nLab geometry of physics -- perturbative quantum field theory

These notes (pdf, 323 pages) mean to give an expository but rigorous introduction to the basic concepts of relativistic perturbative quantum field theories, specifically those that arise as the perturbative quantization of Lagrangian field theories – such as quantum electrodynamics, quantum chromodynamics, and perturbative quantum gravity appearing in the standard model of particle physics.

This is one chapter of geometry of physics.

Previous chapters: smooth sets, supergeometry.

Contents

For broad introduction of the idea of the topic of perturbative quantum field theory see there and see

- PhysicsForums-Insights: Introduction to Perturbative Quantum Field Theory

Here, first we consider classical field theory (or rather pre-quantum field theory), complete with BV-BRST formalism; then its deformation quantization via causal perturbation theory to perturbative quantum field theory. This mathematically rigorous (i.e. clear and precise) formulation of the traditional informal lore has come to be known as perturbative algebraic quantum field theory.

We aim to give a fully local discussion, where all structures arise on the “jet bundle over the field bundle” (introduced below) and “transgress” from there to the spaces of field histories over spacetime (discussed further below). This “Higher Prequantum Geometry” streamlines traditional constructions and serves the conceptualization in the theory. This is joint work with Igor Khavkine.

In full beauty these concepts are extremely general and powerful; but the aim here is to give a first precise idea of the subject, not a fully general account. Therefore we concentrate on the special case where spacetime is Minkowski spacetime (def. below), where the field bundle (def. below) is an ordinary trivial vector bundle (example below) and hence the Lagrangian density (def. below) is globally defined. Similarly, when considering gauge theory we consider just the special case that the gauge parameter-bundle is a trivial vector bundle and we concentrate on the case that the gauge symmetries are “closed irreducible” (def. below). But we aim to organize all concepts such that the structure of their generalization to curved spacetime and non-trivial field bundles is immediate.

This comparatively simple setup already subsumes what is considered in traditional texts on the subject; it captures the established perturbative BRST-BV quantization of gauge fields coupled to fermions on curved spacetimes – which is the state of the art. Further generalization, necessary for the discussion of global topological effects, such as instanton configurations of gauge fields, will be discussed elsewhere (see at homotopical algebraic quantum field theory).

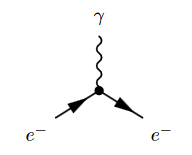

Alongside the theory we develop the concrete examples of the real scalar field, the electromagnetic field and the Dirac field; eventually combining these to a disussion of quantum electrodynamics.

running examples

| field | field bundle | Lagrangian density | equation of motion |

|---|---|---|---|

| real scalar field | expl. | expl. | expl. |

| Dirac field | expl. | expl. | expl. |

| electromagnetic field | expl. | expl. | expl. |

| Yang-Mills field | expl. , expl. | expl. | expl. |

| B-field | expl. | expl | expl. |

| field | Poisson bracket | causal propagator | Wightman propagator | Feynman propagator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| real scalar field | expl. , expl. | prop. | def. | def. |

| Dirac field | expl. , expl. | prop. | def. | def. |

| electromagnetic field | prop. | prop. |

| field | gauge symmetry | local BRST complex | gauge fixing |

|---|---|---|---|

| electromagnetic field | expl. | expl. | expl. |

| Yang-Mills field | expl. | expl. | … |

| B-field | expl. | expl. | … |

| interacting field theory | interaction Lagrangian density | interaction Wick algebra-element |

|---|---|---|

| phi^n theory | exp. | expl. |

| quantum electrodynamics | expl. | expl. |

References

Pointers to the literature are given in each chapter, alongside the text. The following is a selection of these references.

The discussion of spinors in chapter 2. Spacetime follows Baez-Huerta 09.

The functorial geometry of supergeometric spaces of field histories in 3. Fields follows Schreiber 13, further developed by Giotopoulos & Sati 2023.

For the jet bundle-formulation of variational calculus of Lagrangian field theory in 4. Field variations, and 5. Lagrangians we follow Anderson 89 and Olver 86, further developed by Giotopoulos & Sati 2023; for 6. Symmetries augmented by Fiorenza-Rogers-Schreiber 13b.

The identification of polynomial observables with distributions in 7. Observables was observed by Paugam 12.

The discussion of the Peierls-Poisson bracket in 8. Phase space is based on Khavkine 14.

The derivation of wave front sets of propagators in 9. Propagators takes clues from Radzikowski 96 and uses results from Gelfand-Shilov 66.

For the general idea of BV-BRST formalism a good review is Henneaux 90.

The Lie algebroid-perspective on BRST complexes developed in chapter 10. Gauge symmetries, may be compared to Barnich 10.

For the local BV-BRST theory laid out in chapter 11. Reduced phase space we are following Barnich-Brandt-Henneaux 00.

For the BV-gauge fixing developed in 12. Gauge fixing we take clues from Fredenhagen-Rejzner 11a.

For the free quantum BV-operators in 13. Free quantum fields and the interacting quantum master equation in 15. Interacting quantum fields we are following Fredenhagen-Rejzner 11b, Rejzner 11, which in turn is taking clues from Hollands 07.

The discussion of quantization in 13. Quantization takes clues from Hawkins 04, Collini 16 and spells out the derivation of the Moyal star product from geometric quantization of symplectic groupoids due to Gracia-Bondia & Varilly 94.

The perspective on the Wick algebra in 14. Free quantum fields goes back to Dito 90 and was revived for pAQFT in Dütsch-Fredenhagen 00. The proof of the folklore result that the perturbative Hadamard vacuum state on the Wick algebra is indeed a state is cited from Dütsch 18.

The discussion of causal perturbation theory in 15. Interacting quantum fields follows the original Epstein-Glaser 73. The relevance here of the star product induced by the Feynman propagator was highlighted in Fredenhagen-Rejzner 12. The proof that the interacting field algebra of observables defined by Bogoliubov's formula is a causally local net in the sense of the Haag-Kastler axioms is that of Brunetti-Fredenhagen 00.

