nLab Introduction to Topology -- 1

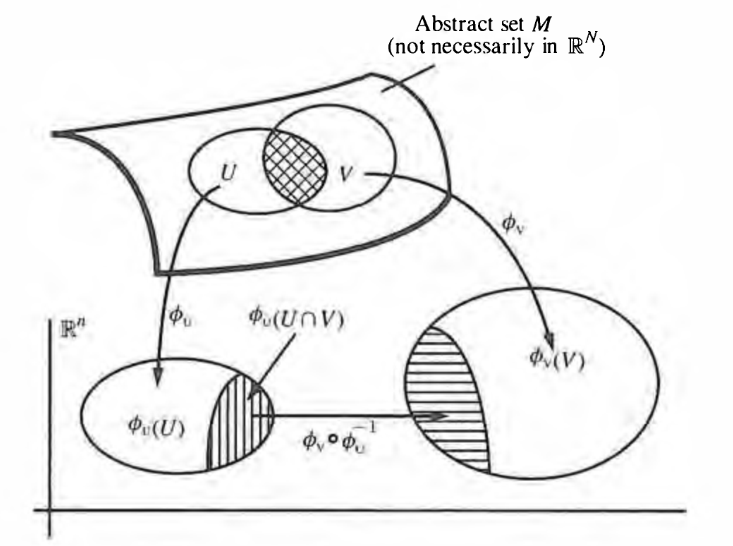

This page contains a detailed introduction to basic topology. Starting from scratch (required background is just a basic concept of sets), and amplifying motivation from analysis, it first develops standard point-set topology (topological spaces). In passing, some basics of category theory make an informal appearance, used to transparently summarize some conceptually important aspects of the theory, such as initial and final topologies and the reflection into Hausdorff and sober topological spaces. We close with discussion of the basics of topological manifolds and differentiable manifolds, hence of differential topology, laying the foundations for differential geometry.

main page: Introduction to Topology

this chapter: Introduction to Topology 1 – Point-set topology

next chapter: Introduction to Topology 2 – Basic Homotopy Theory

For introduction to more general and abstract homotopy theory see instead at Introduction to Homotopy Theory.

Context

Topology

topology (point-set topology, point-free topology)

see also differential topology, algebraic topology, functional analysis and topological homotopy theory

Basic concepts

-

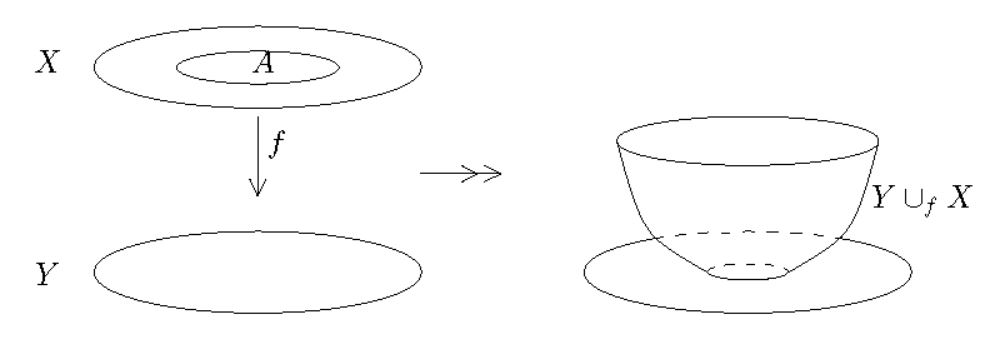

fiber space, space attachment

Extra stuff, structure, properties

-

Kolmogorov space, Hausdorff space, regular space, normal space

-

sequentially compact, countably compact, locally compact, sigma-compact, paracompact, countably paracompact, strongly compact

Examples

Basic statements

-

closed subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are equivalently compact subspaces

-

open subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are locally compact

-

compact spaces equivalently have converging subnet of every net

-

continuous metric space valued function on compact metric space is uniformly continuous

-

paracompact Hausdorff spaces equivalently admit subordinate partitions of unity

-

injective proper maps to locally compact spaces are equivalently the closed embeddings

-

locally compact and second-countable spaces are sigma-compact

Theorems

Analysis Theorems

Point-set Topology

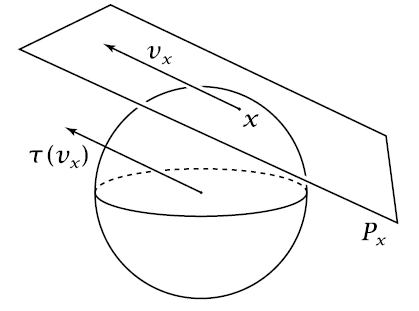

The idea of topology is to study “spaces” with “continuous functions” between them. Specifically one considers functions between sets (whence “point-set topology”, see below) such that there is a concept for what it means that these functions depend continuously on their arguments, in that their values do not “jump”. Such a concept of continuity is familiar from analysis on metric spaces, (recalled below) but the definition in topology generalizes this analytic concept and renders it more foundational, generalizing the concept of metric spaces to that of topological spaces. (def. below).

Hence, topology is the study of the category whose objects are topological spaces, and whose morphisms are continuous functions (see also remark below). This category is much more flexible than that of metric spaces, for example it admits the construction of arbitrary quotients and intersections of spaces. Accordingly, topology underlies or informs many and diverse areas of mathematics, such as functional analysis, operator algebra, manifold/scheme theory, hence algebraic geometry and differential geometry, and the study of topological groups, topological vector spaces, local rings, etc. Not the least, it gives rise to the field of homotopy theory, where one considers also continuous deformations of continuous functions themselves (“homotopies”). Topology itself has many branches, such as low-dimensional topology or topological domain theory.

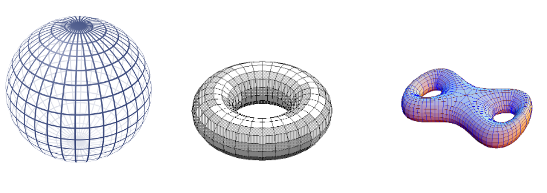

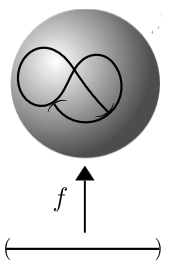

A popular imagery for the concept of a continuous function is provided by deformations of elastic physical bodies, which may be deformed by stretching them without tearing. The canonical illustration is a continuous bijective function from the torus to the surface of a coffee mug, which maps half of the torus to the handle of the coffee mug, and continuously deforms parts of the other half in order to form the actual cup. Since the inverse function to this function is itself continuous, the torus and the coffee mug, both regarded as topological spaces, are “the same” for the purposes of topology; one says they are homeomorphic.

On the other hand, there is no homeomorphism from the torus to, for instance, the sphere, signifying that these represent two topologically distinct spaces. Part of topology is concerned with studying homeomorphism-invariants of topological spaces (“topological properties”) which allow to detect by means of algebraic manipulations whether two topological spaces are homeomorphic (or more generally homotopy equivalent) or not. This is called algebraic topology. A basic algebraic invariant is the fundamental group of a topological space (discussed below), which measures how many ways there are to wind loops inside a topological space.

Beware the popular imagery of “rubber-sheet geometry”, which only captures part of the full scope of topology, in that it invokes spaces that locally still look like metric spaces (called topological manifolds, see below). But the concept of topological spaces is a good bit more general. Notably, finite topological spaces are either discrete or very much unlike metric spaces (example below); the former play a role in categorical logic. Also, in geometry, exotic topological spaces frequently arise when forming non-free quotients. In order to gauge just how many of such “exotic” examples of topological spaces beyond locally metric spaces one wishes to admit in the theory, extra “separation axioms” are imposed on topological spaces (see below), and the flavour of topology as a field depends on this choice.

Among the separation axioms, the Hausdorff space axiom is the most popular (see below). But the weaker axiom of sobriety (see below) stands out, because on the one hand it is the weakest axiom that is still naturally satisfied in applications to algebraic geometry (schemes are sober) and computer science (Vickers 89), and on the other, it fully realizes the strong roots that topology has in formal logic: sober topological spaces are entirely characterized by the union-, intersection- and inclusion-relations (logical conjunction, disjunction and implication) among their open subsets (propositions). This leads to a natural and fruitful generalization of topology to more general “purely logic-determined spaces”, called locales, and in yet more generality, toposes and higher toposes. While the latter are beyond the scope of this introduction, their rich theory and relation to the foundations of mathematics and geometry provide an outlook on the relevance of the basic ideas of topology.

