-90800-9.00135-9]

Observations of the FQH state:

-

D. R. Luhman, W. Pan, D.C. Tsui, L.N. Pfeiffer, K.W. Baldwin, K.W. West: Observation of a Fractional Quantum Hall State at in a Wide Quantum Well, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101 (2008) 266804 [arXiv:0810.2274, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.266804]

-

A. A. Zibrov, et al.: Even-denominator fractional quantum Hall states at an isospin transition in monolayer graphene, Nature Physics 14 (2018) 930–935 [doi;10.1038/s41567-018-0190-0]

Edge modes

On edge modes in fractional quantum Hall systems:

Original articles:

-

Xiao-Gang Wen: Chiral Luttinger liquid and the edge excitations in the fractional quantum Hall states, Phys. Rev. B 41 (1990) 12838 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.41.12838]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen: Topological order in rigid states and edge excitations in fractional quantum Hall states, Advances in Physics 44 5 (1995) 405-437 [arXiv:cond-mat/9506066, doi;10.1080/00018739500101566]

-

C. de C. Chamon, D. E. Freed, S. A. Kivelson, S. L. Sondhi, Xiao-Gang Wen: Two point-contact interferometer for quantum Hall systems, Phys. Rev. B 55 (1997) 2331 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.55.2331]

Review:

-

A. M. Chang: Chiral Luttinger liquids at the fractional quantum Hall edge, Rev. Mod. Phys. 75 (2003) 1449 [doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.75.1449]

-

David Tong: Edge Modes, chapter 6 of: Tong 2016

Experiment

Observation of the FQHE in :

- D. C. Tsui, Horst L. Stormer, A. C. Gossard: Two-Dimensional Magnetotransport in the Extreme Quantum Limit, Phys. Rev. Lett. 48 (1982) 1559 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.48.1559]

in graphene:

-

Xu Du, Ivan Skachko, Fabian Duerr, Adina Luican, Eva Y. Andrei: Fractional quantum Hall effect and insulating phase of Dirac electrons in graphene, Nature 462 192 (2009) [doi:10.1038/nature08522, arXiv:0910.2532]

-

Kirill I. Bolotin, Fereshte Ghahari, Michael D. Shulman, Horst L. Stormer, Philip Kim: Observation of the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect in Graphene, Nature 462 (2009) 196–199 [doi:10.1038/nature08582, arXiv:0910.2763]

in oxide interfaces:

- A. Tsukazaki et al.: Observation of the fractional quantum Hall effect in an oxide, Nature Materials 9 (2010) 889–893 [doi:10.1038/nmat2874]

in :

- B. A. Piot, J. Kunc, M. Potemski, D. K. Maude, C. Betthausen, A. Vogl, D. Weiss, G. Karczewski, T. Wojtowicz: Fractional quantum Hall effect in , PhysRev B. 82 (2010) 081307 (R) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.82.081307, arXiv:1006.0908]

Phenomenological models

Phenomenological models for the fractional quantum Hall effect:

The original Laughlin wavefunction:

- Robert B. Laughlin, Anomalous Quantum Hall Effect: An Incompressible Quantum Fluid with Fractionally Charged Excitations, Phys. Rev. Lett. 50 (1983) 1395 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.50.1395]

The Halperin multi-component model:

- Bertrand I. Halperin: Theory of the Quantized Hall Conductance, Helvetica Physica Acta 56 (1983) 75-102 [doi:10.5169/seals-115362, pdf]

The Haldane-Halperin hierachy model for FQH system at non-unit filling fractions:

-

F. Duncan M. Haldane: Fractional Quantization of the Hall Effect: A Hierarchy of Incompressible Quantum Fluid States, Phys. Rev. Lett. 51 (1983) 605 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.51.605]

-

Bertrand Halperin: Statistics of Quasiparticles and the Hierarchy of Fractional Quantized Hall States, Phys. Rev. Lett. 52 (1984) 1583 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.52.1583]

The composite-fermion model (CF) which explains the FQHE as the integer quantum Hall effect not of the bare electrons but of quasi-particles which they form (for reasons not explained by the model):

-

Jainendra K. Jain: Composite-fermion approach for the fractional quantum Hall effect, Phys. Rev. Lett. 63 (1989) 199 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.63.199]