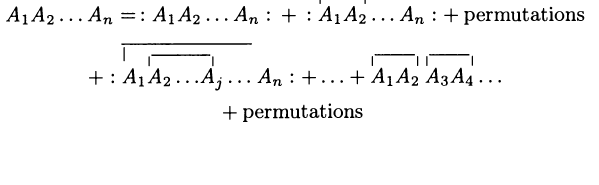

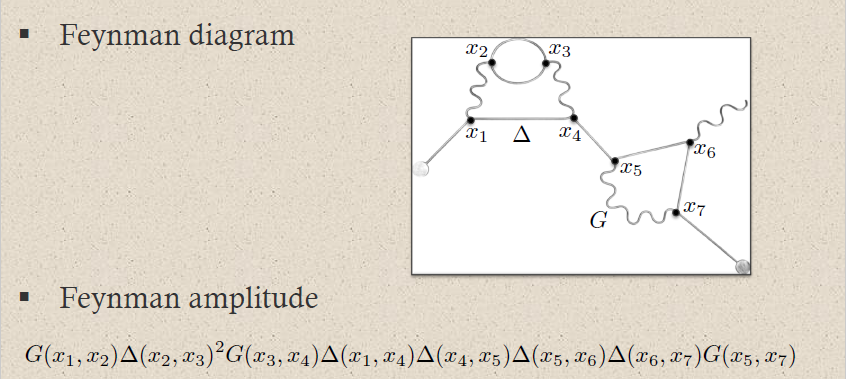

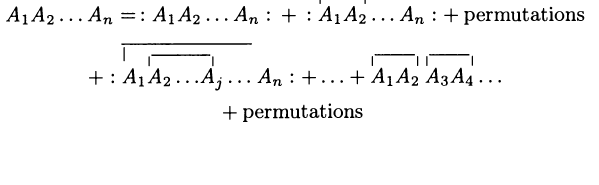

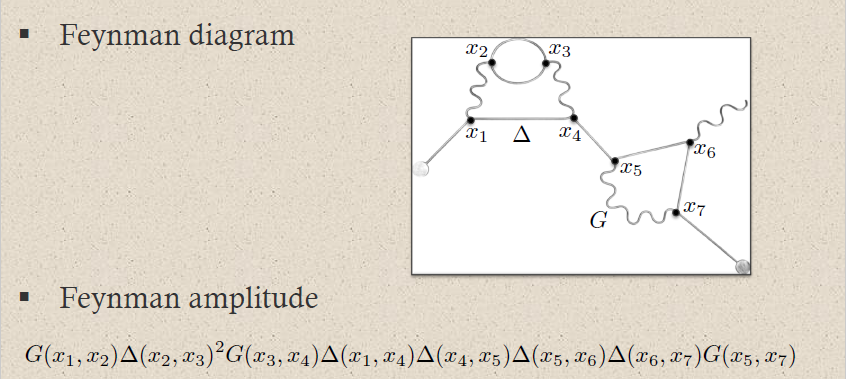

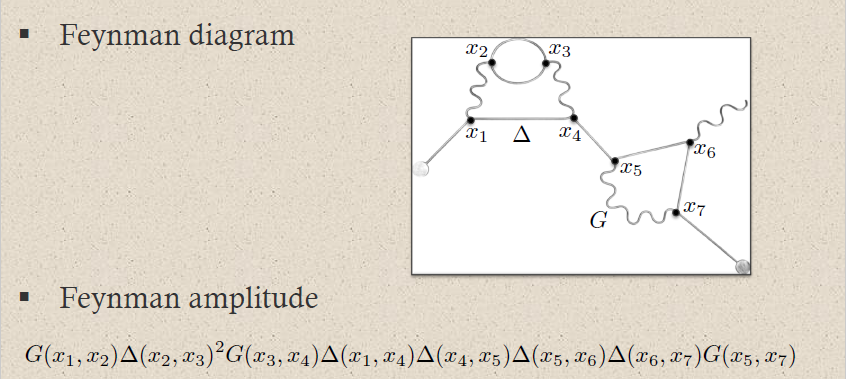

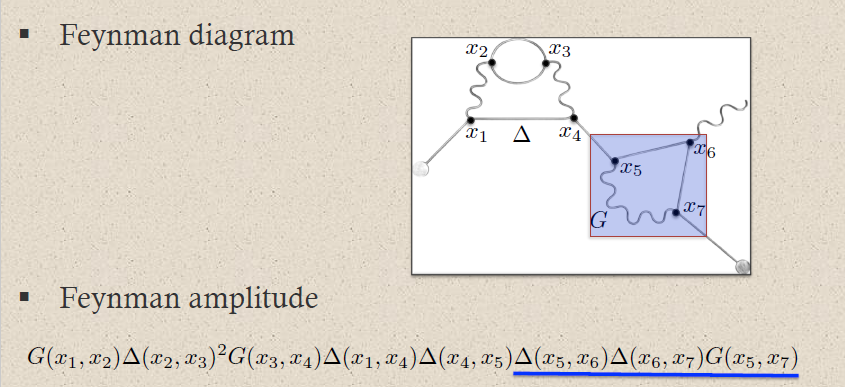

Our derivation of Feynman diagrammatics follows Keller 10, chapter IV, our derivation of the quantum master equation follows Rejzner 11, section 5.1.3, and our discussion of Ward identities is informed by Dütsch 18, chapter 4.

In chapter 16. Renormalization we take from Brunetti-Fredenhagen 00 the perspective of Epstein-Glaser renormalization via extension of distributions and from Brunetti-Dütsch-Fredenhagen 09 and Dütsch 10 the rigorous formulation of Gell-Mann Low renormalization group flow, UV-regularization, effective quantum field theory and Polchinski's flow equation.

Acknowledgement

These notes profited greatly from discussions with Igor Khavkine and Michael Dütsch.

Thanks also to Marco Benini, Klaus Fredenhagen, Arnold Neumaier and Kasia Rejzner for helpful discussion.

Geometry

The geometry of physics is differential geometry. This is the flavor of geometry which is modeled on Cartesian spaces with smooth functions between them. Here we briefly review the basics of differential geometry on Cartesian spaces.

In principle the only background assumed of the reader here is

-

usual naive set theory (e.g. Lawvere-Rosebrugh 03);

-

the concept of the continuum: the real line , the plane , etc.

-

the concepts of differentiation and integration of functions on such Cartesian spaces;

hence essentially the content of multi-variable differential calculus.

We now discuss:

As we uncover Lagrangian field theory further below, we discover ever more general concepts of “space” in differential geometry, such as smooth manifolds, diffeological spaces, infinitesimal neighbourhoods, supermanifolds, Lie algebroids and super Lie ∞-algebroids. We introduce these incrementally as we go along:

more general spaces in differential geometry introduced further below

| higher differential geometry | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| differential geometry | smooth manifolds (def. ) | diffeological spaces (def. ) | smooth sets (def. ) | formal smooth sets (def. ) | super formal smooth sets (def. ) | super formal smooth ∞-groupoids (not needed in fully perturbative QFT) | |||||

| infinitesimal geometry, Lie theory | infinitesimally thickened points (def. ) | superpoints (def. ) | Lie ∞-algebroids (def. ) | ||||||||

| higher Lie theory | |||||||||||

| needed in QFT for: | spacetime (def. ) | space of field histories (def. ) | Cauchy surface (def. ), perturbation theory (def. ) | Dirac field (expl. ), Pauli exclusion principle | infinitesimal gauge symmetry/BRST complex (expl. ) |

Abstract coordinate systems

What characterizes differential geometry is that it models geometry on the continuum, namely the real line , together with its Cartesian products , regarded with its canonical smooth structure (def. below). We may think of these Cartesian spaces as the “abstract coordinate systems” and of the smooth functions between them as the “abstract coordinate transformations”.

We will eventually consider below much more general “smooth spaces” than just the Cartesian spaces ; but all of them are going to be understood by “laying out abstract coordinate systems” inside them, in the general sense of having smooth functions mapping a Cartesian space smoothly into them. All structure on generalized smooth spaces is thereby reduced to compatible systems of structures on just Cartesian spaces, one for each smooth “probe” . This is called “functorial geometry”.

Notice that the popular concept of a smooth manifold (def./prop. below) is essentially that of a smooth space which locally looks just like a Cartesian space, in that there exist sufficiently many which are (open) isomorphisms onto their images. Historically it was a long process to arrive at the insight that it is wrong to fix such local coordinate identifications , or to have any structure depend on such a choice. But it is useful to go one step further:

In functorial geometry we do not even focus attention on those that are isomorphisms onto their image, but consider all “probes” of by “abstract coordinate systems”. This makes differential geometry both simpler as well as more powerful. The analogous insight for algebraic geometry is due to Grothendieck 65; it was transported to differential geometry by Lawvere 67.

This allows to combine the best of two superficially disjoint worlds: On the one hand we may reduce all constructions and computations to coordinates, the way traditionally done in the physics literature; on the other hand we have full conceptual control over the coordinate-free generalized spaces analyzed thereby. What makes this work is that all coordinate-constructions are functorially considered over all abstract coordinate systems.

Definition

(Cartesian spaces and smooth functions between them)

For we say that the set of n-tuples of real numbers is a Cartesian space. This comes with the canonical coordinate functions

which send an n-tuple of real numbers to the th element in the tuple, for .

For

any function between Cartesian spaces, we may ask whether its partial derivative along the th coordinate exists, denoted

If this exists, we may in turn ask that the partial derivative of the partial derivative exists

and so on.

A general higher partial derivative obtained this way is, if it exists, indexed by an n-tuple of natural numbers and denoted

where is the total order of the partial derivative.

If all partial derivative to all orders of a function exist, then is called a smooth function.

Of course the composition of two smooth functions is again a smooth function.

The inclined reader may notice that this means that Cartesian spaces with smooth functions between them constitute a category (“CartSp”); but the reader not so inclined may ignore this.

For the following it is useful to think of each Cartesian space as an abstract coordinate system. We will be dealing with various generalized smooth spaces (see the table below), but they will all be characterized by a prescription for how to smoothly map abstract coordinate systems into them.

Example

(coordinate functions are smooth functions)

Given a Cartesian space , then all its coordinate functions (def. )

are smooth functions (def. ).

For

any smooth function and write

. for its composition with this coordinate function.

Example

(algebra of smooth functions on Cartesian spaces)

For each , the set

of real number-valued smooth functions on the -dimensional Cartesian space (def. ) becomes a commutative associative algebra over the ring of real numbers by pointwise addition and multiplication in : for and

-

.