In this first part we discuss the foundations of the concept of “sets equipped with topology” (topological spaces) and of continuous functions between them.

The proofs in the following freely use the principle of excluded middle, hence proof by contradiction, and in a few places they also use the axiom of choice/Zorn's lemma.

Hence we discuss topology in its traditional form with classical logic.

We do however highlight the role of frame homomorphisms (def. below) and that of sober topological spaces (def. below). These concepts pave the way to a constructive formulation of topology in terms not of topological spaces but in terms of locales (remark below). For further reading along these lines see Johnstone 83.

Apart from classical logic, we assume the usual informal concept of sets. The reader (only) needs to know the concepts of

-

complements of subsets;

-

image sets and pre-image sets under a function

;

-

unions and intersections of indexed sets of subsets .

The only rules of set theory that we use are the

For reference, we recall these:

Proposition

(images preserve unions but not in general intersections)

Let be a function between sets. Let be a set of subsets of . Then

-

(the image under of a union of subsets is the union of the images)

-

(the image under of the intersection of the subsets is contained in the intersection of the images).

The injection in the second item is in general proper. If is an injective function and if is non-empty, then this is a bijection:

Proposition

(pre-images preserve unions and intersections)

Let be a function between sets. Let be a set of subsets of . Then

-

(the pre-image under of a union of subsets is the union of the pre-images),

-

(the pre-image under of the intersection of the subsets is the intersection of the pre-images).

Proposition

Given a set and a set of subsets

then the complement of their union is the intersection of their complements

and the complement of their intersection is the union of their complements

Moreover, taking complements reverses inclusion relations:

Metric spaces

The concept of continuity was first made precise in analysis, in terms of epsilontic analysis on metric spaces, recalled as def. below. Then it was realized that this has a more elegant formulation in terms of the more general concept of open sets, this is prop. below. Adopting the latter as the definition leads to a more abstract concept of “continuous space”, this is the concept of topological spaces, def. below.

Here we briefly recall the relevant basic concepts from analysis, as a motivation for various definitions in topology. The reader who either already recalls these concepts in analysis or is content with ignoring the motivation coming from analysis should skip right away to the section Topological spaces.

Definition

A metric space is

-

a set (the “underlying set”);

-

a function (the “distance function”) from the Cartesian product of the set with itself to the non-negative real numbers

such that for all :

-

(symmetry)

-

(non-degeneracy)

Definition

Let , be a metric space. Then for every element and every a positive real number, we write

for the open ball of radius around . Similarly we write

for the closed ball of radius around . Finally we write

for the sphere of radius around .

For we also speak of the unit open/closed ball and the unit sphere.

Definition

For a metric space (def. ) then a subset is called a bounded subset if is contained in some open ball (def. )

around some of some radius .

A key source of metric spaces are normed vector spaces:

Definition

(normed vector space)

A normed vector space is

-

from the underlying set of to the non-negative real numbers,

such that for all with absolute value and all it holds true that

-

(linearity) ;

-

(non-degeneracy) if then .

Proposition

Every normed vector space becomes a metric space according to def. by setting

Examples of normed vector spaces (def. ) and hence, via prop. , of metric spaces include the following:

Example

For , the Cartesian space

carries a norm (the Euclidean norm ) given by the square root of the sum of the squares of the components:

Via prop. this gives the structure of a metric space, and as such it is called the Euclidean space of dimension .

Example

More generally, for , and , , then the Cartesian space carries the p-norm

One also sets

and calls this the supremum norm.

The graphics on the right (grabbed from Wikipedia) shows unit circles (def. ) in with respect to various p-norms.

By the Minkowski inequality, the p-norm generalizes to non-finite dimensional vector spaces such as sequence spaces and Lebesgue spaces.

Continuity

The following is now the fairly obvious definition of continuity for functions between metric spaces.

Definition

(epsilontic definition of continuity)

For and two metric spaces (def. ), then a function

is said to be continuous at a point if for every positive real number there exists a positive real number such that for all that are a distance smaller than from then their image is a distance smaller than from :

The function is said to be continuous if it is continuous at every point .

Example

(distance function from a subset is continuous)

Let be a metric space (def. ) and let be a subset of the underlying set. Define then the function

from the underlying set to the real numbers by assigning to a point the infimum of the distances from to , as ranges over the elements of :

This is a continuous function, with regarded as a metric space via its Euclidean norm (example ).

In particular the original distance function is continuous in both its arguments.

Proof

Let and let be a positive real number. We need to find a positive real number such that for with then .

For and , consider the triangle inequalities

Forming the infimum over of all terms appearing here yields

which implies

This means that we may take for instance .

Example

(rational functions are continuous)

Consider the real line regarded as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space from example .

For a polynomial, then the function

is a continuous function in the sense of def. . Hence polynomials are continuous functions.

Similarly rational functions are continuous on their domain of definition: for two polynomials, then is a continuous function.

Also for instance forming the square root is a continuous function .

On the other hand, a step function is continuous everywhere except at the finite number of points at which it changes its value, see example below.

We now reformulate the analytic concept of continuity from def. in terms of the simple but important concept of open sets:

Definition

(neighbourhood and open set)

Let be a metric space (def. ). Say that:

-

A neighbourhood of a point is a subset which contains some open ball around (def. ).

-

An open subset of is a subset such that for every it also contains an open ball around (def. ).

-

An open neighbourhood of a point is a neighbourhood of which is also an open subset, hence equivalently this is any open subset of that contains .

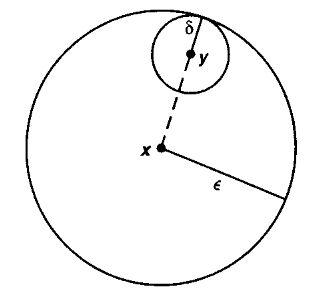

The following picture shows a point , some open balls containing it, and two of its neighbourhoods :

graphics grabbed from Munkres 75

Example

(the empty subset is open)

Notice that for a metric space, then the empty subset is always an open subset of according to def. . This is because the clause for open subsets says that “for every point there exists…”, but since there is no in , this clause is always satisfied in this case.

Conversely, the entire set is always an open subset of .

Example

(open/closed intervals)

Regard the real numbers as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ).

For consider the following subsets:

-

(open interval)

-

(half-open interval)

-

(half-open interval)

-

(closed interval)

The first of these is an open subset according to def. , the other three are not. The first one is called an open interval, the last one a closed interval and the middle two are called half-open intervals.

Similarly for one considers

-

(unbounded open interval)

-

(unbounded open interval)

-

(unbounded half-open interval)

-

(unbounded half-open interval)

The first two of these are open subsets, the last two are not.

For completeness we may also consider

We may now rephrase the analytic definition of continuity entirely in terms of open subsets (def. ):

Proposition

(rephrasing continuity in terms of open sets)

Let and be two metric spaces (def. ). Then a function is continuous in the epsilontic sense of def. precisely if it has the property that its pre-images of open subsets of (in the sense of def. ) are open subsets of :

principle of continuity

Continuous pre-Images of open subsets are open.

Proof

Observe, by direct unwinding the definitions, that the epsilontic definition of continuity (def. ) says equivalently in terms of open balls (def. ) that is continuous at precisely if for every open ball around an image point, there exists an open ball around the corresponding pre-image point which maps into it:

With this observation the proof immediate. For the record, we spell it out:

First assume that is continuous in the epsilontic sense. Then for any open subset and any point in the pre-image, we need to show that there exists an open neighbourhood of in .

That is open in means by definition that there exists an open ball in around for some radius . By the assumption that is continuous and using the above observation, this implies that there exists an open ball in such that , hence such that . Hence this is an open ball of the required kind.

Conversely, assume that the pre-image function takes open subsets to open subsets. Then for every and an open ball around its image, we need to produce an open ball around such that .

But by definition of open subsets, is open, and therefore by assumption on its pre-image is also an open subset of . Again by definition of open subsets, this implies that it contains an open ball as required.

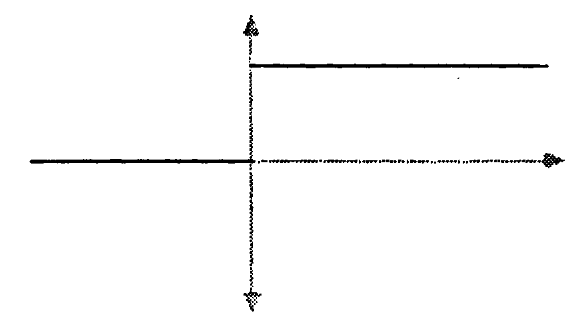

Example

Consider as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) and consider the step function

graphics grabbed from Vickers 89

Consider then for the open interval , an open subset according to example . The preimage of this open subset is

By example , all except the last of these pre-images listed are open subsets.