-

Jainendra K. Jain: Microscopic theory of the fractional quantum Hall effect, Adv. Phys. 41 (1992) 105-146 [doi:10.1080/00018739200101483]

-

Jainendra K. Jain: Composite Fermions, Cambridge University Press (2007) [doi:10.1017/CBO9780511607561, §5:pdf, §9:pdf, §12:pdf]

On FQH of composite fermions:

- C.-C Chang, Jainendra K. Jain: Microscopic origin of the next generation fractional quantum Hall effect, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92 (2004) 196806 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.196806, arXiv:cond-mat/0404079]

Review:

- Jainendra K. Jain: Thirty Years of Composite Fermions and Beyond, chapter 1 in Halperin & Jain 2020, Fractional Quantum Hall Effects – New Developments, World Scientific (2020) [arXiv:2011.13488, doi:10.1142/11751]

Further discussion:

- Jainendra K. Jain: A note contrasting two microscopic theories of the fractional quantum Hall effect, Indian J of Phys 88 (2014) 915-929 [doi:10.1007/s12648-014-0491-9, arXiv:1403.5415]

Discussion highlighting the lack of microscopic explanation of these phenomenological models:

- Janusz E. Jacak: Topological approach to electron correlations at fractional quantum Hall effect, Annals of Physics 430 (2021) 168493 [doi:10.1016/j.aop.2021.168493]

[p 3:] “Though the Laughlin function very well approximates the true ground state at , the physical mechanism of related correlations and of the whole hierarchy of the FQHE remained, however, still obscure.”

“The so-called HH (Halperin–Haldane) model of consecutive generations of Laughlin states of anyonic quasiparticle excitations from the preceding Laughlin state has been abandoned early because of the rapid growth of the daughter quasiparticle size, which quickly exceeded the sample size.”

“the Halperin multicomponent theory and of the CF model advanced the understanding of correlations in FQHE, however, on a phenomenological level only. CFs were assumed to be hypothetical quasi-particles consisting of electrons and flux quanta of an auxiliary fictitious magnetic field pinned to them. The origin of this field and the manner of attachment of its flux quanta to electrons have been neither explained nor discussed.”

Introducing abelian Chern-Simons theory to the picture:

-

Ana Lopez, Eduardo Fradkin: Fractional quantum Hall effect and Chern-Simons gauge theories, Phys. Rev. B 44 (1991) 5246 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.44.5246]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen, Anthony Zee: Classification of Abelian quantum Hall states and matrix formulation of topological fluids, Phys. Rev. B 46 (1992) 2290 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.46.2290]

Abelian Chern-Simons for fractional quantum Hall effect

The idea of abelian Chern-Simons theory as an effective field theory exhibiting the fractional quantum Hall effect (abelian topological order) goes back to

-

Steven M. Girvin, around (10.7.15) in: Summary, Omissions and Unanswered Questions, Chapter 10 of: The Quantum Hall Effect, Graduate Texts in Contemporary Physics, Springer (1986, 1990) [doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-3350-3]

-

Steven M. Girvin, Allan H. MacDonald, around (10) of: Off-diagonal long-range order, oblique confinement, and the fractional quantum Hall effect, Phys. Rev. Lett. 58 12 (1987) (1987) 1252-1255 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.1252]

-

Shou Cheng Zhang, T. H. Hansson S. Kivelson: Effective-Field-Theory Model for the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect, Phys. Rev. Lett. 62 (1989) 82 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.62.82]

and was made more explicit in:

-

Xiao-Gang Wen, Anthony Zee: Quantum statistics and superconductivity in two spatial dimensions, Nuclear Physics B – Proceedings Supplements 15 (1990) 135-156 [doi:10.1016/0920-5632(90)90014-L]

-

B. Blok, Xiao-Gang Wen: Effective theories of the fractional quantum Hall effect at generic filling fractions, Phys. Rev. B 42 (1990) 8133 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.42.8133]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen: Topological Orders in Rigid States, Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 4 239 (1990) [doi:10.1142/S0217979290000139]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen, Qian Niu: Ground state degeneracy of the FQH states in presence of random potential and on high genus Riemann surfaces, Phys. Rev. B 41 9377 (1990) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.41.9377]