The inclusion

is given by the constant functions.

We call this the real algebra of smooth functions on :

If

is any smooth function (def. ) then pre-composition with (“pullback of functions”)

is an algebra homomorphism. Moreover, this is clearly compatible with composition in that

Stated more abstractly, this means that assigning algebras of smooth functions is a functor

from the category CartSp of Cartesian spaces and smooth functions between them (def. ), to the opposite of the category Alg of -algebras.

Definition

(local diffeomorphisms and open embeddings of Cartesian spaces)

A smooth function from one Cartesian space to itself (def. ) is called a local diffeomorphism, denoted

if the determinant of the matrix of partial derivatives (the “Jacobian” of ) is everywhere non-vanishing

If the function is both a local diffeomorphism, as above, as well as an injective function then we call it an open embedding, denoted

Definition

(good open cover of Cartesian spaces)

For a Cartesian space (def. ), a differentiably good open cover is

-

an indexed set

of open embeddings (def. )

such that the images

satisfy:

-

(open cover) every point of is contained in at least one of the ;

-

(good) all finite intersections are either empty set or themselves images of open embeddings according to def. .

The inclined reader may notice that the concept of differentiably good open covers from def. is a coverage on the category CartSp of Cartesian spaces with smooth functions between them, making it a site, but the reader not so inclined may ignore this.

(Fiorenza-Schreiber-Stasheff 12, def. 6.3.9)

Given any context of objects and morphisms between them, such as the Cartesian spaces and smooth functions from def. it is of interest to fix one object and consider other objects parameterized over it. These are called bundles (def. ) below. For reference, we briefly discuss here the basic concepts related to bundles in the context of Cartesian spaces.

Of course the theory of bundles is mostly trivial over Cartesian spaces; it gains its main interest from its generalization to more general smooth manifolds (def./prop. below). It is still worthwhile for our development to first consider the relevant concepts in this simple case first.

For more exposition see at fiber bundles in physics.

Definition

(bundles)

We say that a smooth function (def. ) is a bundle just to amplify that we think of it as exhibiting as being a “space over ”:

For a point, we say that the fiber of this bundle over is the pre-image

of the point under the smooth function. We think of as exhibiting a “smoothly varying” set of fiber spaces over .

Given two bundles and over , a homomorphism of bundles between them is a smooth function (def. ) between their total spaces which respects the bundle projections, in that

Hence a bundle homomorphism is a smooth function that sends fibers to fibers over the same point:

The inclined reader may notice that this defines a category of bundles over , which is in fact just the slice category ; the reader not so inclined may ignore this.

Definition

(sections)

Given a bundle (def. ) a section is a smooth function such that

This means that sends every point to an element in the fiber over that point

We write

for the set of sections of a bundle.

For and two bundles and for

a bundle homomorphism between them (def. ), then composition with sends sections to sections and hence yields a function denoted

Example

For and Cartesian spaces, then the Cartesian product equipped with the projection

to is a bundle (def. ), called the trivial bundle with fiber . This represents the constant smoothly varying set of fibers, constant on

If is the point, then this is the identity bundle

Given any bundle , then a bundle homomorphism (def. ) from the identity bundle to is equivalently a section of (def. )

Definition

A bundle (def. ) is called a fiber bundle with typical fiber if there exists a differentiably good open cover (def. ) such that the restriction of to each is isomorphic to the trivial fiber bundle with fiber over . Such diffeomorphisms are called local trivializations of the fiber bundle:

Definition

A vector bundle is a fiber bundle (def. ) with typical fiber a vector space such that there exists a local trivialization whose gluing functions

for all are linear functions over each point .

A homomorphism of vector bundle is a bundle morphism (def. ) such that there exist local trivializations on both sides with respect to which is fiber-wise a linear map.

The inclined reader may notice that this makes vector bundles over a category (denoted ); the reader not so inclined may ignore this.

Example

(module of sections of a vector bundle)

Given a vector bundle (def. ), then its set of sections (def. ) becomes a real vector space by fiber-wise multiplication with real numbers. Moreover, it becomes a module over the algebra of smooth functions (example ) by the same fiber-wise multiplication:

For and two vector bundles and

a vector bundle homomorphism (def. ) then the induced function on sections (def. )

is compatible with this action by smooth functions and hence constitutes a homomorphism of -modules.

The inclined reader may notice that this means that taking spaces of sections yields a functor

from the category of vector bundles over to that over modules over .

Example

(tangent vector fields and tangent bundle)

For a Cartesian space (def. ) the trivial vector bundle (example , def. )

is called the tangent bundle of . With the coordinate functions on (def. ) we write for the corresponding linear basis of regarded as a vector space. Then a general section (def. )

of the tangent bundle has a unique expansion of the form

where a sum over indices is understood (Einstein summation convention) and where the components are smooth functions on (def. ).

Such a is also called a smooth tangent vector field on .

Each tangent vector field on determines a partial derivative on smooth functions

By the product law of differentiation, this is a derivation on the algebra of smooth functions (example ) in that

-

it is an -linear map in that

-

it satisfies the Leibniz rule

for all and all .

Hence regarding tangent vector fields as partial derivatives constitutes a linear function

from the space of sections of the tangent bundle. In fact this is a homomorphism of -modules (example ), in that for and we have

Example

Let be a fiber bundle. Then its vertical tangent bundle is the fiber bundle (def. ) over whose fiber over a point is the tangent bundle (def. ) of the fiber of over that point:

If is a trivial fiber bundle with fiber , then its vertical vector bundle is the trivial fiber bundle with fiber .

Definition

For a vector bundle (def. ), its dual vector bundle is the vector bundle whose fiber (2) over is the dual vector space of the corresponding fiber of :

The defining pairing of dual vector spaces applied pointwise induces a pairing on the modules of sections (def. ) of the original vector bundle and its dual with values in the smooth functions (def. ):

synthetic differential geometry

Below we encounter generalizations of ordinary differential geometry that include explicit “infinitesimals” in the guise of infinitesimally thickened points, as well as “super-graded infinitesimals”, in the guise of superpoints (necessary for the description of fermion fields such as the Dirac field). As we discuss below, these structures are naturally incorporated into differential geometry in just the same way as Grothendieck introduced them into algebraic geometry (in the guise of “formal schemes”), namely in terms of formally dual rings of functions with nilpotent ideals. That this also works well for differential geometry rests on the following three basic but important properties, which say that smooth functions behave “more algebraically” than their definition might superficially suggest:

Proposition

(the three magic algebraic properties of differential geometry)

-

embedding of Cartesian spaces into formal duals of R-algebras

For and two Cartesian spaces, the smooth functions between them (def. ) are in natural bijection with their induced algebra homomorphisms (example ), so that one may equivalently handle Cartesian spaces entirely via their -algebras of smooth functions.

Stated more abstractly, this means equivalently that the functor that sends a smooth manifold to its -algebra of smooth functions (example ) is a fully faithful functor:

(Kolar-Slovak-Michor 93, lemma 35.8, corollaries 35.9, 35.10)

-

embedding of smooth vector bundles into formal duals of R-algebra modules

For and two vector bundle (def. ) there is then a natural bijection between vector bundle homomorphisms and the homomorphisms of modules that these induces between the spaces of sections (example ).

More abstractly this means that the functor is a fully faithful functor

Moreover, the modules over the -algebra of smooth functions on which arise this way as sections of smooth vector bundles over a Cartesian space are precisely the finitely generated free modules over .

-

vector fields are derivations of smooth functions.

For a Cartesian space (example ), then any derivation on the -algebra of smooth functions (example ) is given by differentiation with respect to a uniquely defined smooth tangent vector field: The function that regards tangent vector fields with derivations from example

is in fact an isomorphism.

(This follows directly from the Hadamard lemma.)

Actually all three statements in prop. hold not just for Cartesian spaces, but generally for smooth manifolds (def./prop. below; if only we generalize in the second statement from free modules to projective modules. However for our development here it is useful to first focus on just Cartesian spaces and then bootstrap the theory of smooth manifolds and much more from that, which we do below.

We introduce and discuss differential forms on Cartesian spaces.

Definition

(differential 1-forms on Cartesian spaces and the cotangent bundle)

For a smooth differential 1-form on a Cartesian space (def. ) is an n-tuple

of smooth functions (def. ), which we think of equivalently as the coefficients of a formal linear combination

on a set of cardinality .