The failure of the last of the pre-images to be open witnesses that the step function is not continuous at .

Compactness

A key application of metric spaces in analysis is that they allow a formalization of what it means for an infinite sequence of elements in the metric space (def. below) to converge to a limit of a sequence (def. below). Of particular interest are therefore those metric spaces for which each sequence has a converging subsequence: the sequentially compact metric spaces (def. ).

We now briefly recall these concepts from analysis. Then, in the above spirit, we reformulate their epsilontic definition in terms of open subsets. This gives a useful definition that generalizes to topological spaces, the compact topological spaces discussed further below.

Definition

(sequence)

Given a set , then a sequence of elements in is a function

from the natural numbers to .

A sub-sequence of such a sequence is a sequence of the form

Definition

(convergence to limit of a sequence)

Let be a metric space (def. ). Then a sequence

in the underlying set (def. ) is said to converge to a point , denoted

if for every positive real number , there exists a natural number , such that all elements in the sequence after the th one have distance less than from .

Here the point is called the limit of the sequence. Often one writes for this point.

Definition

Given a metric space (def. ), then a sequence of points in (def. )

is called a Cauchy sequence if for every positive real number there exists a natural number such that the distance between any two elements of the sequence beyond the th one is less than

Definition

A metric space (def. ), for which every Cauchy sequence (def. ) converges (def. ) is called a complete metric space.

A normed vector space, regarded as a metric space via prop. that is complete in this sense is called a Banach space.

Finally recall the concept of compactness of metric spaces via epsilontic analysis:

Definition

(sequentially compact metric space)

A metric space (def. ) is called sequentially compact if every sequence in has a subsequence (def. ) which converges (def. ).

The key fact to translate this epsilontic definition of compactness to a concept that makes sense for general topological spaces (below) is the following:

Proposition

(sequentially compact metric spaces are equivalently compact metric spaces)

For a metric space (def. ) the following are equivalent:

-

for every set of open subsets of (def. ) which cover in that , then there exists a finite subset of these open subsets which still covers in that also .

The proof of prop. is most conveniently formulated with some of the terminology of topology in hand, which we introduce now. Therefore we postpone the proof to below.

In summary prop. and prop. show that the purely combinatorial and in particular non-epsilontic concept of open subsets captures a substantial part of the nature of metric spaces in analysis. This motivates to reverse the logic and consider more general “spaces” which are only characterized by what counts as their open subsets. These are the topological spaces which we turn to now in def. (or, more generally, these are the “locales”, which we briefly consider below in remark ).

Topological spaces

Due to prop. we should pay attention to open subsets in metric spaces. It turns out that the following closure property, which follow directly from the definitions, is at the heart of the concept:

Proposition

(closure properties of open sets in a metric space)

The collection of open subsets of a metric space as in def. has the following properties:

-

The union of any set of open subsets is again an open subset.

-

The intersection of any finite number of open subsets is again an open subset.

Remark

(empty union and empty intersection)

Notice the degenerate case of unions and intersections of subsets for the case that they are indexed by the empty set :

-

the empty union is the empty set itself;

-

the empty intersection is all of .

(The second of these may seem less obvious than the first. We discuss the general logic behind these kinds of phenomena below.)

This way prop. is indeed compatible with the degenerate cases of examples of open subsets in example .

Proposition motivates the following generalized definition, which abstracts away from the concept of metric space just its system of open subsets:

Definition

Given a set , then a topology on is a collection of subsets of called the open subsets, hence a subset of the power set

such that this is closed under forming

-

finite intersections;

-

arbitrary unions.

- the empty set is in (being the union of no subsets)

and

- the whole set itself is in (being the intersection of no subsets).

A set equipped with such a topology is called a topological space.

Remark

In the field of topology it is common to eventually simply say “space” as shorthand for “topological space”. This is especially so as further qualifiers are added, such as “Hausdorff space” (def. below). But beware that there are other kinds of spaces in mathematics.

In view of example below one generalizes the terminology from def. as follows:

Definition

Let be a topological space and let be a point. A neighbourhood of is a subset which contains an open subset that still contains .

An open neighbourhood is a neighbourhood that is itself an open subset, hence an open neighbourhood of is the same as an open subset containing .

Remark

The simple definition of open subsets in def. and the simple implementation of the principle of continuity below in def. gives the field of topology its fundamental and universal flavor. The combinatorial nature of these definitions makes topology be closely related to formal logic. This becomes more manifest still for the “sober topological space” discussed below. For more on this perspective see the remark on locales below, remark . An introductory textbook amplifying this perspective is (Vickers 89).

Before we look at first examples below, here is some common further terminology regarding topological spaces:

There is an evident partial ordering on the set of topologies that a given set may carry:

Definition

Let be a set, and let be two topologies on , hence two choices of open subsets for , making it a topological space. If

hence if every open subset of with respect to is also regarded as open by , then one says that

With any kind of structure on sets, it is of interest how to “generate” such structures from a small amount of data:

Definition

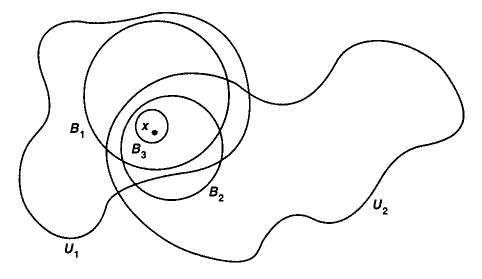

Let be a topological space, def. , and let

be a subset of its set of open subsets. We say that

-

is a basis for the topology if every open subset is a union of elements of ;

-

is a sub-basis for the topology if every open subset is a union of finite intersections of elements of .

Often it is convenient to define topologies by defining some (sub-)basis as in def. . Examples are the the metric topology below, example , the binary product topology in def. below, and the compact-open topology on mapping spaces below in def. . To make use of this, we need to recognize sets of open subsets that serve as the basis for some topology:

Lemma

(recognition of topological bases)

Let be a set.

-

A collection of subsets of is a basis for some topology (def. ) precisely if

-

every point of is contained in at least one element of ;

-

for every two subsets and for every point in their intersection, there exists a that contains and is contained in the intersection: .

-

-

A subset of open subsets is a sub-basis for a topology on precisely if is the coarsest topology (def. ) which contains .

Examples

We discuss here some basic examples of topological spaces (def. ), to get a feeling for the scope of the concept. But topological spaces are ubiquituous in mathematics, so that there are many more examples and many more classes of examples than could be listed. As we further develop the theory below, we encounter more examples, and more classes of examples. Below in Universal constructions we discuss a very general construction principle of new topological space from given ones.

First of all, our motivating example from above now reads as follows:

Example

Let be a metric space (def. ). Then the collection of its open subsets in def. constitutes a topology on the set , making it a topological space in the sense of def. . This is called the metric topology.

The open balls in a metric space constitute a basis of a topology (def. ) for the metric topology.

While the example of metric space topologies (example ) is the motivating example for the concept of topological spaces, it is important to notice that the concept of topological spaces is considerably more general, as some of the following examples show.

The following simplistic example of a (metric) topological space is important for the theory (for instance in prop. ):

Example

(empty space and point space)

On the empty set there exists a unique topology making it a topological space according to def. . We write also

for the resulting topological space, which we call the empty topological space.

On a singleton set there exists a unique topology making it a topological space according to def. , namelyf

We write

for this topological space and call it the point topological space.

This is equivalently the metric topology (example ) on , regarded as the 0-dimensional Euclidean space (example ).

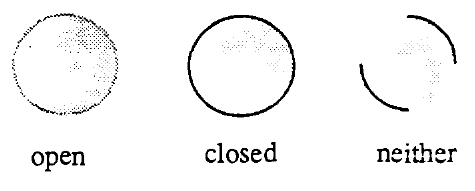

Example

On the 2-element set there are (up to permutation of elements) three distinct topologies:

-

the codiscrete topology (def. ) ;

-

the discrete topology (def. ), ;

-

the Sierpinski space topology .