-

Jürg Fröhlich, T. Kerler: Universality in quantum Hall systems, Nuclear Physics B 354 2–3 (1991) 369-417 [doi:10.1016/0550-3213(91)90360-A]

-

Jürg Fröhlich, Anthony Zee: Large scale physics of the quantum hall fluid, Nuclear Physics B 364 3 (1991) 517-540 [doi:10.1016/0550-3213(91)90275-3]

-

Z. F. Ezawa, A. Iwazaki: Chern-Simons gauge theories for the fractional-quantum-Hall-effect hierarchy and anyon superconductivity, Phys. Rev. B 43 (1991) 2637 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.43.2637]

-

A. P. Balachandran, A. M. Srivastava: Chern-Simons Dynamics and the Quantum Hall Effect [arXiv:hep-th/9111006, spire:319826]

-

Ana Lopez, Eduardo Fradkin: Fractional quantum Hall effect and Chern-Simons gauge theories, Phys. Rev. B 44 (1991) 5246 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.44.5246, pdf]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen, Anthony Zee: Topological structures, universality classes, and statistics screening in the anyon superfluid, Phys. Rev. B 44 (1991) 274 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.44.274]

-

Roberto Iengo, Kurt Lechner: Anyon quantum mechanics and Chern-Simons theory, Physics Reports 213 4 (1992) 179-269 [doi:10.1016/0370-1573(92)90039-3]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen, Anthony Zee: Classification of Abelian quantum Hall states and matrix formulation of topological fluids, Phys. Rev. B 46 (1992) 2290 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.46.2290]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen, Anthony Zee: Shift and spin vector: New topological quantum numbers for the Hall fluids, Phys. Rev. Lett. 69 (1992) 953, Erratum Phys. Rev. Lett. 69 3000 (1992) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.953]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen: Theory of Edge States in Fractional Quantum Hall Effects, International Journal of Modern Physics B 06 10 (1992) 1711-1762 [doi:10.1142/S0217979292000840]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen, Topological orders and Edge excitations in FQH states, Advances in Physics 44 (1995) 405 [doi:10.1080/00018739500101566, arXiv:cond-mat/9506066]

(in the context of topological order)

-

A. P. Balachandran, L. Chandar, B. Sathiapalan: Chern-Simons Duality and the Quantum Hall Effect, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A11 (1996) 3587-3608 [doi:10.1142/S0217751X96001693, arXiv:hep-th/9509019]

Early review:

-

Shou Cheng Zhang: The Chern-Simons-Landau-Ginzburg theory of the fractional quantum Hall effect, International Journal of Modern Physics B 06 01 (1992) 25-58 [doi:10.1142/S0217979292000037, pdf]

-

Anthony Zee: Quantum Hall Fluids, in: Field Theory, Topology and Condensed Matter Physics, Lecture Notes in Physics 456, Springer (1995) [doi:10.1007/BFb0113369, arXiv:cond-mat/9501022]

-

Xiao-Gang Wen: Topological orders and Edge excitations in FQH states, Advances in Physics 44 5 (1995) 405 [doi:10.1080/00018739500101566, arXiv:cond-mat/9506066]

Further review and exposition:

-

Xiao-Gang Wen: Effective theory of fractional quantum Hall liquids, section 7.3 of: Quantum Field Theory of Many-Body Systems: From the Origin of Sound to an Origin of Light and Electrons, Oxford Academic (2007)[doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199227259.001.0001, pdf]

-

Yuan-Ming Lu, Ashvin Vishwanath, part II of: Theory and classification of interacting integer topological phases in two dimensions: A Chern-Simons approach, Phys. Rev. B 86 (2012) 125119, Erratum Phys. Rev. B 89 (2014) 199903 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.86.125119, arXiv:1205.3156]

-

Eduardo Fradkin, chapter 13.7 of: Field Theories of Condensed Matter Physics, Cambridge University Press (2013) [doi:10.1017/CBO9781139015509, ISBN:9781139015509]

-

Edward Witten, pp 30 in: Three Lectures On Topological Phases Of Matter, La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento 39 (2016) 313-370 [doi:10.1393/ncr/i2016-10125-3, arXiv:1510.07698]

-

David Tong §5 of: The Quantum Hall Effect, lecture notes (2016) [arXiv:1606.06687, course webpage, pdf, pdf]

-

Josef Wilsher: The Chern–Simons Action & Quantum Hall Effect: Effective Theory, Anomalies, and Dualities of a Topological Quantum Fluid, PhD thesis, Imperial College London (2020) [pdf]

For discussion of the fractional quantum Hall effect via abelian but noncommutative (matrix model-)Chern-Simons theory

- see there.