Here a sum over repeated indices is tacitly understood (Einstein summation convention).

Write

for the set of smooth differential 1-forms on .

We may think of the expressions as a linear basis for the dual vector space . With this the differential 1-forms are equivalently the sections (def. ) of the trivial vector bundle (example , def. )

called the cotangent bundle of (def. ):

This amplifies via example that has the structure of a module over the algebra of smooth functions , by the evident multiplication of differential 1-forms with smooth functions:

-

The set of differential 1-forms in a Cartesian space (def. ) is naturally an abelian group with addition given by componentwise addition

-

The abelian group is naturally equipped with the structure of a module over the algebra of smooth functions (example ), where the action is given by componentwise multiplication

Accordingly there is a canonical pairing between differential 1-forms and tangent vector fields (example )

With differential 1-forms in hand, we may collect all the first-order partial derivatives of a smooth function into a single object: the exterior derivative or de Rham differential is the -linear function

Under the above pairing with tangent vector fields this yields the particular partial derivative along :

We think of as a measure for infinitesimal displacements along the -coordinate of a Cartesian space. If we have a measure of infintesimal displacement on some and a smooth function , then this induces a measure for infinitesimal displacement on by sending whatever happens there first with to and then applying the given measure there. This is captured by the following definition:

Definition

(pullback of differential 1-forms)

For a smooth function, the pullback of differential 1-forms along is the function

between sets of differential 1-forms, def. , which is defined on basis-elements by

and then extended linearly by

This is compatible with identity morphisms and composition in that

Stated more abstractly, this just means that pullback of differential 1-forms makes the assignment of sets of differential 1-forms to Cartesian spaces a contravariant functor

The following definition captures the idea that if is a measure for displacement along the -coordinate, and a measure for displacement along the coordinate, then there should be a way to get a measure, to be called , for infinitesimal surfaces (squares) in the --plane. And this should keep track of the orientation of these squares, with

being the same infinitesimal measure with orientation reversed.

Definition

(exterior algebra of differential n-forms)

For , the smooth differential forms on a Cartesian space (def. ) is the exterior algebra

over the algebra of smooth functions (example ) of the module of smooth 1-forms.

We write for the sub-module of degree and call its elements the differential n-forms.

Explicitly this means that a differential n-form on is a formal linear combination over (example ) of basis elements of the form for :

Now all the constructions for differential 1-forms above extent naturally to differential n-forms:

Definition

(exterior derivative or de Rham differential)

For a Cartesian space (def. ) the de Rham differential (5) uniquely extended as a derivation of degree +1 to the exterior algebra of differential forms (def. )

meaning that for then

In components this simply means that

Since partial derivatives commute with each other, while differential 1-form anti-commute, this implies that is nilpotent

We say hence that differential forms form a cochain complex, the de Rham complex .

Definition

(contraction of differential n-forms with tangent vector fields)

The pairing of tangent vector fields with differential 1-forms (4) uniquely extends to the exterior algebra of differential forms (def. ) as a derivation of degree -1

In particular for two differential 1-forms, then

Proposition

(pullback of differential n-forms)

For a smooth function between Cartesian spaces (def. ) the operationf of pullback of differential 1-forms of def. extends as an -algebra homomorphism to the exterior algebra of differential forms (def. ),

given on basis elements by

This commutes with the de Rham differential on both sides (def. ) in that

hence that pullback of differential forms is a chain map of de Rham complexes.

This is still compatible with identity morphisms and composition in that

Stated more abstractly, this just means that pullback of differential n-forms makes the assignment of sets of differential n-forms to Cartesian spaces a contravariant functor

Proposition

Let be a Cartesian space (def. ), and let be a smooth tangent vector field (example ).

For write for the flow by diffeomorphisms along of parameter length .

Then the derivative with respect to of the pullback of differential forms along , hence the Lie derivative , is given by the anticommutator of the contraction derivation (def. ) with the de Rham differential (def. ):

Finally we turn to the concept of integration of differential forms (def. below). First we need to say what it is that differential forms may be integrated over:

Definition

(smooth singular simplicial chains in Cartesian spaces)

For , the standard n-simplex in the Cartesian space (def. ) is the subset

More generally, a smooth singular n-simplex in a Cartesian space is a smooth function (def. )

to be thought of as a smooth extension of its restriction

(This is called a singular simplex because there is no condition that be an embedding in any way, in particular may be a constant function.)

A singular chain in of dimension is a formal linear combination of singular -simplices in .

In particular, given a singular -simplex , then its boundary is a singular chain of singular -simplices .

Definition

(fiber-integration of differential forms) over smooth singular chains in Cartesian spaces)

For and a differential n-form (def. ), which may be written as

then its integration over the standard n-simplex (def. ) is the ordinary integral (e.g. Riemann integral)

More generally, for

in any Cartesian space . Then the integration of over is the sum of the integrations, as above, of the pullback of differential forms (def. ) along all the singular n-simplices in the chain:

Finally, for another Cartesian space, then fiber integration of differential forms along is the linear map

which on differential forms of the form with ( pulled back from and from ) is given by:

Proposition

(Stokes theorem for fiber-integration of differential forms)

For a smooth singular simplicial chain (def. ) the operation of fiber-integration of differential forms along (def. ) is compatible with the exterior derivative on (def. ) in that

where is the de Rham differential on (def. ) and where the second equality is the Stokes theorem along :

This concludes our review of the basics of (synthetic) differential geometry on which the following development of quantum field theory is based. In the next chapter we consider spacetime and spin.

Spacetime

Relativistic field theory takes place on spacetime.

The concept of spacetime makes sense for every dimension with . The observable universe has macroscopic dimension , but quantum field theory generally makes sense also in lower and in higher dimensions. For instance quantum field theory in dimension 0+1 is the “worldline” theory of particles, also known as quantum mechanics; while quantum field theory in dimension may be “KK-compactified” to an “effective” field theory in dimension which generally looks more complicated than its higher dimensional incarnation.

However, every realistic field theory, and also most of the non-realistic field theories of interest, contain spinor fields such as the Dirac field (example below) and the precise nature and behaviour of spinors does depend sensitively on spacetime dimension. In fact the theory of relativistic spinors is mathematically most natural in just the following four spacetime dimensions:

In the literature one finds these four dimensions advertized for two superficially unrelated reasons:

-

in precisely these dimensions “GS-superstrings” exist (see there).

However, both these explanations have a common origin in something simpler and deeper: Spacetime in these dimensions appears from the “Pauli matrices” with entries in the real normed division algebras. (In fact it goes deeper still, but this will not concern us here.)

This we explain now, and then we use this to obtain a slick handle on spinors in these dimensions, using simple linear algebra over the four real normed division algebras. At the end (in remark ) we give a dictionary that expresses these constructions in terms of the “two-component spinor notation” that is traditionally used in physics texts (remark below).

The relation between real spin representations and division algebras, is originally due to Kugo-Townsend 82, Sudbery 84 and others. We follow the streamlined discussion in Baez-Huerta 09 and Baez-Huerta 10.

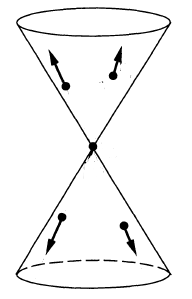

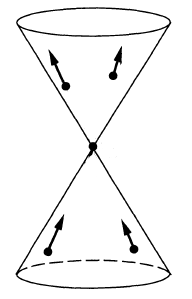

A key extra structure that the spinors impose on the underlying Cartesian space of spacetime is its causal structure, which determines which points in spacetime (“events”) are in the future or the past of other points (def. below). This causal structure will turn out to tightly control the quantum field theory on spacetime in terms of the “causal additivity of the S-matrix” (prop. below) and the induced “causal locality” of the algebra of quantum observables (prop. below). To prepare the discussion of these constructions, we end this chapter with some basics on the causal structure of Minkowski spacetime.

Real division algebras

To amplify the following pattern and to fix our notation for algebra generators, recall these definitions:

Definition

The complex numbers is the commutative algebra over the real numbers which is generated from one generators subject to the relation

- .