Example

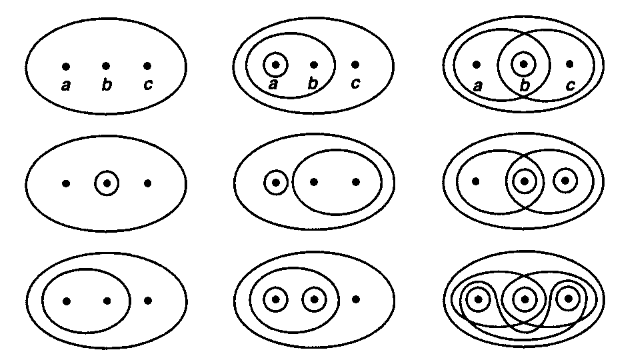

The following shows all the topologies on the 3-element set (up to permutation of elements)

graphics grabbed from Munkres 75

Example

(discrete and co-discrete topology)

Let be any set. Then there are always the following two extreme possibilities of equipping with a topology in the sense of def. , and hence making it a topological space:

-

the set of all open subsets;

this is called the discrete topology on , it is the finest topology (def. ) on ,

we write for the resulting topological space;

-

the set containing only the empty subset of and all of itself;

this is called the codiscrete topology on , it is the coarsest topology (def. ) on ,

we write for the resulting topological space.

The reason for this terminology is best seen when considering continuous functions into or out of these (co-)discrete topological spaces, we come to this in example below.

Example

Given a set , then the cofinite topology or finite complement topology on is the topology (def. ) whose open subsets are precisely

-

all cofinite subsets (i.e. those such that the complement is a finite set);

-

the empty set.

If is itself a finite set (but not otherwise) then the cofinite topology on coincides with the discrete topology on (example ).

We now consider basic construction principles of new topological spaces from given ones:

-

disjoint union spaces (example )

-

subspaces (example ),

-

quotient spaces (example )

-

product spaces (example ).

Below in Universal constructions we will recognize these as simple special cases of a general construction principle.

Example

For a set of topological spaces, then their disjoint union

is the topological space whose underlying set is the disjoint union of the underlying sets of the summand spaces, and whose open subsets are precisely the disjoint unions of the open subsets of the summand spaces.

In particular, for any index set, then the disjoint union of copies of the point space (example ) is equivalently the discrete topological space (example ) on that index set:

Example

Let be a topological space, and let be a subset of the underlying set. Then the corresponding topological subspace has as its underlying set, and its open subsets are those subsets of which arise as restrictions of open subsets of .

(This is also called the initial topology of the inclusion map. We come back to this below in def. .)

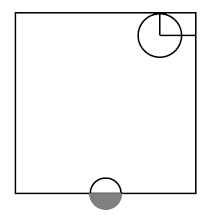

The picture on the right shows two open subsets inside the square, regarded as a topological subspace of the plane :

graphics grabbed from Munkres 75

Example

Let be a topological space (def. ) and let

be an equivalence relation on its underlying set. Then the quotient topological space has

- as underlying set the quotient set , hence the set of equivalence classes,

and

-

a subset is declared to be an open subset precisely if its preimage under the canonical projection map

is open in .

(This is also called the final topology of the projection . We come back to this below in def. . )

Often one considers this with input datum not the equivalence relation, but any surjection

of sets. Of course this identifies with . Hence the quotient topology on the codomain set of a function out of any topological space has as open subsets those whose pre-images are open.

To see that this indeed does define a topology on it is sufficient to observe that taking pre-images commutes with taking unions and with taking intersections.

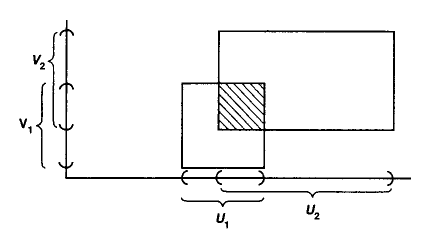

Example

(binary product topological space)

For and two topological spaces, then their binary product topological space has as underlying set the Cartesian product of the corresponding two underlying sets, and its topology is generated from the basis (def. ) given by the Cartesian products of the opens .

graphics grabbed from Munkres 75

Beware for non-finite products, the descriptions of the product topology is not as simple. This we turn to below in example , after introducing the general concept of limits in the category of topological spaces.

The following examples illustrate how all these ingredients and construction principles may be combined.

The following example examines in more detail below in example , after we have introduced the concept of homeomorphisms below.

Example

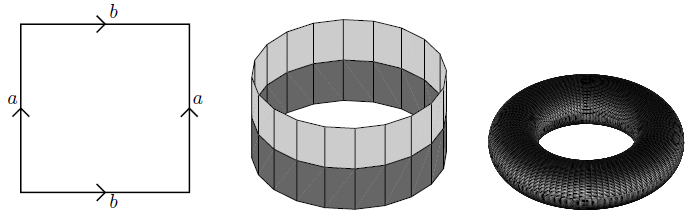

Consider the real numbers as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) and hence as a topological space via the corresponding metric topology (example ). Moreover, consider the closed interval from example , regarded as a subspace (def. ) of .

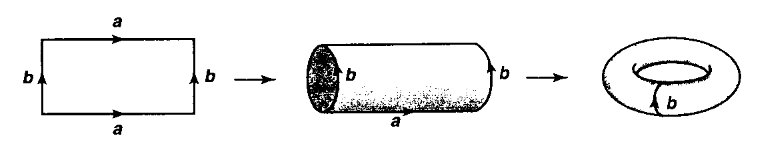

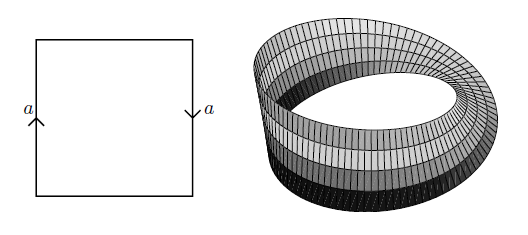

The product space (example ) of this interval with itself

is a topological space modelling the closed square. The quotient space (example ) of that by the relation which identifies a pair of opposite sides is a model for the cylinder. The further quotient by the relation that identifies the remaining pair of sides yields a model for the torus.

graphics grabbed from Munkres 75

Example

(spheres and disks)

For write

-

for the n-disk, the closed unit ball (def. ) in the -dimensional Euclidean space (example ) and equipped with the induced subspace topology (example ) of the corresponding metric topology (example );

-

for the (n-1)-sphere (def. ) also equipped with the corresponding subspace topology;

-

for the continuous function that exhibits this boundary inclusion.

Notice that

-

is the empty topological space (example );

-

is the disjoint union space (example ) of the point topological space (example ) with itself, equivalently the discrete topological space on two elements (example ).

The following important class of topological spaces form the foundation of algebraic geometry:

Example

(Zariski topology on affine space)

Let be a field, let , and write for the set of polynomials in variables over .

For a subset of polynomials, let the subset of the -fold Cartesian product of the underlying set of (the vanishing set of ) be the subset of points on which all these polynomials jointly vanish:

These subsets are called the Zariski closed subsets.

Write

for the set of complements of the Zariski closed subsets. These are called the Zariski open subsets of .

The Zariski open subsets of form a topology (def. ), called the Zariski topology. The resulting topological space

is also called the -dimensional affine space over .

More generally:

Example

(Zariski topology on the prime spectrum of a commutative ring)

Let be a commutative ring. Write for its set of prime ideals. For any subset of elements of the ring, consider the subsets of those prime ideals that contain :

These are called the Zariski closed subsets of . Their complements are called the Zariski open subsets.

Then the collection of Zariski open subsets in its set of prime ideals

satisfies the axioms of a topology (def. ), the Zariski topology.

This topological space

is called (the space underlying) the prime spectrum of the commutative ring.

Closed subsets

The complements of open subsets in a topological space are called closed subsets (def. below). This simple definition indeed captures the concept of closure in the analytic sense of convergence of sequences (prop. below). Of particular interest for the theory of topological spaces in the discussion of separation axioms below are those closed subsets which are “irreducible” (def. below). These happen to be equivalently the “frame homomorphisms” (def. ) to the frame of opens of the point (prop. below).

Definition

Let be a topological space (def. ).

-

A subset is called a closed subset if its complement is an open subset:

graphics grabbed from Vickers 89

-

If a singleton subset is closed, one says that is a closed point of .

-

Given any subset , then its topological closure is the smallest closed subset containing :

-

A subset such that is called a dense subset of .

Often it is useful to reformulate def. of closed subsets as follows:

Lemma

(alternative characterization of topological closure)

Let be a topological space and let be a subset of its underlying set. Then a point is contained in the topological closure (def. ) precisely if every open neighbourhood of (def. ) intersects :

Proof

Due to de Morgan duality (prop. ) we may rephrase the definition of the topological closure as follows:

Proposition

(closure of a finite union is the union of the closures)

For a finite set and a finite set of subsets of a topological space, we have

Proof

By lemma we use that a point is in the closure of a set precisely if every open neighbourhood (def. ) of the point intersects the set.