More on edge modes:

- Michael Levin: Protected edge modes without symmetry, Phys. Rev. X 3 021009 (2013) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.3.021009, arXiv:1301.7355]

The symmetry protected situation:

- Yuan-Ming Lu, Ashvin Vishwanath: Classification and properties of symmetry-enriched topological phases: Chern-Simons approach with applications to spin liquids, Phys. Rev. B 93 (2016) 155121 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.93.155121, arXiv:1302.2634]

Amplification of the K-matrix formalism as being about (not the usual single-component but) multi-component FQH systems:

-

Maissam Barkeshli, Xiao-Gang Wen: Bilayer quantum Hall phase transitions and the orbifold non-Abelian fractional quantum Hall states, Phys. Rev. B 95 (2017) 085135 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.95.085135, arXiv:1010.4270]

-

Inti Sodemann, Itamar Kimchi, Chong Wang, T. Senthil: Composite fermion duality for half-filled multicomponent Landau levels, Phys. Rev. B 95 (2017) 085135 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.95.085135, doi:1609.08616]

-

Tian-Sheng Zeng: Fractional quantum Hall effect of Bose-Fermi mixtures, Phys. Rev. B 103 (2021) L201118 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.103.L201118, arXiv:2012.08203]

-

Liangdong Hu, Zhao Liu, W. Zhu: Modular transformation and anyonic statistics of multi-component fractional quantum Hall states, Phys. Rev. B 108 (2023) 235121 [arXiv:2301.06427, doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.108.235121]

-

Tian-Sheng Zeng: Three-component fractional quantum Hall effect in topological flat bands, Phys. Rev. B 110 (2024) 165126 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.110.165126, arXiv:2407.08568]

Further developments:

-

Dmitriy Belov, Gregory W. Moore, §7 of: Classification of abelian spin Chern-Simons theories [arXiv:hep-th/0505235]

-

Christian Fräßdorf: Abelian Chern-Simons Theory for the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect in Graphene, Phys. Rev. B 97 115123 (2018) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.97.115123, arXiv:1712.03595]

-

Kristan Jensen, Amir Raz: The Fractional Hall hierarchy from duality [arXiv:2412.17761]

-

Abhishek Agarwal, Dimitra Karabali, V. Parameswaran Nair: Fractional quantum Hall effect in higher dimensions, Phys. Rev. D 111 (2025) 025002 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.111.025002, arXiv:2410.14036]

Quantum Hall effect via non-commutative geometry

Discussion of the integer quantum Hall effect via a Brillouin torus with noncommutative geometry and using the Connes-Chern character:

- Jean Bellissard, A. van Elst, H. Schulz-Baldes: The noncommutative geometry of the quantum Hall effect, J. Math. Phys. 35 5373 (1994) [doi:10.1063/1.530758, cond-mat/9411052]

Generalization of BvESB94 to the fractional quantum Hall effect:

- Matilde Marcolli, Varghese Mathai: Towards the fractional quantum Hall effect: a noncommutative geometry perspective, in Noncommutative Geometry and Number Theory, Vieweg (2006) [doi:10.1007/978-3-8348-0352-8_12, arXiv:cond-mat/0502356]

See also exposition in:

- Vincent Pasquier: Quantum Hall Effect and Non-commutative Geometry, in: Quantum Spaces, Progress in Mathematical Physics 53, Birkhäuser (2007) [doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-8522-4_1, pdf]

Discussion of the fractional quantum Hall effect via abelian but noncommutative (matrix model-)Chern-Simons theory:

-

Leonard Susskind: The Quantum Hall Fluid and Non-Commutative Chern Simons Theory [arXiv:hep-th/0101029]