Definition

The quaternions is the associative algebra over the real numbers which is generated from three generators subject to the relations

-

for all

-

for a cyclic permutation of then

(graphics grabbed from Baez 02)

Definition

The octonions is the nonassociative algebra over the real numbers which is generated from seven generators subject to the relations

-

for all

-

for an edge or circle in the diagram shown (a labeled version of the Fano plane) then

and all relations obtained by cyclic permutation of the indices in these equations.

(graphics grabbed from Baez 02)

One defines the following operations on these real algebras:

Definition

(conjugation, real part, imaginary part and absolute value)

For , let

be the antihomomorphism of real algebras

given on the generators of def. , def. and def. by

This operation makes into a star algebra. For the complex numbers this is called complex conjugation, and in general we call it conjugation.

Let then

be the function

(“real part”) and

be the function

(“imaginary part”).

It follows that for all then the product of a with its conjugate is in the real center of

and we write the square root of this expression as

called the norm or absolute value function

This norm operation clearly satisfies the following properties (for all )

-

;

-

;

and hence makes a normed algebra.

Since is a division algebra, these relations immediately imply that each is a division algebra, in that

Hence the conjugation operation makes a real normed division algebra.

Remark

(sequence of inclusions of real normed division algebras)

Suitably embedding the sets of generators in def. , def. and def. into each other yields sequences of real star-algebra inclusions

For example for the first two inclusions we may send each generator to the generator of the same name, and for the last inclusion me may choose

Proposition

(Hurwitz theorem: , , and are the normed real division algebras)

The four algebras of real numbers , complex numbers , quaternions and octonions from def. , def. and def. respectively, which are real normed division algebras via def. , are, up to isomorphism, the only real normed division algebras that exist.

Remark

(Cayley-Dickson construction and sedenions)

While prop. says that the sequence from remark

is maximal in the category of real normed non-associative division algebras, there is a pattern that does continue if one disregards the division algebra property. Namely each step in this sequence is given by a construction called forming the Cayley-Dickson double algebra. This continues to an unbounded sequence of real nonassociative star-algebras

where the next algebra is called the sedenions.

What actually matters for the following relation of the real normed division algebras to real spin representations is that they are also alternative algebras:

Definition

Given any non-associative algebra , then the trilinear map

given on any elements by

is called the associator (in analogy with the commutator ).

If the associator is completely antisymmetric (in that for any permutation of three elements then for the signature of the permutation) then is called an alternative algebra.

If the characteristic of the ground field is different from 2, then alternativity is readily seen to be equivalent to the conditions that for all then

We record some basic properties of associators in alternative star-algebras that we need below:

Proposition

(properties of alternative star algebras)

Let be an alternative algebra (def. ) which is also a star algebra. Then (using def. ):

-

the associator vanishes when at least one argument is real

-

the associator changes sign when one of its arguments is conjugated

-

the associator vanishes when one of its arguments is the conjugate of another

-

the associator is purely imaginary

Proof

That the associator vanishes as soon as one argument is real is just the linearity of an algebra product over the ground ring.

Hence in fact

This implies the second statement by linearity. And so follows the third statement by skew-symmetry:

The fourth statement finally follows by this computation:

Here the first equation follows by inspection and using that , the second follows from the first statement above, and the third is the anti-symmetry of the associator.

It is immediate to check that:

Proposition

(, , and are real alternative algebras)

The real algebras of real numbers, complex numbers, def. ,quaternions def. and octonions def. are alternative algebras (def. ).

Proof

Since the real numbers, complex numbers and quaternions are associative algebras, their associator vanishes identically. It only remains to see that the associator of the octonions is skew-symmetric. By linearity it is sufficient to check this on generators. So let be a circle or a cyclic permutation of an edge in the Fano plane. Then by definition of the octonion multiplication we have

and similarly

The analog of the Hurwitz theorem (prop. ) is now this:

Proposition

(, , and are precisely the alternative real division algebras)

The only division algebras over the real numbers which are also alternative algebras (def. ) are the real numbers themselves, the complex numbers, the quaternions and the octonions from prop. .

This is due to (Zorn 30).

For the following, the key point of alternative algebras is this equivalent characterization:

Proposition

(alternative algebra detected on subalgebras spanned by any two elements)

A nonassociative algebra is alternative, def. , precisely if the subalgebra generated by any two elements is an associative algebra.

This is due to Emil Artin, see for instance (Schafer 95, p. 18).

Proposition is what allows to carry over a minimum of linear algebra also to the octonions such as to yield a representation of the Clifford algebra on . This happens in the proof of prop. below.

So we will be looking at a fragment of linear algebra over these four normed division algebras. To that end, fix the following notation and terminology:

Definition

(hermitian matrices with values in real normed division algebras)

Let be one of the four real normed division algebras from prop. , hence equivalently one of the four real alternative division algebras from prop. .

Say that an matrix with coefficients in

is a hermitian matrix if the transpose matrix equals the componentwise conjugated matrix (def. ):

Hence with the notation

we have that is a hermitian matrix precisely if

We write for the real vector space of hermitian matrices.

Definition

(trace reversal)

Let be a hermitian matrix as in def. . Its trace reversal is the result of subtracting its trace times the identity matrix:

Minkowski spacetime in dimensions 3,4,6 and 10

We now discover Minkowski spacetime of dimension 3,4,6 and 10, in terms of the real normed division algebras from prop. , equivalently the real alternative division algebras from prop. : this is prop./def. and def. below.

Proposition/Definition

(Minkowski spacetime as real vector space of hermitian matrices in real normed division algebras)

Let be one of the four real normed division algebras from prop. , hence one of the four real alternative division algebras from prop. .

Then the real vector space of hermitian matrices over (def. ) equipped with the inner product whose quadratic form is the negative of the determinant operation on matrices is Minkowski spacetime:

hence

-

for ;

-

for ;

-

for ;

-

for .

Here we think of the vector space on the left as with

equipped with the canonical coordinates labeled .

As a linear map the identification is given by

This means that the quadratic form is given on an element by

By the polarization identity the quadratic form induces a bilinear form

given by

This is called the Minkowski metric.

Finally, under the above identification the operation of trace reversal from def. corresponds to time reversal in that

Proof

We need to check that under the given identification, the Minkowski norm-square is indeed given by minus the determinant on the corresponding hermitian matrices. This follows from the nature of the conjugation operation from def. :

Remark

(physical units of length)

As the term “metric” suggests, in application to physics, the Minkowski metric in prop./def. is regarded as a measure of length: for a tangent vector at a point in Minkowski spacetime, interpreted as a displacement from event to event , then

-

if then

is interpreted as a measure for the spatial distance between and ;

-

if then

is interpreted as a measure for the time distance between and .

But for this to make physical sense, an operational prescription needs to be specified that tells the experimentor how the real number is to be translated into an physical distance between actual events in the observable universe.

Such an operational prescription is called a physical unit of length. For example “centimeter” is a physical unit of length, another one is “femtometer” .

The combined information of a real number and a physical unit of length such as meter, jointly written

is a prescription for finding actual distance in the observable universe. Alternatively

is another prescription, that translates the same real number into another physical distance.

But of course they are related, since physical units form a torsor over the group of non-negative real numbers, meaning that any two are related by a unique rescaling. For example

with .

This means that once any one prescription of turning real numbers into spacetime distances is specified, then any other such prescription is obtained from this by rescaling these real numbers. For example

The point to notice here is that, via the last line, we may think of this as rescaling the metric from to .

In quantum field theory physical units of length are typically expressed in terms of a physical unit of “action”, called “Planck's constant” , via the combination of units called the Compton wavelength

parameterized, in turn, by a physical unit of mass . For the mass of the electron, the Compton wavelength is

Another physical unit of length parameterized by a mass is the Schwarzschild radius , where is the gravitational constant. Solving the equation

for yields the Planck mass

The corresponding Compton wavelength is given by the Planck length

Definition

(Minkowski spacetime as a pseudo-Riemannian Cartesian space)

Prop./def. introduces Minkowski spacetime for as a a vector space equipped with a norm . The genuine spacetime corresponding to this is this vector space regaded as a Cartesian space, i.e. with smooth functions (instead of just linear maps) to it and from it (def. ). This still carries one copy of over each point , as its tangent space (example )

and the Cartesian space equipped with the Lorentzian inner product from prop./def. on each tangent space (a “pseudo-Riemannian Cartesian space”) is Minkowski spacetime as such.