Hence in one direction

because if every neighbourhood of a point intersects some , then every neighbourhood intersects their union.

The other direction

is equivalent by de Morgan duality to

On left now we have the point for which there exists for each a neighbourhood which does not intersect . Since is finite, the intersection is still an open neighbourhood of , and such that it intersects none of the , hence such that it does not intersect their union. This implis that the given point is contained in the set on the right.

Definition

(topological interior and boundary)

Let be a topological space (def. ) and let be a subset. Then the topological interior of is the largest open subset still contained in , :

The boundary of is the complement of its interior inside its topological closure (def. ):

Lemma

(duality between closure and interior)

Let be a topological space and let be a subset. Then the topological interior of (def. ) is the same as the complement of the topological closure of the complement of :

and conversely

Example

(topological closure and interior of closed and open intervals)

Regard the real numbers as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) and equipped with the corresponding metric topology (example ) . Let . Then the topological interior (def. ) of the closed interval (example ) is the open interval , moreover the closed interval is its own topological closure (def. ) and the converse holds (by lemma ):

Hence the boundary of the closed interval is its endpoints, while the boundary of the open interval is empty

The terminology “closed” subspace for complements of opens is justified by the following statement, which is a further example of how the combinatorial concept of open subsets captures key phenomena in analysis:

Proposition

(convergence in closed subspaces)

Let be a metric space (def. ), regarded as a topological space via example , and let be a subset. Then the following are equivalent:

-

is a closed subspace according to def. .

-

For every sequence (def. ) with elements in , which converges as a sequence in (def. ) to some , we have .

Proof

First assume that is closed and that for some . We need to show that then . Suppose it were not, hence that . Since, by assumption on , this complement is an open subset, it would follow that there exists a real number such that the open ball around of radius were still contained in the complement: . But since the sequence is assumed to converge in , this would mean that there exists such that all are in , hence in . This contradicts the assumption that all are in , and hence we have proved by contradiction that .

Conversely, assume that for all sequences in that converge to some then . We need to show that then is closed, hence that is an open subset, hence that for every we may find a real number such that the open ball around of radius is still contained in . Suppose on the contrary that such did not exist. This would mean that for each with then the intersection were non-empty. Hence then we could choose points in these intersections. These would form a sequence which clearly converges to the original , and so by assumption we would conclude that , which violates the assumption that . Hence we proved by contradiction is in fact open.

Often one considers closed subsets inside a closed subspace. The following is immediate, but useful.

Lemma

(subsets are closed in a closed subspace precisely if they are closed in the ambient space)

Let be a topological space (def. ), and let be a closed subset (def. ), regarded as a topological subspace (example ). Then a subset is a closed subset of precisely if it is closed as a subset of .

Proof

If is closed in this means equivalently that there is an open subset in such that

But by the definition of the subspace topology, this means equivalently that there is a subset which is open in such that . Hence the above is equivalent to the existence of an open subset such that

But now the condition that itself is a closed subset of means equivalently that there is an open subset with . Hence the above is equivalent to the existence of two open subsets such that

Since the union is again open, this implies that is closed in .

Conversely, that is closed in means that there exists an open with . This means that , and since is open in by definition of the subspace topology, this means that is closed in .

A special role in the theory is played by the “irreducible” closed subspaces:

Definition

A closed subset (def. ) of a topological space is called irreducible if it is non-empty and not the union of two closed proper (i.e. smaller) subsets. In other words, a non-empty closed subset is irreducible if whenever are two closed subspace such that

then or .

Example

(closures of points are irreducible)

For a point inside a topological space, then the closure of the singleton subset is irreducible (def. ).

Example

(no nontrivial closed irreducibles in metric spaces)

Let be a metric space, regarded as a topological space via its metric topology (example ). Then every point is closed (def ), hence every singleton subset is irreducible according to def. .

Let be the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) with its metric topology (example ). Then for the closed interval (example ) is not irreducible, since for any with it is the union of two smaller closed subintervals:

In fact we will see below (prop. ) that in a metric space the singleton subsets are precisely the only irreducible closed subsets.

Often it is useful to re-express the condition of irreducibility of closed subspaces in terms of complementary open subsets:

Proposition

(irreducible closed subsets in terms of prime open subsets)

Let be a topological space, and let be a proper open subset of , hence so that the complement is a non-empty closed subspace. Then is irreducible in the sense of def. precisely if whenever are open subsets with then or :

The open subsets with this property are also called the prime open subsets in .

Proof

Observe that every closed subset may be exhibited as the complement

of some open subset with respect to . Observe that under this identification the condition that is equivalent to the condition that , because it is equivalent to the equation labeled in the following sequence of equations:

Similarly, the condition that is equivalent to the condition that , because it is equivalent to the equality in the following sequence of equalities:

Under these identifications, the two conditions are manifestly the same.

We consider yet another equivalent characterization of irreducible closed subsets, prop. below, which will be needed in the discussion of the separation axioms further below. Stating this requires the following concept of “frame” homomorphism, the natural kind of homomorphisms between topological spaces if we were to forget the underlying set of points of a topological space, and only remember the set with its operations induced by taking finite intersections and arbitrary unions:

Definition

(frame homomorphisms)

Let and be topological spaces (def. ). Then a function

between their sets of open subsets is called a frame homomorphism from to if it preserves

-

arbitrary unions;

In other words, is a frame homomorphism precisely if

-

for every set and every -indexed set of elements of , then

-

for every finite set and every -indexed set of elements in , then

Remark

(frame homomorphisms preserve inclusions)

A frame homomorphism as in def. necessarily also preserves inclusions in that

-

for every inclusion with then

This is because inclusions are witnessed by unions

or alternatively because inclusions are witnessed by finite intersections:

Example

(pre-images of continuous functions are frame homomorphisms)

Let and be two topological spaces. One way to obtain a function between their sets of open subsets

is to specify a function

of their underlying sets, and take to be the pre-image operation. A priori this is a function of the form

and hence in order for this to co-restrict to when restricted to we need to demand that, under , pre-images of open subsets of are open subsets of . Below in def. we highlight these as the continuous functions between topological spaces.

In this case then

is a frame homomorphism from to in the sense of def. , by prop. .

For the following recall from example the point topological space .

Proposition

(irreducible closed subsets are equivalently frame homomorphisms to opens of the point)

For a topological space, then there is a natural bijection between the irreducible closed subspaces of (def. ) and the frame homomorphisms from to , and this bijection is given by

where is the union of all elements such that :

See also (Johnstone 82, II 1.3).

Proof

First we need to show that the function is well defined in that given a frame homomorphism then is indeed an irreducible closed subspace.

To that end observe that:

If there are two elements with then or .

This is because

where the first equality holds because preserves finite intersections by def. , the inclusion holds because respects inclusions by remark , and the second equality holds because preserves arbitrary unions by def. . But in the intersection of two open subsets is empty precisely if at least one of them is empty, hence or . But this means that or , as claimed.

Now according to prop. the condition identifies the complement as an irreducible closed subspace of .

Conversely, given an irreducible closed subset , define by

This does preserve

-

arbitrary unions

because precisely if which is the case precisely if all , which means that all and because ;

while as soon as one of the is not contained in , which means that one of the which means that ;

-

finite intersections

because if , then by or , whence or , whence with also ;

while if is not contained in then neither nor is contained in and hence with also .

Hence this is indeed a frame homomorphism .

Finally, it is clear that these two operations are inverse to each other.

Continuous functions

With the concept of topological spaces in hand (def. ) it is now immediate to formally implement in abstract generality the statement of prop. :

principle of continuity

Continuous pre-Images of open subsets are open.

Definition

(continuous function)

A continuous function between topological spaces (def. )

is a function between the underlying sets,

such that pre-images under of open subsets of are open subsets of .

We may equivalently state this in terms of closed subsets:

Proposition

Let and be two topological spaces (def. ). Then a function

between the underlying sets is continuous in the sense of def. precisely if pre-images under of closed subsets of (def. ) are closed subsets of .

Proof

This follows since taking pre-images commutes with taking complements.

Before looking at first examples of continuous functions below we consider now an informal remark on the resulting global structure, the “category of topological spaces”, remark below. This is a language that serves to make transparent key phenomena in topology which we encounter further below, such as the Tn-reflection (remark below), and the universal constructions.