-

Simeon Hellerman, Leonard Susskind: Realizing the Quantum Hall System in String Theory [arXiv:hep-th/0107200]

(relating this to M5-branes via the BFSS matrix model)

-

Alexios P. Polychronakos: Quantum Hall states as matrix Chern-Simons theory, JHEP 0104:011 (2001) [doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2001/04/011, arXiv:hep-th/0103013]

-

Simeon Hellerman, Mark Van Raamsdonk: Quantum Hall Physics = Noncommutative Field Theory, JHEP 0110:039 (2001) [doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2001/10/039, arXiv:hep-th/0103179]

-

Eduardo Fradkin, Vishnu Jejjala, Robert G. Leigh: Non-commutative Chern-Simons for the Quantum Hall System and Duality, Nucl. Phys. B 642 (2002) 483-500 [doi:10.1016/S0550-3213(02)00616-8, arXiv:cond-mat/0205653]

-

Andrea Cappelli, Ivan D. Rodriguez: Matrix Effective Theories of the Fractional Quantum Hall effect, J. Phys. A 42 (2009) 304006 [doi:10.1088/1751-8113/42/30/304006, arXiv:0902.0765]

-

Zhihuan Dong, T. Senthil: Non-commutative field theory and composite Fermi Liquids in some quantum Hall systems, Phys. Rev. B 102 (2020) 205126 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.102.205126, arXiv:2006.01282]

Anyons in fractional quantum Hall systems

References on anyon-excitations (satisfying braid group statistics) in the quantum Hall effect (for more on the application to topological quantum computation see the references there):

The prediction of abelian anyon-excitations in the quantum Hall effect (i.e. satisfying braid group statistics in 1-dimensional linear representations of the braid group) by computation of Berry phases of Laughlin wavefunctions via the quantum adiabatic theorem:

-

Bertrand I. Halperin: Statistics of Quasiparticles and the Hierarchy of Fractional Quantized Hall States, Phys. Rev. Lett. 52 (1984) 1583 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.52.1583]

Erratum, Phys. Rev. Lett. 52 (1984) 2390 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.52.2390.4]

-

Daniel P. Arovas, John Robert Schrieffer, Frank Wilczek, Fractional Statistics and the Quantum Hall Effect, Phys. Rev. Lett. 53 (1984) 722 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.722]

(for filling fraction )

-

W. P. Su: Statistics of the fractionally charged excitations in the quantum Hall effect, Phys. Rev. B 34 (1986) 1031 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.34.1031]

(claim for general filling fraction )

-

A. S. Goldhaber, Jainendra K. Jain: Characterization of fractional-quantum-Hall-effect quasiparticles, Physics Letters A 199 3–4 (1995) 267-273 [doi:10.1016/0375-9601(95)00101-8, arXiv:cond-mat/9501080]

(for Jain series fractions )

-

(review)

The original discussion of non-abelian anyon-excitations in the quantum Hall effect (i.e. satisfying braid group statistics in higher dimensional linear representations of the braid group, related to modular tensor categories):

- Gregory Moore, Nicholas Read, Nonabelions in the fractional quantum Hall effect, Nucl. Phys. 360B(1991)362 (pdf, doi:10.1016/0550-3213(91)90407-O)

Review:

-

Ady Stern, Anyons and the quantum Hall effect – A pedagogical review, Annals of Physics 323 1 (2008) 204-249 [doi:10.1016/j.aop.2007.10.008, arXiv:0711.4697]

-

Menelaos Zikidis: Abelian Anyons and Fractional Quantum Hall Effect, Seminar notes (2017) [pdf, pdf]

-

Ady Stern: Engineering Non-Abelian Quasi-Particles in Fractional Quantum Hall States – A Pedagogical Introduction, Ch. 9 in: Fractional Quantum Hall Effects, World Scientific (2020) 435-486 [doi:10.1142/9789811217494_0009]

-

D. E. Feldman, Bertrand Halperin: Fractional charge and fractional statistics in the quantum Hall effects, Rep. Prog. Phys. 84 (2021) 076501 [doi:10.1088/1361-6633/ac03aa, arXiv:2102.08998]

On (anyons in) fractional quantum Hall systems as potential quantum hardware for topological quantum computing:

-

D. V. Averin, V. J. Goldman: Quantum computation with quasiparticles of the fractional quantum Hall effect, Solid State Communications 121 1 (2001) 25-28 [doi:10.1016/S0038-1098(01)00447-1, arXiv:cond-mat/0110193]

-

Sankar Das Sarma, Michael Freedman, Chetan Nayak: Topologically-Protected Qubits from a Possible Non-Abelian Fractional Quantum Hall State, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94 166802 (2005) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.166802, arXiv:cond-mat/0412343]

-

Sergey Bravyi: Universal Quantum Computation with the Fractional Quantum Hall State, Phys. Rev. A 73 042313 (2006) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.73.042313, arXiv:quant-ph/0511178]

-

Maissam Barkeshli, Xiao-Liang Qi: Synthetic Topological Qubits in Conventional Bilayer Quantum Hall Systems, Phys. Rev. X 4 (2014) 041035 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.4.041035, arXiv:1302.2673]

-

Roger S. K. Mong et al.: Universal Topological Quantum Computation from a Superconductor-Abelian Quantum Hall Heterostructure, Phys. Rev. X 4 (2014) 011036 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.4.011036, arXiv:1307.4403]

Observation of anyons in fractional quantum Hall systems

While the occurrence of anyon-excitations in the fractional quantum Hall effect is a robust theoretical prediction (see the references above), and while the fractional quantum Hall effect itself has long been established in experiment, the actual observation of anyons in these systems is subtle.

An early claim of the observation of non-abelian anyons seems to remain unconfirmed:

- Sanghun An, P. Jiang, H. Choi, W. Kang, S. H. Simon, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. West, K. W. Baldwin, Braiding of Abelian and Non-Abelian Anyons in the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect [arXiv:1112.3400]

Observation in gallium arsenide () semiconductor heterostructures:

-

H. Bartolomei, et al.: Fractional statistics in anyon collisions, Science 368 6487 (2020) 173-177 [doi:10.1126/science.aaz5601, arXiv:2006.13157]

-

James Nakamura et al.: Aharonov–Bohm interference of fractional quantum Hall edge modes, Nature Physics 15 563–569 (2019) [doi:10.1038/s41567-019-0441-8, arXiv:1901.08452]

-

James Nakamura et al.: Direct observation of anyonic braiding statistics, Nat. Phys. 16 (2020) 931–936 [doi:10.1038/s41567-020-1019-1, arXiv:2006.14115]

-

Bob Yirka, Best evidence yet for existence of anyons, PhysOrg News (July 10, 2020) [phys.org/news/2020-07]

-

Davide Castelvecchi: Welcome anyons! Physicists find best evidence yet for long-sought 2D structures, Nature News, 583 (03 July 2020) 176-177 [doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01988-0]

-

James Nakamura et al.: Impact of bulk-edge coupling on observation of anyonic braiding statistics in quantum Hall interferometers, Nature Communications 13 344 (2022) [doi:10.1038/s41467-022-27958-w, arXiv:2107.02136]

-

James Nakamura et al.: Fabry-Perot interferometry at the fractional quantum Hall state, Phys. Rev. X 13 (2023) 041012 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.13.041012, arXiv:2304.12415]

-

M. Ruelle et al.: Comparing fractional quantum Hall Laughlin and Jain topological orders with the anyon collider, Physical Review X 13 (2023) 011031 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.13.011031, arXiv:2210.01066]

-

Pierre Glidic et al: Cross-Correlation Investigation of Anyon Statistics in the and Fractional Quantum Hall States, Phys. Rev. X 13 011030 (2023) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.13.011030, arXiv:2210.01054]

-

Pierre Glidic et al.: Signature of anyonic statistics in the integer quantum Hall regime, Nature Commun. 15 6578 (2024) 1 [doi:10.1038/s41467-024-50820-0, arXiv:2401.06069]

-

Hemanta Kumar Kundu et al.: Anyonic interference and braiding phase in a Mach-Zehnder interferometer, Nature Physics 19 (2023) 515–521 [doi:10.1038/s41567-022-01899-z, arXiv:2203.0420]

-

A. Veillon et al.: Observation of the scaling dimension of fractional quantum Hall anyons, Nature 632 (2024) 517–521 [doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07727-z]