We write

for the canonical volume form on Minkowski spacetime.

We use the Einstein summation convention: Expressions with repeated indices indicate summation over the range of indices.

For example a differential 1-form on Minkowski spacetime may be expanded as

Moreover we use square brackets around indices to indicate skew-symmetrization. For example a differential 2-form on Minkowski spacetime may be expanded as

The identification of Minkowski spacetime (def. ) in the exceptional dimensions with the generalized Pauli matrices (prop./def. ) has some immediate useful implications:

Proposition

(Minkowski metric in terms of trace reversal)

In terms of the trace reversal operation from def. , the determinant operation on hermitian matrices (def. ) has the following alternative expression

and the Minkowski inner product from prop. has the alternative expression

Proposition

(special linear group acts by linear isometries on Minkowski spacetime )

For one of the four real normed division algebras (prop. ) the special linear group acts on Minkowski spacetime in dimension (def. ) by linear isometries given under the identification with the Pauli matrices in prop./def. by conjugation:

Proof

For this is immediate from matrix calculus, but we spell it out now. While the argument does not directly apply to the case of the octonions, one can check that it still goes through, too.

First we need to see that the action is well defined. This follows from the associativity of matrix multiplication and the fact that forming conjugate transpose matrices is an antihomomorphism: . In particular this implies that the action indeed sends hermitian matrices to hermitian matrices:

By prop./def. such an action is an isometry precisely if it preserves the determinant. This follows from the multiplicative property of determinants: and their compativility with conjugate transposition: , and finally by the assumption that is an element of the special linear group, hence that its determinant is :

In fact the special linear groups of linear isometries in prop. are the spin groups (def. below) in these dimensions.

exceptional spinors and real normed division algebras

This we explain now.

Lorentz group and spin group

Definition

For , write

for the subgroup of the general linear group on those linear maps which preserve this bilinear form on Minkowski spacetime (def ), in that

This is the Lorentz group in dimension .

The elements in the Lorentz group in the image of the special orthogonal group are rotations in space. The further elements in the special Lorentz group , which mathematically are “hyperbolic rotations” in a space-time plane, are called boosts in physics.

One distinguishes the following further subgroups of the Lorentz group :

-

is the subgroup of elements which have determinant +1 (as elements of the general linear group);

-

the proper orthochronous (or restricted) Lorentz group

is the further subgroup of elements which preserve the time orientation of vectors in that .

Proposition

(connected component of Lorentz group)

As a smooth manifold, the Lorentz group (def. ) has four connected components. The connected component of the identity is the proper orthochronous Lorentz group (def. ). The other three components are

-

,

where, as matrices,

is the operation of point reflection at the origin in space, where

is the operation of reflection in time and hence where

is point reflection in spacetime.

The following concept of the Clifford algebra (def. ) of Minkowski spacetime encodes the structure of the inner product space in terms of algebraic operation (“geometric algebra”), such that the action of the Lorentz group becomes represented by a conjugation action (example below). In particular this means that every element of the proper orthochronous Lorentz group may be “split in half” to yield a double cover: the spin group (def. below).

Definition

For , we write

for the -graded associative algebra over which is generated from generators in odd degree (“Clifford generators”), subject to the relation

where is the inner product of Minkowski spacetime as in def. .

These relations say equivalently that

We write

for the antisymmetrized product of Clifford generators. In particular, if all the are pairwise distinct, then this is simply the plain product of generators

Finally, write

for the algebra anti-automorphism given by

Remark

(vectors inside Clifford algebra)

By construction, the vector space of linear combinations of the generators in a Clifford algebra (def. ) is canonically identified with Minkowski spacetime (def. )

via

hence via

such that the defining quadratic form on is identified with the anti-commutator in the Clifford algebra

where on the right we are, in turn, identifying with the linear span of the unit in .

The key point of the Clifford algebra (def. ) is that it realizes spacetime reflections, rotations and boosts via conjugation actions:

Example

(Clifford conjugation)

For and the Minkowski spacetime of def. , let be any vector, regarded as an element via remark .

Then

- the conjugation action of a single Clifford generator on sends to its

reflection at the hyperplane ;

-

sends to the result of rotating it in the -plane through an angle .

Proof

This is immediate by inspection:

For the first statement, observe that conjugating the Clifford generator with yields up to a sign, depending on whether or not:

Therefore for then is the result of multiplying the -component of by .

For the second statement, observe that

This is the canonical action of the Lorentzian special orthogonal Lie algebra . Hence

is the rotation action as claimed.

Remark

Since the reflections, rotations and boosts in example are given by conjugation actions, there is a crucial ambiguity in the Clifford elements that induce them:

-

the conjugation action by coincides precisely with the conjugation action by ;

-

the conjugation action by coincides precisely with the conjugation action by .

Definition

For , the spin group is the group of even graded elements of the Clifford algebra (def. ) which are unitary with respect to the conjugation operation from def. :

Proposition

The function

from the spin group (def. ) to the general linear group in -dimensions given by sending to the conjugation action

(via the identification of Minkowski spacetime as the subspace of the Clifford algebra containing the linear combinations of the generators, according to remark )

is

-

a group homomorphism onto the proper orthochronous Lorentz group (def. ):

-

exhibiting a -central extension.

Proof

That the function is a group homomorphism into the general linear group, hence that it acts by linear transformations on the generators follows by using that it clearly lands in automorphisms of the Clifford algebra.

That the function lands in the Lorentz group follows from remark :

That it moreover lands in the proper Lorentz group follows from observing (example ) that every reflection is given by the conjugation action by a linear combination of generators, which are excluded from the group (as that is defined to be in the even subalgebra).

To see that the homomorphism is surjective, use that all elements of are products of rotations in hyperplanes. If a hyperplane is spanned by the bivector , then such a rotation is given, via example by the conjugation action by

for some , hence is in the image.

That the kernel is is clear from the fact that the only even Clifford elements which commute with all vectors are the multiples of the identity. For these and hence the condition is equivalent to . It is clear that these two elements are in the center of . This kernel reflects the ambiguity from remark .

Spinors in dimensions 3, 4, 6 and 10

We now discuss how real spin representations (def. ) in spacetime dimensions 3,4, 6 and 10 are naturally induced from linear algebra over the four real alternative division algebras (prop. ).

Definition

(Clifford algebra via normed division algebra)

Let be one of the four real normed division algebras from prop. , hence one of the four real alternative division algebras from prop. .

Define a real linear map

from (the real vector space underlying) Minkowski spacetime to real linear maps on

Here on the right we are using the isomorphism from prop. for identifying a spacetime vector with a -matrix, and we are using the trace reversal from def. .

Remark

(Clifford multiplication via octonion-valued matrices)

Each operation of in def. is clearly a linear map, even for being the non-associative octonions. The only point to beware of is that for the octonions, then the composition of two such linear maps is not in general given by the usual matrix product.

Proposition

(real spin representations via normed division algebras)

The map in def. gives a representation of the Clifford algebra (this def.), i.e of

-

for ;

-

for ;

-

for ;

-

for .

Hence this Clifford representation induces representations of the spin group on the real vector spaces

and hence on

Proof

We need to check that the Clifford relation

is satisfied (where we used (11) and (8)). Now by definition, for any then

where on the right we have in each component ordinary matrix product expressions.

Now observe that both expressions on the right are sums of triple products that involve either one real factor or two factors that are conjugate to each other:

Since the associators of triple products that involve a real factor and those involving both an element and its conjugate vanish by prop. (hence ultimately by Artin’s theorem, prop. ). In conclusion all associators involved vanish, so that we may rebracket to obtain

Proposition

Let be one of the four real normed division algebras and the corresponding spin representation from prop. .

Then there are bilinear maps from two spinors (according to prop. ) to the real numbers

as well as to

given, respectively, by forming the real part (def. ) of the canonical -inner product

and by forming the product of a column vector with a row vector to produce a matrix, possibly up to trace reversal (def. ) under the identification from prop. :

and

For the -component of this map is

These pairings have the following properties

-

both are -equivalent;

-

the pairing is symmetric:

(12)

(Baez-Huerta 09, prop. 8, prop. 9).