Remark

(concrete category of topological spaces)

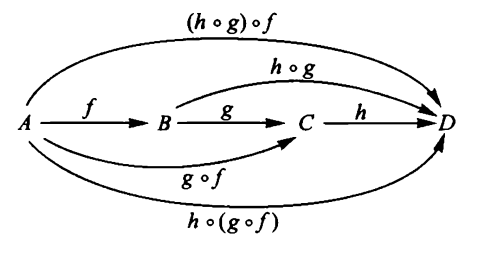

For three topological spaces and for

two continuous functions (def. ) then their composition

is clearly itself again a continuous function from to .

Moreover, this composition operation is clearly associative, in that for

three continuous functions, then

Finally, the composition operation is also clearly unital, in that for each topological space there exists the identity function and for any continuous function then

One summarizes this situation by saying that:

-

topological spaces constitute the objects,

-

continuous functions constitute the morphisms (homomorphisms)

of a category, called the category of topological spaces (“Top” for short).

It is useful to depict collections of objects with morphisms between them by diagrams, like this one:

graphics grabbed from Lawvere-Schanuel 09.

There are other categories. For instance there is the category of sets (“Set” for short) whose

The two categories Top and Set are different, but related. After all,

-

an object of Top (hence a topological space) is an object of Set (hence a set) equipped with extra structure (namely with a topology);

-

a morphism in Top (hence a continuous function) is a morphism in Set (hence a plain function) with the extra property that it preserves this extra structure.

Hence we have the underlying set assigning function

from the class of topological spaces to the class of sets. But more is true: every continuous function between topological spaces is, by definition, in particular a function on underlying sets:

and this assignment (trivially) respects the composition of morphisms and the identity morphisms.

Such a function between classes of objects of categories, which is extended to a function on the sets of homomorphisms between these objects in a way that respects composition and identity morphisms is called a functor. If we write an arrow between categories

then it is understood that we mean not just a function between their classes of objects, but a functor.

The functor at hand has the special property that it does not do much except forgetting extra structure, namely the extra structure on a set given by a choice of topology . One also speaks of a forgetful functor.

This is intuitively clear, and we may easily formalize it: The functor has the special property that as a function between sets of homomorphisms (“hom sets”, for short) it is injective. More in detail, given topological spaces and then the component function of from the set of continuous function between these spaces to the set of plain functions between their underlying sets

is an injective function, including the continuous functions among all functions of underlying sets.

A functor with this property, that its component functions between all hom-sets are injective, is called a faithful functor.

A category equipped with a faithful functor to Set is called a concrete category.

Hence Top is canonically a concrete category.

Example

(product topological space construction is functorial)

For and two categories as in remark (for instance Top or Set) then we obtain a new category denoted and called their product category whose

-

morphisms are pairs with a morphism of

and a morphism of ,

-

composition of morphisms is defined pairwise .

This concept secretly underlies the construction of product topological spaces:

Let , , and be topological spaces. Then for all pairs of continuous functions

and

the canonically induced function on Cartesian products of sets

is clearly a continuous function with respect to the binary product space topologies (def. )

Moreover, this construction respects identity functions and composition of functions in both arguments.

In the language of category theory (remark ), this is summarized by saying that the product topological space construction extends to a functor from the product category of the category Top with itself to itself:

Examples

We discuss here some basic examples of continuous functions (def. ) between topological spaces (def. ) to get a feeling for the nature of the concept. But as with topological spaces themselves, continuous functions between them are ubiquitous in mathematics, and no list will exhaust all classes of examples. Below in the section Universal constructions we discuss a general principle that serves to produce examples of continuous functions with prescribed “universal properties”.

Example

(point space is terminal)

For any topological space, then there is a unique continuous function

-

from the empty topological space (def. )

-

from to the point topological space (def. ).

In the language of category theory (remark ), this says that

-

the empty topological space is the initial object

-

the point space is the terminal object

in the category Top of topological spaces. We come back to this below in example .

Example

(constant continuous functions)

For a topological space then for any element of the underlying set, there is a unique continuous function (which we denote by the same symbol)

from the point topological space (def. ), whose image in is that element. Hence there is a natural bijection

between the continuous functions from the point to any topological space, and the underlying set of that topological space.

More generally, for and two topological spaces, then a continuous function between them is called a constant function with value some point if it factors through the point spaces as

Definition

For , two topological spaces, then a continuous function (def. ) is called locally constant if every point has a neighbourhood (def. ) on which the function is constant.

Example

(continuous functions into and out of discrete and codiscrete spaces)

Let be a set and let be a topological space. Recall from example

on the underlying set . Then continuous functions (def. ) into/out of these satisfy:

-

every function (of sets) out of a discrete space is continuous;

-

every function (of sets) into a codiscrete space is continuous.

Also:

- every continuous function into a discrete space is locally constant (def. ).

Example

(diagonal)

For a set, its diagonal is the function from to the Cartesian product of with itself, given by

For a topological space, then the diagonal is a continuous function to the product topological space (def. ) of with itself.

To see this, it is sufficient to see that the preimages of basic opens in are in . But these pre-images are the intersections , which are open by the axioms on the topology .

Example

Let be a continuous function.

Write for the image of on underlying sets, and consider the resulting factorization of through on underlying sets:

There are the following two ways to topologize the image such as to make this a sequence of two continuous functions:

-

By example inherits a subspace topology from which evidently makes the inclusion a continuous function.

Observe that this also makes a continuous function: An open subset of in this case is of the form for , and , which is open in since is continuous.

-

By example inherits a quotient topology from which evidently makes the surjection a continuous function.

Observe that this also makes a continuous function: The preimage under this map of an open subset is the restriction , and the pre-image of that under is , as before, which is open since is continuous, and therefore is open in the quotient topology.

Beware, in general a continuous function itself (as opposed to its pre-image function) neither preserves open subsets, nor closed subsets, as the following examples show:

Example

Regard the real numbers as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) equipped with the metric topology (example ). For the constant function (example )

maps every open subset to the singleton set , which is not open.

Example

Write for the set of real numbers equipped with its discrete topology (def. ) and for the set of real numbers equipped with its Euclidean metric topology (example , example ). Then the identity function on the underlying sets

is a continuous function (a special case of example ). A singleton subset is open, but regarded as a subset it is not open.

Example

Consider the set of real numbers equipped with its Euclidean metric topology (example , example ). The exponential function

maps all of (which is a closed subset, since ) to the open interval , which is not closed.

Those continuous functions that do happen to preserve open or closed subsets get a special name:

Definition

(open maps and closed maps)

A continuous function (def. ) is called

-

an open map if the image under of an open subset of is an open subset of ;

-

a closed map if the image under of a closed subset of (def. ) is a closed subset of .

Example

(image projections of open/closed maps are themselves open/closed)

If a continuous function is an open map or closed map (def. ) then so its its image projection , respectively, for regarded with its subspace topology (example ).

Proof

If is an open map, and is an open subset, so that is also open in , then, since , it is also still open in the subspace topology, hence is an open map.

If is a closed map, and is a closed subset so that also is a closed subset, then the complement is open in and hence is open in the subspace topology, which means that is closed in the subspace topology.

Example

(projections are open continuous functions )

For and two topological spaces, then the projection maps

out of their product topological space (def. )

are open continuous functions (def. ).

This is because, by definition, every open subset in the product space topology is a union of products of open subsets and in the factor spaces

and because taking the image of a function preserves unions of subsets

Below in prop. we find a large supply of closed maps.

Sometimes it is useful to recognize quotient topological space projections via saturated subsets (essentially another term for pre-images of underlying sets):

Definition

Let be a function of sets. Then a subset is called an -saturated subset (or just saturated subset, if is understood) if is the pre-image of its image:

Here is also called the -saturation of .

Example

(pre-images are saturated subsets)

For any function of sets, and any subset of , then the pre-image is an -saturated subset of (def. ).

Observe that:

Lemma

Let be a function. Then a subset is -saturated (def. ) precisely if its complement is saturated.

Proposition

(recognition of quotient topologies)

A continuous function (def. )

whose underlying function is surjective exhibits as the corresponding quotient topology (def. ) precisely if sends open and -saturated subsets in (def. ) to open subsets of . By lemma this is the case precisely if it sends closed and -saturated subsets to closed subsets.

We record the following technical lemma about saturated subspaces, which we will need below to prove prop. .