-

Bikash Ghosh, Maria Labendik, Liliia Musina, Vladimir Umansky, Moty Heiblum, David F. Mross: Anyonic Braiding in a Chiral Mach-Zehnder Interferometer, Nature Physics (2025) [doi:10.1038/s41567-025-02960-3, arXiv:2410.16488]

and in graphene heterostructures:

-

Noah Samuelson et al.: Anyonic statistics and slow quasiparticle dynamics in a graphene fractional quantum Hall interferometer [arXiv:2403.19628]

-

Jehyun Kim et al.: Aharonov-Bohm Interference in Even-Denominator Fractional Quantum Hall States [arXiv:2412.19886]

See also:

- Flavio Ronetti et al.: Probing anyon statistics on a single-edge loop in the fractional quantum Hall regime [arXiv:2506.09774]

On appatent bound states of FQH anyons:

- Mytraya Gattu, Jainendra K. Jain: Molecular anyons in fractional quantum Hall effect [arXiv:2505.22782]

Superconducting defect anyons in FQH systems

On non-abelian (parafermionic Majorana zero mode) defect anyons associated with superconducting islands inside abelian fractional quantum Hall systems:

-

Netanel H. Lindner, Erez Berg, Gil Refael, Ady Stern: Fractionalizing Majorana fermions: non-abelian statistics on the edges of abelian quantum Hall states, Phys. Rev. X 2 (2012) 041002 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.2.041002arXiv:1204.5733]

-

David J. Clarke, Jason Alicea, Kirill Shtengel: Exotic non-Abelian anyons from conventional fractional quantum Hall states, Nature Communications 4 1348 (2013) [ncomms:2340, arXiv:1204.5479]

-

Abolhassan Vaezi: Fractional topological superconductor with fractionalized Majorana fermions, Phys. Rev. B 87 (2013) 035132 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.87.035132, arXiv:1204.6245]

-

Roger S. K. Mong, David J. Clarke, Jason Alicea, Netanel H. Lindner, Paul Fendley, Chetan Nayak, Yuval Oreg, Ady Stern, Erez Berg, Kirill Shtengel, Matthew P. A. Fisher: Universal Topological Quantum Computation from a Superconductor-Abelian Quantum Hall Heterostructure, Phys. Rev. X 4 (2014) 011036 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.4.011036, arXiv:1307.4403]

-

Younghyun Kim, David J. Clarke, Roman M. Lutchyn: Coulomb Blockade in Fractional Topological Superconductors, Phys. Rev. B 96 (2017) 041123 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.96.041123, arXiv:1703.00498]

-

Luiz H. Santos, Taylor L. Hughes: Parafermionic Wires at the Interface of Chiral Topological States, Phys. Rev. Lett. 118 (2019) 136801 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.136801]

-

Luiz H. Santos: Parafermions in Hierarchical Fractional Quantum Hall States, Phys. Rev. Research 2 (2020) 013232 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.013232, arXiv:1906.07188]

Supersymmetry in fractional quantum Hall systems

On hidden/emergent supersymmetry in fractional quantum Hall systems (cf. SuSy between Laughlin and Moore-Read states):

(for a similar phenomenon cf. also hadron supersymmetry)

The use of supergeometry in the description of fractional quantum Hall systems, and the observation that the Moore-Read state is the top super field-component of a super-Laughlin wavefunction (see there) was promoted in:

-

Kazuki Hasebe: Supersymmetric Quantum-Hall Effect on a Fuzzy Supersphere, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94 (2005) 206802 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.206802]

-

Kazuki Hasebe: Quantum Hall liquid on a noncommutative superplane, Phys. Rev. D 72 (2005) 105017 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.72.105017]

-

Kazuki Hasebe: Quantum Hall Effect Based on SUSY Non-Commutative Geometry, Progress of Theoretical Physics Supplement 171 (2007) 154–159 [doi:10.1143/PTPS.171.154]

-

Kazuki Hasebe: Unification of Laughlin and Moore–Read states in SUSY quantum Hall effect, Physics Letters A 372 9 (2008) 1516-1520 [doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2007.09.071]