Remark

(two-component spinor notation)

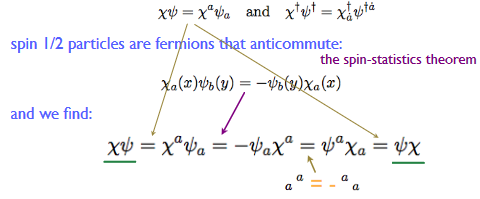

In the physics/QFT literature the expressions for spin representations given by prop. are traditionally written in two-component spinor notation as follows:

-

An element of is denoted and called a left handed spinor;

-

an element of is denoted and called a right handed spinor;

-

an element of is denoted

(13)and called a Dirac spinor;

and the Clifford action of prop. corresponds to the generalized “Pauli matrices”:

-

a hermitian matrix as in prop regarded as a linear map via def. is denoted

-

the negative of the trace-reversal (def. ) of such a hermitian matrix, regarded as a linear map , is denoted

-

the bilinear spinor-to-vector pairing from prop. is written as the matrix multiplication

where the Dirac conjugate on the left is given on by

(14)hence, with (13):

(15)

Finally, it is common to abbreviate contractions with the Clifford algebra generators by a slash, as in

or

This is called the Feynman slash notation.

(e.g. Dermisek I-8, Dermisek I-9)

Below we spell out the example of the Lagrangian field theory of the Dirac field in detail (example ). For discussion of massive chiral spinor fields one also needs the following, here we just mention this for completeness:

Proposition

(chiral spinor mass pairing)

In dimension 2+1 and 3+1, there exists a non-trivial skew-symmetric pairing

which may be normalized such that in the two-component spinor basis of remark we have

Proof

Take the non-vanishing components of to be

and

With this equation (17) is checked explicitly. It is clear that thus defined is skew symmetric as long as the component algebra is commutative, which is the case for being or .

Causal structure

We need to consider the following concepts and constructions related to the causal structure of Minkowski spacetime (def. ).

Definition

(spacelike, timelike, lightlike directions; past and future)

Given two points in Minkowski spacetime (def. ), write

for their difference, using the vector space structure underlying Minkowski spacetime.

Recall the Minkowski inner product on , given by prop./def. . Then via remark we say that the difference vector is

Definition

For a point in spacetime (an event), we write

for the subsets of events that are in the timelike future or in the timelike past of , respectively (def. ) called the open future cone and open past cone, respectively, and

for the subsets of events that are in the timelike or lightlike future or past, respectivel, called the closed future cone and closed past cone, respectively.

The union

of the closed future cone and past cone is called the full causal cone of the event . Its boundary is the light cone.

More generally for a subset of events we write

for the union of the future/past closed cones of all events in the subset.

Definition

(compactly sourced causal support)

Consider a vector bundle (def. ) over Minkowski spacetime (def. ).

Write for the spaces of smooth sections (def. ), and write

for the subsets on those smooth sections whose support is

-

() inside a compact subset,

-

() inside the closed future cone/closed past cone, respectively, of a compact subset,

-

() inside the closed causal cone of a compact subset, which equivalently means that the intersection with every (spacelike) Cauchy surface is compact (Sanders 13, theorem 2.2),

-

() inside the past of a Cauchy surface (Sanders 13, def. 3.2),

-

() inside the future of a Cauchy surface (Sanders 13, def. 3.2),

-

() inside the future of one Cauchy surface and the past of another (Sanders 13, def. 3.2).

(Bär 14, section 1, Khavkine 14, def. 2.1)

Definition

Consider the relation on the set of subsets of spacetime which says a subset is not prior to a subset , denoted , if does not intersect the causal past of (def. ), or equivalently that does not intersect the causal future of :

(Beware that this is just a relation, not an ordering, since it is not relation.)

If and we say that the two subsets are spacelike separated and write

Definition

(causal complement and causal closure of subset of spacetime)

For a subset of spacetime, its causal complement is the complement of the causal cone:

The causal complement of the causal complement is called the causal closure. If

then the subset is called a causally closed subset.

Given a spacetime , we write

for the partially ordered set of causally closed subsets, partially ordered by inclusion .

Definition

For a causally closed subset of spacetime (def. ) say that an adiabatic switching function or infrared cutoff function for is a smooth function of compact support (a bump function) whose restriction to some neighbourhood of is the constant function with value :

Often we consider the vector space space spanned by a formal variable (the coupling constant) under multiplication with smooth functions, and consider as adiabatic switching functions the corresponding images in this space,

which are thus bump functions constant over a neighbourhood of not on 1 but on the formal parameter :

In this sense we may think of the adiabatic switching as being the spacetime-depependent coupling “constant”.

The following lemma will be key in the derivation (proof of prop. below) of the causal locality of algebra of quantum observables in perturbative quantum field theory:

Lemma

(causal partition)

Let be a causally closed subset (def. ) and let be a compactly supported smooth function which vanishes on a neighbourhood , i.e. .

Then there exists a causal partition of in that there exist compactly supported smooth functions such that

-

they sum up to :

-

their support satisfies the following causal ordering (def. )

Proof idea

By assumption has a Cauchy surface. This may be extended to a Cauchy surface of , such that this is one leaf of a foliation of by Cauchy surfaces, given by a diffeomorphism with the original at zero. There exists then such that the restriction of to the interval is in the causal complement of the given region (def. ):

Let then be any smooth function with

-

.

Then

are smooth functions as required.

This concludes our discussion of spin and spacetime. In the next chapter we consider the concept of fields on spacetime.

Fields

In this chapter we discuss these topics:

A field history on a given spacetime (a history of spatial field configurations, see remark below) is a quantity assigned to each point of spacetime (each event), such that this assignment varies smoothly with spacetime points. For instance an electromagnetic field history (example below) is at each point of spacetime a collection of vectors that encode the direction in which a charged particle passing through that point would feel a force (the “Lorentz force”, see example below).

This is readily formalized (def. below): If denotes the smooth manifold of “values” that the given kind of field may take at any spacetime point, then a field history is modeled as a smooth function from spacetime to this space of values:

It will be useful to unify spacetime and the space of field values (the field fiber) into a single manifold, the Cartesian product

and to think of this equipped with the projection map onto the first factor as a fiber bundle of spaces of field values over spacetime

This is then called the field bundle, which specifies the kind of values that the given field species may take at any point of spacetime. Since the space of field values is the fiber of this fiber bundle (def. ), it is sometimes also called the field fiber. (See also at fiber bundles in physics.)

Given a field bundle , then a field history is a section of that bundle (def. ). The discussion of field theory concerns the space of all possible field histories, hence the space of sections of the field bundle (example below). This is a very “large” generalized smooth space, called a diffeological space (def. below).

Or rather, in the presence of fermion fields such as the Dirac field (example below), the Pauli exclusion principle demands that the field bundle is a super-manifold, and that the fermionic space of field histories (example below) is a super-geometric generalized smooth space: a super smooth set (def. below).

This smooth structure on the space of field histories will be crucial when we discuss observables of a field theory below, because these are smooth functions on the space of field histories. In particular it is this smooth structure which allows to derive that linear observables of a free field theory are given by distributions (prop. ) below. Among these are the point evaluation observables (delta distributions) which are traditionally denoted by the same symbol as the field histories themselves.

Hence there are these aspects of the concept of “field” in physics, which are closely related, but crucially different:

aspects of the concept of fields

| aspect | term | type | description | def. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| field component | , | coordinate function on jet bundle of field bundle | def. , def. | |

| field history | , | jet prolongation of section of field bundle | def. , def. | |

| field observable | , | derivatives of delta-functional on space of sections | def. , example | |

| averaging of field observable | observable-valued distribution | def. | ||

| algebra of quantum observables | non-commutative algebra structure on field observables | def. , def. |

Definition

(fields and field histories)

Given a spacetime , then a type of fields on is a smooth fiber bundle (def. )

called the field bundle,

Given a type of fields on this way, then a field history of that type on is a term of that type, hence is a smooth section (def. ) of this bundle, namely a smooth function of the form

such that composed with the projection map it is the identity function, i.e. such that

The set of such sections/field histories is to be denoted

Remark

(field histories are histories of spatial field configurations)

Given a section of the field bundle (def. ) and given a spacelike (def. ) submanifold (def. ) of spacetime in codimension 1, then the restriction of to may be thought of as a field configuration in space. As different spatial slices are chosen, one obtains such field configurations at different times. It is in this sense that the entirety of a section is a history of field configurations, hence a field history (def ).