Lemma

(saturated open neighbourhoods of saturated closed subsets under closed maps)

Let

-

be a closed map (def. );

-

be a closed subset of (def. ) which is -saturated (def. );

-

be an open subset containing ;

then there exists a smaller open subset still containing

and such that is still -saturated.

Proof

We claim that the complement of by the -saturation (def. ) of the complement of by

has the desired properties. To see this, observe first that

-

the complement is closed, since is assumed to be open;

-

hence the image is closed, since is assumed to be a closed map;

-

hence the pre-image is closed, since is continuous (using prop. ), therefore its complement is indeed open;

-

this pre-image is saturated (by example ) and hence also its complement is saturated (by lemma ).

Therefore it now only remains to see that .

By de Morgan's law (prop. ) the inclusion is equivalent to the inclusion , which is clearly the case.

The inclusion is equivalent to . Since is saturated by assumption, this is equivalent to . This in turn holds precisely if . Since is saturated, this holds precisely if , and this is true by the assumption that .

Homeomorphisms

With the objects (topological spaces) and the morphisms (continuous functions) of the category Top thus defined (remark ), we obtain the concept of “sameness” in topology. To make this precise, one says that a morphism

in a category is an isomorphism if there exists a morphism going the other way around

which is an inverse in the sense that both its compositions with yield an identity morphism:

Since such is unique if it exists, one often writes “” for this inverse morphism.

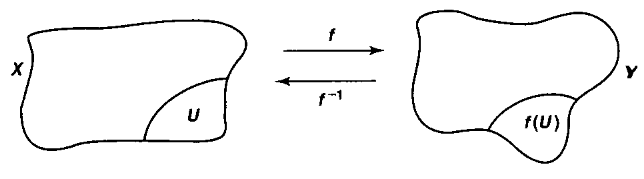

Definition

An isomorphism in the category Top (remark ) of topological spaces (def. ) with continuous functions between them (def. ) is called a homeomorphism.

Hence a homeomorphism is a continuous function

between two topological spaces , such that there exists another continuous function the other way around

such that their composites are the identity functions on and , respectively:

graphics grabbed from Munkres 75

We notationally indicate that a continuous function is a homeomorphism by the symbol “”.

If there is some, possibly unspecified, homeomorphism between topological spaces and , then we also write

and say that the two topological spaces are homeomorphic.

A property/predicate of topological spaces which is invariant under homeomorphism in that

is called a topological property or topological invariant.

Remark

(notation for homeomorphisms)

Beware the following notation:

-

In topology the notation generally refers to the pre-image function of a given function , while if is a homeomorphism (def. ), it is also used for the inverse function of . This abuse of notation is convenient: If happens to be a homeomorphism, then the pre-image of a subsets under is its image under the inverse function .

-

Many authors strictly distinguish the symbols “” and “” and use the former to denote homeomorphisms and the latter to refer to homotopy equivalences (which we consider in part 2). We use either symbol (but mostly “”) for “isomorphism” in whatever the ambient category may be and try to make that context always unambiguously explicit.

Remark

If is a homeomorphism (def. ) with inverse continuous function , then

-

also is a homeomophism, with inverse continuous function ;

-

the underlying function of sets of a homeomorphism is necessarily a bijection, with inverse bijection .

But beware that not every continuous function which is bijective on underlying sets is a homeomorphism. While an inverse function will exists on the level of functions of sets, this inverse may fail to be continuous:

Counter Example

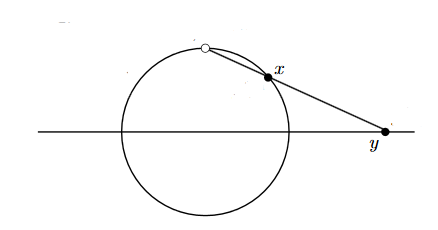

Consider the continuous function

from the half-open interval (def. ) to the unit circle (def. ), regarded as a topological subspace (example ) of the Euclidean plane (example ).

The underlying function of sets of is a bijection. The inverse function of sets however fails to be continuous at . Hence this is not a homeomorphism.

Indeed, below we see that the two topological spaces and are distinguished by topological invariants, meaning that they cannot be homeomorphic via any (other) choice of homeomorphism. For example is a compact topological space (def. ) while is not, and has a non-trivial fundamental group, while that of is trivial (this prop.).

Below in example we discuss a practical criterion under which continuous bijections are homeomorphisms after all. But immediate from the definitions is the following characterization:

Proposition

(homeomorphisms are the continuous and open bijections)

Let be a continuous function between topological spaces (def. ). Then the following are equivalence:

-

is a homeomorphism;

-

is a bijection and a closed map (def. ).

Proof

It is clear from the definition that a homeomorphism in particular has to be a bijection. The condition that the inverse function be continuous means that the pre-image function of sends open subsets to open subsets. But by being the inverse to , that pre-image function is equal to , regarded as a function on subsets:

Hence sends opens to opens precisely if does, which is the case precisely if is an open map, by definition. This shows the equivalence of the first two items. The equivalence between the first and the third follows similarly via prop. .

Now we consider some actual examples of homeomorphisms:

Example

(concrete point homeomorphic to abstract point space)

Let be a non-empty topological space, and let be any point. Regard the corresponding singleton subset as equipped with its subspace topology (example ). Then this is homeomorphic (def. ) to the abstract point space from example :

Example

(open interval homeomorphic to the real line)

Regard the real line as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) with its metric topology (example ).

Then the open interval (def. ) regarded with its subspace topology (example ) is homeomorphic (def.) to all of the real line

An inverse pair of continuous functions is for instance given (via example ) by

and

But there are many other choices for and that yield a homeomorphism.

Similarly, for all

-

the open intervals (example ) equipped with their subspace topology are all homeomorphic to each other,

-

the closed intervals are all homeomorphic to each other,

-

the half-open intervals of the form are all homeomorphic to each other;

-

the half-open intervals of the form are all homeomorphic to each other.

Generally, every open ball in (def. ) is homeomorphic to all of :

While mostly the interest in a given homeomorphism is in it being non-obvious from the definitions, many homeomorphisms that appear in practice exhibit “obvious re-identifications” for which it is of interest to leave them consistently implicit:

Example

(homeomorphisms between iterated product spaces)

Let , and be topological spaces.

Then:

-

There is an evident homeomorphism between the two ways of bracketing the three factors when forming their product topological space (def. ), called the associator:

-

There are evident homeomorphism between and its product topological space (def. ) with the point space (example ), called the left and right unitors:

and

-

There is an evident homeomorphism between the results of the two orders in which to form their product topological spaces (def. ), called the braiding:

Moreover, all these homeomorphisms are compatible with each other, in that they make the following diagrams commute (recall remark ):

-

(triangle identity)

-

(hexagon identities)

and

-

(symmetry)

In the language of category theory (remark ), all this is summarized by saying that the the functorial construction of product topological spaces (example ) gives the category Top of topological spaces the structure of a monoidal category which moreover is symmetrically braided.

From this, a basic result of category theory, the MacLane coherence theorem, guarantees that there is no essential ambiguity re-backeting arbitrary iterations of the binary product topological space construction, as long as the above homeomorphisms are understood.

Accordingly, we may write

for iterated product topological spaces without putting parenthesis.

The following are a sequence of examples all of the form that an abstractly constructed topological space is homeomorphic to a certain subspace of a Euclidean space. These examples are going to be useful in further developments below, for example in the proof below of the Heine-Borel theorem (prop. ).

-

Products of intervals are homeomorphic to hypercubes (example ).

-

The closed interval glued at its endpoints is homeomorphic to the circle (example ).

-

The cylinder, the Möbius strip and the torus are all homeomorphic to quotients of the square (example ).

Example

(product of closed intervals homeomorphic to hypercubes)

Let , and let for be closed intervals in the real line (example ), regarded as topological subspaces of the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) with its metric topology (example ). Then the product topological space (def. , example ) of all these intervals is homeomorphic (def. ) to the corresponding topological subspace of the -dimensional Euclidean space (example ):

Similarly for open intervals:

Proof

There is a canonical bijection between the underlying sets. It remains to see that this, as well and its inverse, are continuous functions. For this it is sufficient to see that under this bijection the defining basis (def. ) for the product topology is also a basis for the subspace topology. But this is immediate from lemma .

Example

(closed interval glued at endpoints homeomorphic circle)

As topological spaces, the closed interval (def. ) with its two endpoints identified is homeomorphic (def. ) to the standard circle:

More in detail: let

be the unit circle in the plane

equipped with the subspace topology (example ) of the plane , which is itself equipped with its standard metric topology (example ).