-

Kazuki Hasebe: Supersymmetric Quantum Hall Liquid with a Deformed Supersymmetry, Phys. Atom. Nucl. 73 (2010) 345-351 [arXiv:0901.1724, doi:10.1134/S1063778810020225]

-

Kazuki Hasebe: Supersymmetric Quantum Spin Model and Quantum Hall Effect, Soryushiron Kenkyu Electronics 117 6 (2010) F59- [doi:10.24532/soken.117.6_F59, spire:1687527]

Based on this, the proposal that also the “magentoroton” and the “neutral fermion” excitations of the Moore&Read-state should be superpartners of each other, is due to:

- Andrey Gromov, Emil J. Martinec, Shinsei Ryu: Collective excitations at filling factor : The view from superspace, Phys. Rev. Lett. 125 (2020) 077601 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.077601, arXiv:1909.06384]

(via superspace formulation)

further discussed in:

-

Ken K. W. Ma, Ruojun Wang, Kun Yang: Realization of Supersymmetry and Its Spontaneous Breaking in Quantum Hall Edges, Phys. Rev. Lett. 126 (2021) 206801 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.206801, arXiv:2101.05448]

-

Patricio Salgado-Rebolledo, Giandomenico Palumbo: Nonrelativistic supergeometry in the Moore-Read fractional quantum Hall state, Phys. Rev. D 106 (2022) 065020 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.106.065020, arXiv:2112.14339]

-

Songyang Pu, Ajit C. Balram, Mikael Fremling, Andrey Gromov, Zlatko Papić: Signatures of Supersymmetry in the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect, Phys. Rev. Lett. 130 (2023) 176501 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.130.176501, arXiv:2301.04169]

“Our results suggest that the SUSY structure is intrinsically present in spectral properties of the state”

-

Dung Xuan Nguyen, Kartik Prabhu, Ajit C. Balram, Andrey Gromov: Supergravity model of the Haldane-Rezayi fractional quantum Hall state, Phys. Rev. B 107 (2023) 125119 [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.107.125119, arXiv:2212.00686]

(proposal for a supergravity formulation)

-

Yang Liu, Tongzhou Zhao, T. Xiang: Resolving Geometric Excitations of Fractional Quantum Hall States, Phys. Rev. B 110 195137 (2024) [arXiv:2406.11195, doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.110.195137]

“Our findings support the hypothesis of emergent supersymmetry and highlight the potential for detecting neutral fermions in future experiments.”

See also:

-

Christopher Ting, C. H. Lai: Spinning Braid Group Representation and the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect, Nucl. Phys. B 396 (1993) 429-464 [doi:10.1016/0550-3213(93)90659-D, arXiv:hep-th/9202024]

-

Brian P Dolan: Supersymmetric Yang-Mills and the Quantum Hall Effect, International Journal of Modern Physics A 21 23/24 (2006) 4807-4822 [arXiv:hep-th/0505138, doi:10.1142/S0217751X06033891, pdf]

-

Eran Sagi, Raul A. Santos: Supersymmetry in the Fractional Quantum Hall Regime, Phys. Rev. B 95 205144 (2017) [doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.95.205144, arXiv:1610.07627]

-

Jin-Beom Bae, Sungjay Lee, section 5 of: Emergent Supersymmetry on the Edges, SciPost Phys. 11 091 (2021) [doi:10.21468/SciPostPhys.11.5.091, arXiv:2105.02148]

In string/M-theory

On geometric engineering of aspects of the quantum Hall effect on M5-brane worldvolumes via an effective noncommutative geometry induced by a constant B-field flux density:

- Simeon Hellerman, Leonard Susskind: Realizing the Quantum Hall System in String Theory [arXiv:hep-th/0107200]

Alternative derivation via flux quantization on probe M5-branes according to Hypothesis H:

-

Hisham Sati, Urs Schreiber: Abelian Anyons on Flux-Quantized M5-Branes [arXiv:2408.11896]

-

Hisham Sati, Urs Schreiber: Engineering of Anyons on M5-Probes [arXiv:2501.17927]

-

Hisham Sati, Urs Schreiber: Fractional Quantum Hall Anyons via the Algebraic Topology of exotic Flux Quanta [arXiv:2505.22144]

Last revised on July 7, 2025 at 18:11:05. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.