Remark

(possible field histories)

After we give the set of field histories (18) differential geometric structure, below in example and example , we call it the space of field histories. This should be read as space of possible field histories; containing all field histories that qualify as being of the type specified by the field bundle .

After we obtain equations of motion below in def. , these serve as the “laws of nature” that field histories should obey, and they define the subspace of those field histories that do solve the equations of motion; this will be denoted

and called the on-shell space of field histories (41).

For the time being, not to get distracted from the basic idea of quantum field theory, we will focus on the following simple special case of field bundles:

Example

(trivial vector bundle as a field bundle)

In applications the field fiber is often a finite dimensional vector space. In this case the trivial field bundle with fiber is of course a trivial vector bundle (def. ).

Choosing any linear basis of the field fiber, then over Minkowski spacetime (def. ) we have canonical coordinates on the total space of the field bundle

where the index ranges from to , while the index ranges from 1 to .

If this trivial vector bundle is regarded as a field bundle according to def. , then a field history is equivalently an -tuple of real-valued smooth functions on spacetime:

Example

(field bundle for real scalar field)

If is a spacetime and if the field fiber

is simply the real line, then the corresponding trivial field bundle (def. )

is the trivial real line bundle (a special case of example ) and the corresponding field type (def. ) is called the real scalar field on . A configuration of this field is simply a smooth function on with values in the real numbers:

Example

(field bundle for electromagnetic field)

On Minkowski spacetime (def. ), let the field bundle (def. ) be given by the cotangent bundle

This is a trivial vector bundle (example ) with canonical field coordinates .

A section of this bundle, hence a field history, is a differential 1-form

on spacetime (def. ). Interpreted as a field history of the electromagnetic field on , this is often called the vector potential. Then the de Rham differential (def. ) of the vector potential is a differential 2-form

known as the Faraday tensor. In the canonical coordinate basis 2-forms this may be expanded as

Here are called the components of the electric field, while are called the components of the magnetic field.

Example

(field bundle for Yang-Mills field over Minkowski spacetime)

Let be a Lie algebra of finite dimension with linear basis , in terms of which the Lie bracket is given by

Over Minkowski spacetime (def. ), consider then the field bundle which is the cotangent bundle tensored with the Lie algebra

This is the trivial vector bundle (example ) with induced field coordinates

A section of this bundle is a Lie algebra-valued differential 1-form

with components

This is called a field history for Yang-Mills gauge theory (at least if is a semisimple Lie algebra, see example below).

For is the line Lie algebra, this reduces to the case of the electromagnetic field (example ).

For this is a field history for the gauge field of the strong nuclear force in quantum chromodynamics.

For readers familiar with the concepts of principal bundles and connections on a bundle we include the following example which generalizes the Yang-Mills field over Minkowski spacetime from example to the situation over general spacetimes.

Example

(general Yang-Mills field in fixed topological sector)

Let be any spacetime manifold and let be a compact Lie group with Lie algebra denoted . Let be a -principal bundle and a chosen connection on it, to be called the background -Yang-Mills field.

Then the field bundle (def. ) for -Yang-Mills theory in the topological sector is the tensor product of vector bundles

of the adjoint bundle of and the cotangent bundle of .

With the choice of , every (other) connection on uniquely decomposes as

where

is a section of the above field bundle, hence a Yang-Mills field history.

The electromagnetic field (def. ) and the Yang-Mills field (def. , def. ) with differential 1-forms as field histories are the basic examples of gauge fields (we consider this in more detail below in Gauge symmetries). There are also higher gauge fields with differential n-forms as field histories:

Example

(field bundle for B-field)

On Minkowski spacetime (def. ), let the field bundle (def. ) be given by the skew-symmetrized tensor product of vector bundles of the cotangent bundle with itself

This is a trivial vector bundle (example ) with canonical field coordinates subject to

A section of this bundle, hence a field history, is a differential 2-form (def. )

on spacetime.

Given any field bundle, we will eventually need to regard the set of all field histories as a “smooth set” itself, a smooth space of sections, to which constructions of differential geometry apply (such as for the discussion of observables and states below ). Notably we need to be talking about differential forms on .

However, a space of sections does not in general carry the structure of a smooth manifold; and it carries the correct smooth structure of an infinite dimensional manifold only if is a compact space (see at manifold structure of mapping spaces). Even if it does carry infinite dimensional manifold structure, inspection shows that this is more structure than actually needed for the discussion of field theory. Namely it turns out below that all we need to know is what counts as a smooth family of sections/field histories, hence which functions of sets

from any Cartesian space (def. ) into count as smooth functions, subject to some basic consistency condition on this choice.

This structure on is called the structure of a diffeological space:

Definition

A diffeological space is

-

for each a choice of subset

of the set of functions from the underlying set of to , to be called the smooth functions or plots from to ;

-

for each smooth function between Cartesian spaces (def. ) a choice of function

to be thought of as the precomposition operation

such that

-

(constant functions are smooth)

-

-

If is the identity function on , then is the identity function on the set of plots ;

-

If are two composable smooth functions between Cartesian spaces (def. ), then pullback of plots along them consecutively equals the pullback along the composition:

i.e.

-

-

(gluing)

If is a differentiably good open cover of a Cartesian space (def. ) then the function which restricts -plots of to a set of -plots

is a bijection onto the set of those tuples of plots, which are “matching families” in that they agree on intersections:

Finally, given and two diffeological spaces, then a smooth function between them

is

-

a function of the underlying sets

such that

-

for a plot of , then the composition is a plot of :

(Stated more abstractly, this says simply that diffeological spaces are the concrete sheaves on the site of Cartesian spaces from def. .)

For more background on diffeological spaces see also geometry of physics – smooth sets.

Example

(Cartesian spaces are diffeological spaces)

Let be a Cartesian space (def. ) Then it becomes a diffeological space (def. ) by declaring its plots to the ordinary smooth functions .

Under this identification, a function between the underlying sets of two Cartesian spaces is a smooth function in the ordinary sense precisely if it is a smooth function in the sense of diffeological spaces.

Stated more abstractly, this statement is an example of the Yoneda embedding over a subcanonical site.

More generally, the same construction makes every smooth manifold a smooth set.

Example

(diffeological space of field histories)

Let be a smooth field bundle (def. ). Then the set of field histories/sections (def. ) becomes a diffeological space (def. )

by declaring that a smooth family of field histories, parameterized over any Cartesian space is a smooth function out of the Cartesian product manifold of with

such that for each we have , i.e.

The following example is included only for readers who wonder how infinite-dimensional manifolds fit in. Since we will never actually use infinite-dimensional manifold-structure, this example is may be ignored.

Example

(Fréchet manifolds are diffeological spaces)

Consider the particular type of infinite-dimensional manifolds called Fréchet manifolds. Since ordinary smooth manifolds are an example, for a Fréchet manifold there is a concept of smooth functions . Hence we may give the structure of a diffeological space (def. ) by declaring the plots over to be these smooth functions , with the evident postcomposition action.

It turns out that then that for and two Fréchet manifolds, there is a natural bijection between the smooth functions between them regarded as Fréchet manifolds and [regarded as . Hence it does not matter which of the two perspectives we take (unless of course a more general than a enters the picture, at which point the second definition generalizes, whereas the first does not).]

Stated more abstractly, this means that Fréchet manifolds form a full subcategory of that of diffeological spaces (this prop.):

If is a compact smooth manifold and is a trivial fiber bundle with fiber a smooth manifold, then the set of sections carries a standard structure of a Fréchet manifold (see at manifold structure of mapping spaces). Under the above inclusion of Fréchet manifolds into diffeological spaces, this smooth structure agrees with that from example (see this prop.)

Once the step from smooth manifolds to diffeological spaces (def. ) is made, characterizing the smooth structure of the space entirely by how we may probe it by mapping smooth Cartesian spaces into it, it becomes clear that the underlying set of a diffeological space is not actually crucial to support the concept: The space is already entirely defined structurally by the system of smooth plots it has, and the underlying set is recovered from these as the set of plots from the point .

This is crucial for field theory: the spaces of field histories of fermionic fields (def. below) such as the Dirac field (example below) do not have underlying sets of points the way diffeological spaces have. Informally, the reason is that a point is a bosonic object, while and the nature of fermionic fields is the opposite of bosonic.