Moreover, let

be the quotient topological space (example ) obtained from the interval with its subspace topology by applying the equivalence relation which identifies the two endpoints (and nothing else).

Consider then the function

given by

This has the property that , so that it descends to the quotient topological space

We claim that is a homeomorphism (definition ).

First of all it is immediate that is a continuous function. This follows immediately from the fact that is a continuous function and by definition of the quotient topology (example ).

So we need to check that has a continuous inverse function. Clearly the restriction of itself to the open interval has a continuous inverse. It fails to have a continuous inverse on and on and fails to have an inverse at all on [0,1], due to the fact that . But the relation quotiented out in is exactly such as to fix this failure.

Example

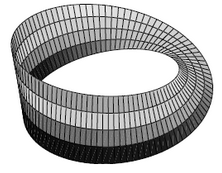

(cylinder, Möbius strip and torus homeomorphic to quotients of the square)

The square with two of its sides identified is the cylinder, and with also the other two sides identified is the torus:

If the sides are identified with opposite orientation, the result is the Möbius strip:

graphics grabbed from Lawson 03

Example

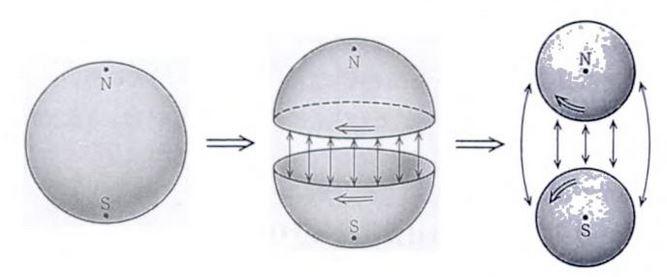

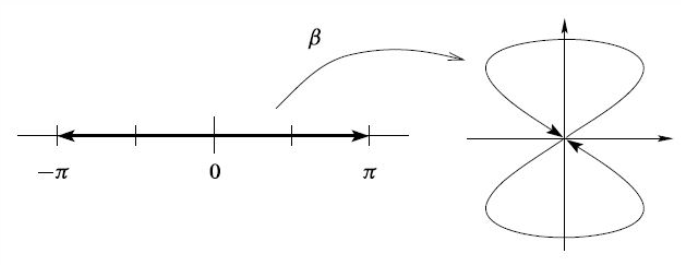

For then there is a homeomorphism (def. ) between the n-sphere (example ) with one point removed and the -dimensional Euclidean space (example ) with its metric topology (example ):

This homeomorphism is given by “stereographic projection”: One thinks of both the -sphere as well as the Euclidean space as topological subspaces (example ) of in the standard way (example ), such that they intersect in the equator of the -sphere. For one of the corresponding poles, then the homeomorphism is the function which sends a point along the line connecting it with to the point where this line intersects the equatorial plane.

In the canonical ambient coordinates this stereographic projection is given as follows:

Proof

First consider more generally the stereographic projection

of the entire ambient space minus the point onto the equatorial plane, still given by mapping a point to the unique point on the equatorial hyperplane such that the points , any sit on the same straight line.

This condition means that there exists such that

Since the only condition on is that this implies that

This equation has a unique solution for given by

and hence it follow that

Since rational functions are continuous (example ), this function is continuous and since the topology on is the subspace topology under the canonical embedding it follows that the restriction

is itself a continuous function (because its pre-images are the restrictions of the pre-images of to ).

To see that is a bijection of the underlying sets we need to show that for every

there is a unique satisfying

-

, hence

-

;

-

;

-

-

.

The last condition uniquely fixes the in terms of the given and the remaining , as

With this, the second condition says that

hence equivalently that

By the quadratic formula the solutions of this equation are

The solution violates the first condition above, while the solution satisfies it.

Therefore we have a unique solution, given by

In particular therefore also an inverse function to the stereographic projection exists and is a rational function, hence continuous by example . So we have exhibited a homeomorphism as required.

Important examples of pairs of spaces that are not homeomorphic include the following:

Theorem

(topological invariance of dimension)

For but , then the Euclidean spaces and (example , example ) are not homeomorphic.

More generally, an open subset in is never homeomorphic to an open subset in if .

The proofs of theorem are not elementary, in contrast to how obvious the statement seems to be intuitively. One approach is to use tools from algebraic topology: One assigns topological invariants to topological spaces, notably classes in ordinary cohomology or in topological K-theory), quantities that are invariant under homeomorphism, and then shows that these classes coincide for and for precisely only if .

One indication that topological invariance of dimension is not an elementary consequence of the axioms of topological spaces is that a related “intuitively obvious” statement is in fact false: One might think that there is no surjective continuous function if . But there are: these are called the Peano curves.

Separation axioms

The plain definition of topological space (above) happens to admit examples where distinct points or distinct subsets of the underlying set appear as more-or-less unseparable as seen by the topology on that set.

The extreme class of examples of topological spaces in which the open subsets do not distinguish distinct underlying points, or in fact any distinct subsets, are the codiscrete spaces (example ). This does occur in practice:

Example

(real numbers quotiented by rational numbers)

Consider the real line regarded as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) with its metric topology (example ) and consider the equivalence relation on which identifies two real numbers if they differ by a rational number:

Then the quotient topological space (def. )

is a codiscrete topological space (def. ), hence its topology does not distinguish any distinct proper subsets.

Here are some less extreme examples:

Example

(open neighbourhoods in the Sierpinski space)

Consider the Sierpinski space from example , whose underlying set consists of two points , and whose open subsets form the set . This means that the only (open) neighbourhood of the point is the entire space. Incidentally, also the topological closure of (def. ) is the entire space.

Example

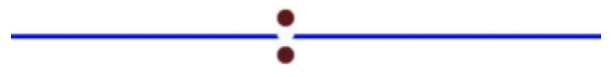

Consider the disjoint union space (example ) of two copies of the real line regarded as the 1-dimensional Euclidean space (example ) with its metric topology (example ), which is equivalently the product topological space (example ) of with the discrete topological space on the 2-element set (example ):

Moreover, consider the equivalence relation on the underlying set which identifies every point in the th copy of with the corresponding point in the other, the th copy, except when :

The quotient topological space by this equivalence relation (def. )

is called the line with two origins. These “two origins” are the points and .

We claim that in this space every neighbourhood of intersects every neighbourhood of .

Because, by definition of the quotient space topology, the open neighbourhoods of are precisely those that contain subsets of the form

But this means that the “two origins” and may not be separated by neighbourhoods, since the intersection of with is always non-empty:

In many applications one wants to exclude at least some such exotic examples of topological spaces from the discussion and instead concentrate on those examples for which the topology recognizes the separation of distinct points, or of more general disjoint subsets. The relevant conditions to be imposed on top of the plain axioms of a topological space are hence known as separation axioms which we discuss in the following.

These axioms are all of the form of saying that two subsets (of certain kinds) in the topological space are ‘separated’ from each other in one sense if they are ‘separated’ in a (generally) weaker sense. For example the weakest axiom (called ) demands that if two points are distinct as elements of the underlying set of points, then there exists at least one open subset that contains one but not the other.

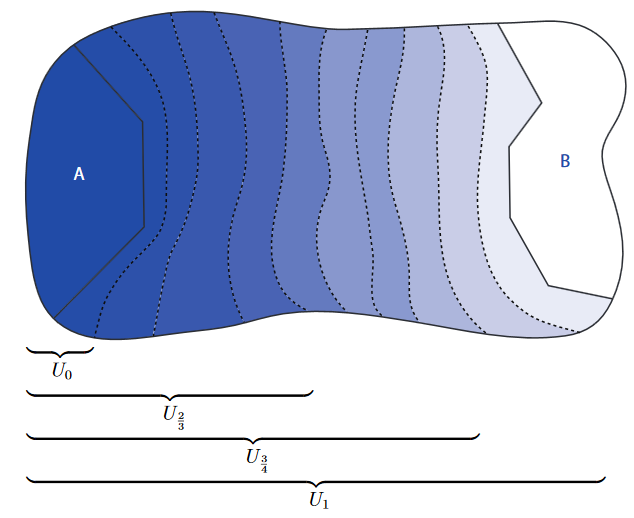

In this fashion one may impose a hierarchy of stronger axioms. For example demanding that given two distinct points, then each of them is contained in some open subset not containing the other () or that such a pair of open subsets around two distinct points may in addition be chosen to be disjoint (). Below in Tn-spaces we discuss the following hierarchy:

the main separation axioms

| number | name | statement | reformulation |

|---|---|---|---|